Salut D’amour, Liebesgruß or Love’s Greeting. Let’s see what we can learn from Sir Edward Elgar’s romantic short composition. Through analysing the arrangement, melodic construction and harmonic language, we will attempt to devise our own broader lessons from Elgar’s composition that we can take for ourselves as composers. These main lessons will be: how the melodic material we need might lie in the material we already have or come up with first. And how our opening sections are an inescapable foundation for our compositions. I suppose the other lesson we will learn, more pervasively is, how to write music to woo. It is nearly Valentine’s day, after all.

Analysis Video

Context

Salut D’amour is a composition for solo violin and piano, and it was composed in 1888. A piece of the late-19th century and composed in his early-30s, opus numbered 12, it is an earlier published composition of Elgar’s.

Dedicated to his fiancèe, Caroline Alice Roberts, the dedicatee name on the score, “Carice”, is her first and middle name, Caroline Alice, combined. Incidentally, Carice became the name of their first daughter.

Carice, or Caroline Alice, was fluent in German. For this reason, the original title, preserved by publishers as a subtitle, was Liebesgruß. This title was changed by publishers to the French translation Salut D’amour, presumably as they felt it would be more popular with their customers.

Useful links

Recording

Link to Score (IMSLP)

Arrangement

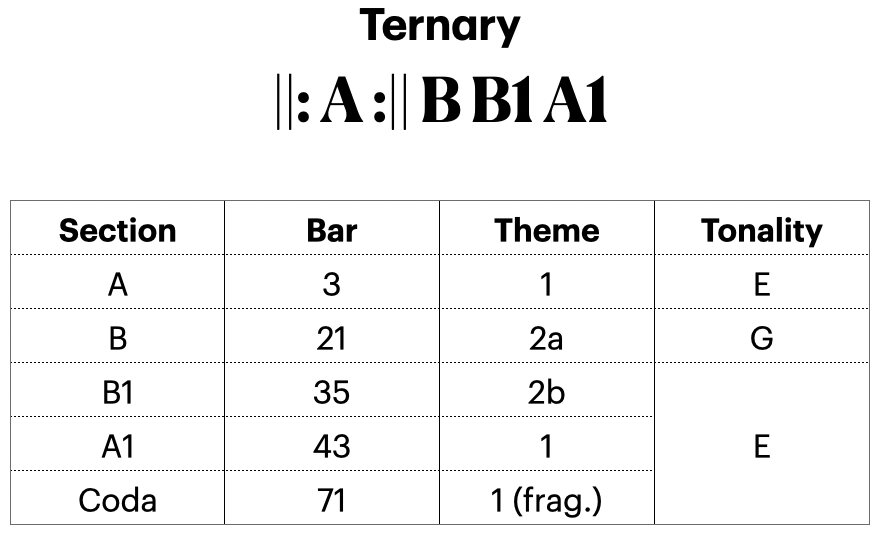

The composition, Salut D’amour, is in a ternary structure, where the outer sections use similar melodic material. These outer sections also, usually, share the same key. Particularly in the music of this period and earlier. Looking at the table (see below), we can see this is true of Elgar’s Salut D’amour:

- The outer sections are in E-major, while the middle section is in G-Major. (A chromatic mediant, the flattened 3rd scale degree, relationship with E-major.)

- The outer sections use the same melodic material, albeit slightly varied, while the middle section presents new melodic material.

However, regarding the melodic material, Elgar links the two themes of the A and B sections together, which we will look at in the next section.

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Melody

Theme 1 – Melodic Construction

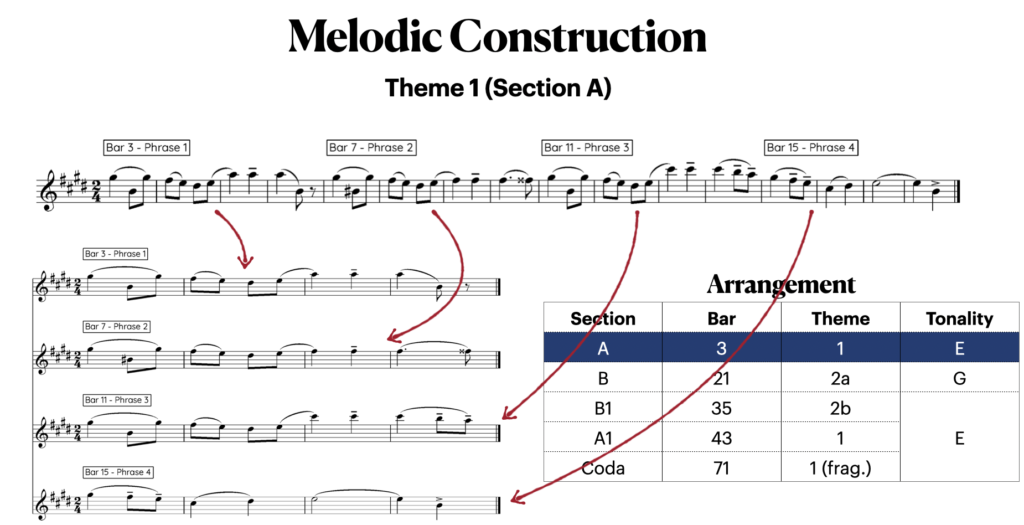

I am always amazed by Elgar’s concision when it comes to melody. He was remarkably economical in his control of melody and motif, and Salut D’amour demonstrates this in a shorter form composition.

(Below) I have extracted Theme 1 from Salut D’amour. I have also laid each of the phrases of Theme 1 out vertically. Similar to John Williams’ melodic construction in Fawkes the Phoenix (and Chopin in Nocturne No. 20!), we can see the first two bars of each of the first three phrases are alike. The only variation in these bars comes in bar 7, with the melodic-chromatic alteration to the note B to B#.

The fourth phrase’s first two bars are different to the other phrases, which is unsurprising for a melody. Often, in melodies like this, there is a phrase that breaks the repetitions or similarities of earlier phrases to complement them and round them off. However, despite these differences, we can still see faint similarities between phrase 4’s first bar and the other phrase’s first bars. Melodically the contour and intervals are different. Yet, Elgar preserves the melody rhythmically, using a crotchet, quaver and quaver rhythm.

Again, omitting phrase 4, we can see that the second two bars of each phrase (1- 3) are very similar again. Each using crotchets in their respective 3rd bars, Elgar alters where the melody goes each time. The repetitions of the earlier parts of each phrase, which we have looked at previously, create a form of anticipation, which Elgar leverages in bar 13, or the 3rd bar of phrase 3r, to elevate the melodic climax.

The final bar of phrase 3 leads into the 4th phrase, using the same crotchet, quaver, quaver rhythm as the opening motif of the melody, but the descending step melodic contour of bar 15. These are important links to the 2nd theme, which we will discuss next.

If you are enjoying this article, then you should consider subscribing to Any Old Music’s emailing list, to be notified when we release new and mailing list exclusive content (e.g. One Page Summaries and Creative Briefs etc.).

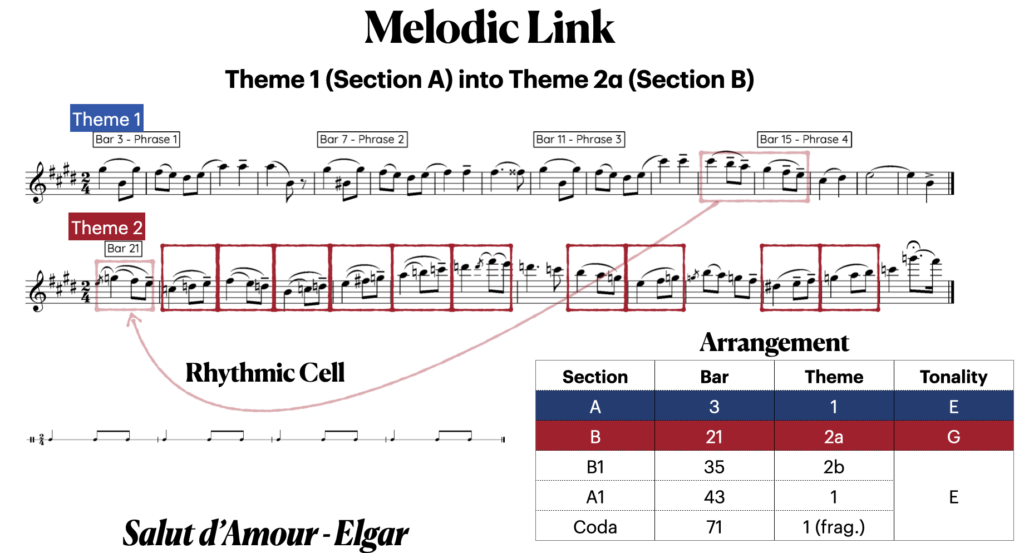

Theme 1 & 2 – Melodic Link

Looking at the melody of the B-section, which is in G-Major, we can immediately see Elgar’s economy at play again. Most of the bars contain the crotchet, quaver and quaver rhythmic cell mentioned in our analysis of the first theme. And more importantly, it appears in the form introduced at the close of theme 1.

Accentuating the link between the themes beyond the rhythm, Elgar introduces the stepwise motif at the end of theme 1. The stepwise, crotchet, quaver and quaver rhythm becomes a fundamental motif of theme 2.

Motivic in construction, the second theme comprises subtle permutations of this fundamental motif. Maintaining the stepwise motion and rhythm, Elgar alters the contour of each motif, weaving them into a longer melody that is both different, complementing theme 1, but also linked, giving us continuity.

The Lark Ascending (Music Composition Analysis) – Ralph Vaughan Williams (Article 1 – Lessons in Harmony)

How to repeat melodies without them getting boring… [Video]

5 ways of Understanding woodwinds

Arabesque No. 1 – Claude Debussy (Music Composition Analysis)

Spiegel im Spiegel – Arvo Pärt

Salut D’amour – Edward Elgar (Music Composition Technique Analysis)

Fawkes the Phoenix – John Williams (Music Composition Analysis – Arrangement, melody and melodic development)

Nocturne from Scénes de la Fôret – Mélanie Bonis

Troika from Lieutenant Kijé (suite) (1934) – Sergei Prokofiev

J. S. Bach – Badinerie (Orchestral Suite No. 2 in B-minor) (Bitesize Composition Analysis)

Ralph Vaughan Williams – Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus (Bitesize Orchestration Analysis)

This is Berk – How To Train Your Dragon (Dreamworks) – John Powell (Music Analysis – Composition Technique)

Harmony

Diatonic and Functional Harmony

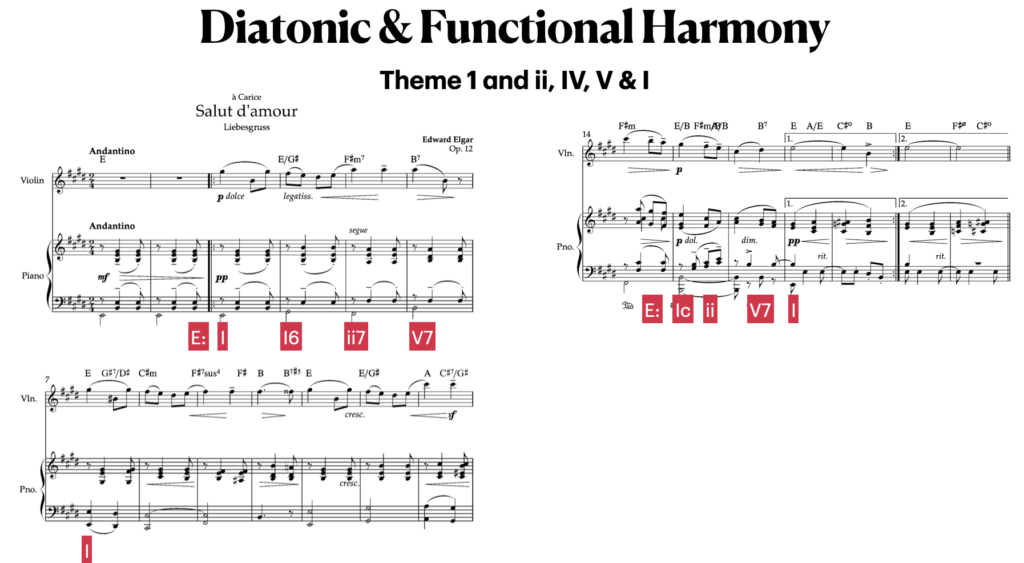

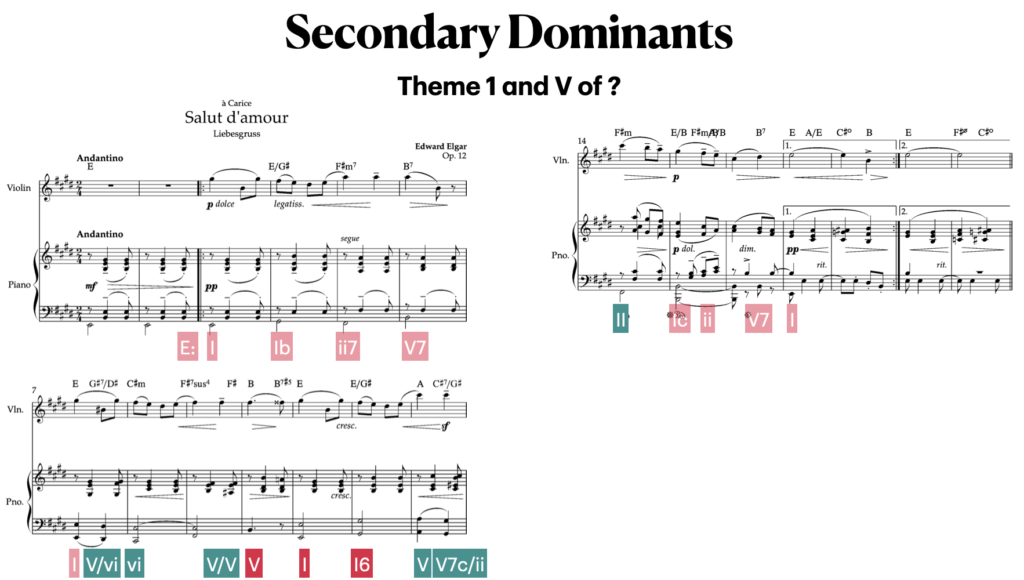

The harmony Elgar uses for Salut D’amour is largely diatonic, with some chromatic inflexions. The harmony is also very functional, with the application and explanation via Roman Numerals being straightforward. Looking more closely at the first theme of Salut D’amour, again, we can see the opening phrase utilises the stablest of stable progressions a homely I – I6 – ii7 – V7 – I. Nothing says home like an ii – V – I. The opening section of the music establishes E-major, and the use of diatonic, functional chords sets the tone of the short composition.

Secondary Dominants

One way in which Elgar inflects and brings chromatic harmonic colours into Salut D’amour is by using secondary dominants. Extending our analysis of this section further, Elgar uses some secondary dominants in bars 7, 9 and 13.

In bar 7, Elgar uses a V of vi. In other words, a major mediant chord in E-major, G#-major. This G#-major chord also happens to be the dominant of E-major’s relative minor, C#-minor, the chord used in bar 8.

Similarly, in bars 9 and 13, Elgar uses major chords for what would normally be minor triads in E-major, also having them lead onto their relative tonic chords. For example, from bar 9 into 10, we have F#-major (II) falling into B-major, the dominant (V) of E-major, and for bar 13 into 14, we have C#-major (VI) into F#-minor, the super-tonic of E-major. Typically, the super-tonic and sub-mediant of a major scale are minor. Elgar alters them, chromatically, to create secondary dominants.

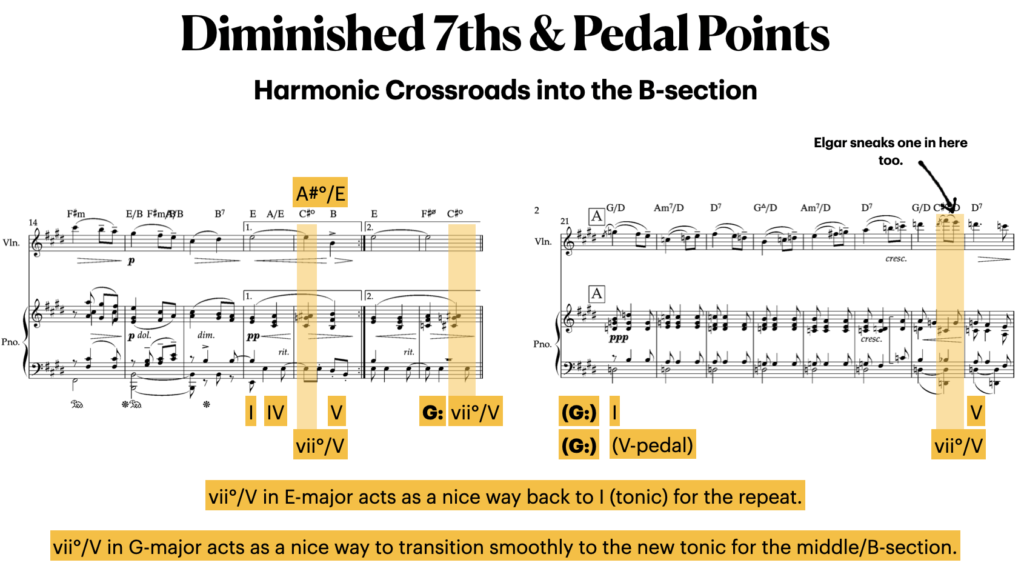

Leading-tone Diminished-7ths and Pedal-point

Another chromatic device that Elgar uses is the diminished-7th chord, which can be a functional acrobat. Limited in transposition, the same diminished chords appear similarly and enharmonically in several keys. Therefore, they can be the key link into a great many keys of varying distances.

Elgar, in this composition, Salut D’amour, uses them like secondary dominants. For example, in the 1st repeat section, at the end of section A, Elgar uses an A#° leading onto a B-major chord, which sets up a repetition starting in E-major.

Using the same diminished chord in the second repeat section, but this time as a C#°, the chord acts as a pivot into G-major, the key of the middle section.

Both chords act as vii°/V, first of E-major, leading onto a B-major chord, and then, secondly of G-major. However, rather than going to the dominant of G-major, a D-major chord, at bar 21, Elgar moves to a tonic G-major 6/4 or second inversion chord, keeping the bass note as a dominant pedal point, on the note D, for the next 8-bars.

Arvo Pärt – Für Alina (Bitesize Music Composition Analysis)

Bizet – Guiraud – Farandole from L’Arlesienne Suite No. 2 (Bitesize Composition Analysis)

Bernard Herrmann “The Merry-go-round” from “Walking Distance” (Bitesize Music Composition Analysis)

Aaron Copland – “Simple Gifts” (Appalachian Spring / Ballet for Martha) – Bitesize Music Composition Analysis

George Frideric Handel – Overture from Music for the Royal Fireworks – Bitesize Music Composition Analysis

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky – Symphony No. 2 “Little Russian” – Orchestrating Variety – Bitesize Orchestration Analysis

Frédéric Chopin – Nocturne No. 1 Op. 9 – Developing Melody – Bitesize Composition Analysis

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – K. 304, K. 448 & k. 550: varying repetitions – bitesize Composition analysis

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice – Paul Dukas (Music Composition Techniques Analysis)

Learning from John Williams – Recomposing Flag Parade

Le Papillon (from Chantefleurs et Chantefables) – Witold Lutosławski – Composition Technique

The Day the Earth Stood Still, Bernard Herrmann – Orchestration Technique

Close: Broader Lessons

Lest we get bogged down into harmonic theory, let’s think about broader lessons we can take from today’s analysis of Salut D’amour. For instance, the use of secondary dominant chords, diminished chords and how Elgar constructs and links melodies. What can we learn from Salut D’amour as composers?

Broader Harmony Lessons

A way in which we start a composition sets up everything we do subsequently. Elgar here clearly wants the harmonic language to be concise, but he also wants it to be pliable enough to allow the chromatic inflexions and the larger scale chromatic mediant modulation to G-major. To do this he is careful to inject secondary dominants, which keep the harmonic language functional but not a lead weight. Elgar is careful to set up a starting point that allows for some structural movement, without that movement being stark or surprising.

In essence, what I am saying is, the use of chords in the opening establishes the vocabulary of Elgar’s short story. Beyond tonality, this could be a more chromatic or atonal language. It could be modal, dissonant or consonant. This is not to say the music could not become more dissonant, if it starts consonant, more tonal, if it starts chromatic, atonal or modal. Rather, the introduction is the point from which we depart and what it does establishes the whole essence of the piece. In the case of Elgar, we have a rounded piece: we move away and return. However, in another composition it might be more linear. We might move away and never return. The piece could be a process of increasing dissonance or consonance. Fundamentally, though, we cannot escape the starting point, it is the listener’s point of reference and although we might not compose it first, the composition develops from it.

Broader Melody Lessons

The other lesson we can learn from Elgar is that, the building materials we need for our composition may well lie in the built materials we have. For example, the link we identified between Elgar’s two melodies for Salut D’amour. (I do not know how he made them.) One way could have been that he had two melodies, the opening and middle section, and to round off the opening melody he used a motif of the second. Another way is that he identified the motif that closed his opening melody and took that as the basis of his second melody. Or, he may well have identified the rhythmic quality of his opening motif and used that as an improvisatory anchor for composing the second melody. At this point, he might have then gone back, like with point one, and used the new stepwise motif as a means of rounding off the main melody.

It is difficult to say which is what and what is which. However, I do not think it matters to us here. The lesson we should take is that we may have the answers to our composition questions already. Assume we have a melody for a composition and we want to use it in a larger ternary structure, the answer could and maybe should lie in that melody.

If you have enjoyed this article, then you should consider subscribing to Any Old Music’s emailing list, to be notified when we release new and mailing list exclusive content (e.g. One Page Summaries and Creative Briefs etc.).