Spiegel im Spiegel – Arvo Pärt (analysis)

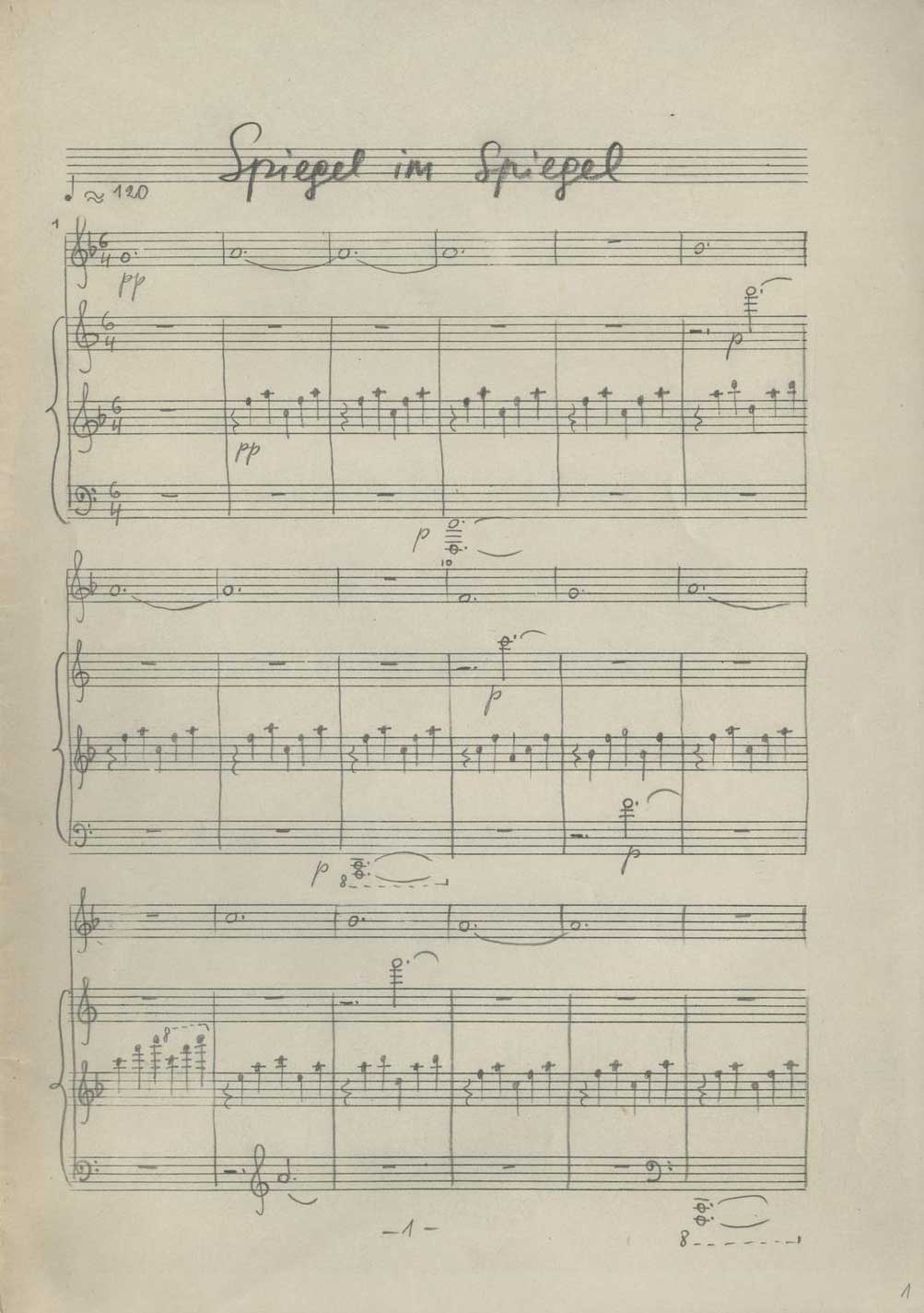

Spiegel im Spiegel is a composition by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt. The work was composed in 1978 for Violin and Piano. However, it exists in other combinations too, which typically include a solo instrument and piano. Today I want to break down this composition to see what we can learn from it as composers.

The title, Spiegel im Spiegel, is frequently translated into Mirror in the Mirror. Imagining the recursive, reflective imagery the title creates, the composition’s structures, which we will discuss, evoke a sense of infinitude. However, despite the infinite quality, Spiegel im Spiegel is tightly constrained.

Spiegel im Spiegel is one of Pärt’s early tintinnabuli compositions. Nevertheless, compared to Für Alina, he goes beyond tintinnabuli technique as we understand it from our analysis of Für Alina. For example, the use of a “voice” that boasts tintinnabuli qualities but differs from the standard tintinnabuli voice rules as we know them. Pärt also imposes additional constraints, different and similar to Für Alina.

It is somewhat poetic that a composition, such as Spiegel im Spiegel, a metaphor for endlessness or limitlessness, is so constrained. Today, we will investigate how Pärt creates a feeling of limitlessness or timelessness by using a range of limiting composition techniques.

Interested In Learning How To Compose Tintinnabuli? If so, I am currently offering the first chapter of my new tintinnabuli composition course for free here.

Score Video – Spiegel im Spiegel (1978) – Arvo Pärt

Recapping Tintinnabuli

Tintinnabuli, as a technique, deeply constrains the harmony and, in a sense, the counterpoint of a piece. (I’ll come back to what I mean by “in a sense” regarding counterpoint shortly. If you would like to learn more), I would recommend my article/video on Für Alina, where I afford more time to discuss tintinnabuli more generally and widely. However, I will recap it briefly here too.

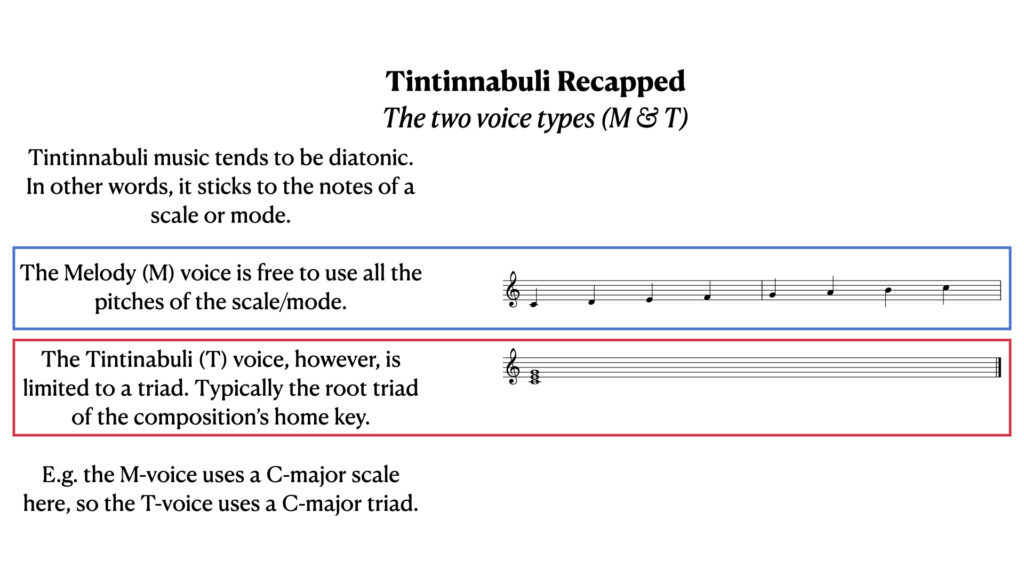

In brief, tintinnabuli music tends to be diatonic, only using pitches of a particular scale or mode. Moreover, there are usually two voice types: a melody, typically referred to as the M-voice, and a tintinnabuli, or T-voice. The M-voice has greater freedom to explore all the notes of the diatonic scale. The T-voice, on the other hand, is confined to a triad. Typically, this triad is on the tonic note of the scale or mode. The effect, therefore, is one of harmonic stasis, with tension and release––should it occur at all––occurring intervallic ally.

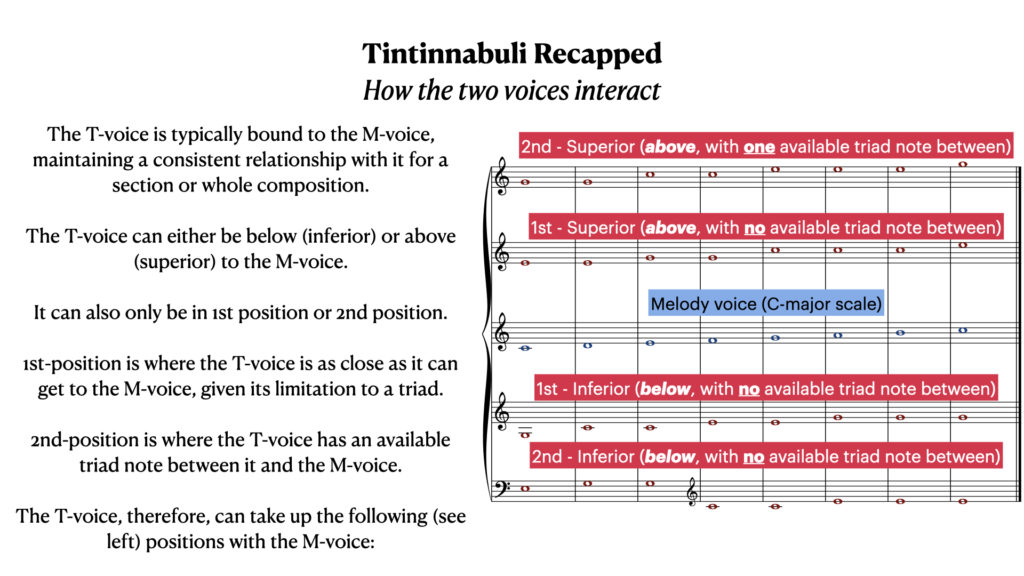

In tintinnabuli composition, the T-voice tends to be bound to the M-voice. The T-voice, limited to notes of the tonic triad, maintains a distinct and, typically, consistent relationship with the M-voice.

The relationships that the T and M-voice can share consist of two definitive parts:

- Whether the T-voice is above or below the M-voice.

- How close the T-voice is to the M-voice.

Regarding above and below, if the T-voice is higher, it is said to be in a superior position. If the T-voice is lower, then it is defined as inferior.

Regarding closeness, if the T-voice is on a triad note as close as it can get to the M-voice (remember, the T-voice is confined to the root triad!), it is said to be in a 1st position. If there is an available triad note between the T-voice and M-voice, then the T-voice is said to be in a 2nd position.

In combination, therefore, we can define the T-voice as being:

- 1st-Superior: above and as close to the M-voice as it can get.

- 2nd-Superior: above but with an available triad note between it and the M-voice.

- 1st-Inferior: below and as close to the M-voice as it can get.

- 2nd-Inferior: below but with an available triad note between it and the M-voice.

Taking a look at Spiegel im Spiegel’s use of the technique should elucidate it.

Interested In Learning How To Compose Tintinnabuli? If so, I am currently offering the first chapter of my new tintinnabuli composition course for free here.

Tintinnabuli in Spiegel im Spiegel

In Spiegel im Spiegel, there is one melody voice performed by the violin and doubled by the piano an octave higher. There are then a handful of T-voices in Spiegel im Spiegel, differentiated by the register. These exist in the three staffs of the piano: one in the bass, one in the high treble staff and then as the middle note of the arpeggiating figure in the middle staff.

In the bass and middle staff, the T-voice is below the M-voice. However, the T-voice occupies notes as close to M-voice as the F-major triad will allow. The T-voice in these staves is in a 1st-inferior relationship with the M-voice.

The higher staff uses two voice types, both of a superior quality. The dotted semibreve, which I do not include in the below example, uses a 1st-superior position. At least, that’s how it could be defined. Its occurrence is static, against the same note. Therefore, one could also say it is simply in a 3rd position!

The rest of this staff, which is typically dotted minims, is in a 2nd-superior position. Firstly, it is above the melody voice, making it superior. Secondly, there is a triad note available between it, the T-voice, and the M-voice. For example, in bar 22, if the upper staff was in 1st-superior, the pitch would be A5. Similarly, in 24, the note of a 1st-superior T-voice would be F5 as it is the closest pitch to the E, and a pitch of the F-major (tonic/root) triad. To which the T-voice is limited. However, these two notes are C6 and A5.

Counterpoint… “in a sense”

When I define the use of a tintinnabuli voice, this is really for lack of a better term. In a sense, the writing is contrapuntal as it deals with notes against notes and the artistic limitations that determine how the two notes work together. However, typically, in counterpoint teaching, contrary motion is king. Tintinnabuli, on the other hand, turns this on its head and will often boast oblique, similar and parallel motion between its parts. In this way, we could regard the qualities of tintinnabuli as a form or antithesis of counterpoint as we know it. I cannot really discuss this idea enough here, but I at least wanted to raise it for consideration.

Parallel 3rds

There is one voice unaccounted for in Spiegel im Spiegel, which we cannot easily define as a tintinnabuli or melody voice. This note is the first of each arpeggiated figure in the piano’s middle staff. This note takes on a diatonic pitch that is not confined to the root triad but runs in parallel 3rds with the M-voice. Therefore, its strictly parallel movement makes it difficult to define as an wholly independent M-voice, and its use of notes outside of the root triad are not concurrent with our understanding of the T-voice.

If we take the extract from bar 22 – 25 again, one can see how the first note of each arpeggiated figure begins a 3rd above the M-voice.

My assumption on Pärt’s use of parallel motion here is that it is a reference to the idea of mirrors that the title suggests. Are the parallel 3rds, like the other parallel and similar motions of the T-voices, a reflection of the M-voice?

Melodic Sequence

Melodically you might look at Spiegel im Spiegel and think the material is pretty bland. The melody typically comprises notes of a dotted semibreve value that move, often, by step. However, when one starts to look at its structure more closely, one can unpick several processes that constrain how the melody voice develops. For example, how the phrases of the M-voice grow and how pairs of phrases are bound together.

If we look at the melody with regards numbers of pitches per phrase first, we can see every pair grows by one pitch each time. For example, the first two phrases go G-A then Bb-A. The next two phrases grow by one note, going F-G-A and C-Bb-A. This process carries on throughout the piece culminating in a pair of phrases 9-notes in length.

This process of growing phrases is consistent with Pärt’s earlier composition Für Alina. In Für Alina, Pärt grows each phrase from 2 to 8-notes and then back to 2 again, adding one note each time. The simple additive and subtractive process of adding or taking away a note from a phrase seems to be a consistent limitation of Pärt’s tintinnabuli compositions, at least of this time.

Inversion/Symmetry

In Spiegel im Spiegel, everything orients around, or perhaps more aptly: emanates, from A4. A is the middle note of the T-voice’s tonic/root F-major chord; the melody always returns to a sustained A at the end of each phrase.

The consistent return to A4 reveals an additional process placed upon the melodies development. Not only does each pair of phrases grow, but each phrase within the pair is the diatonic inversion of the other. While one phrase might ascend in step to or from the pitch A4, the other will do the opposite. If we take the final pair of phrases, this relationship is easiest to observe.

At bar 102, we can see the melody voice making a long ascent from G3 to A4. If we were to define each interval distance numerically for each bar from 102 to 110, from A4, we would simply count down: 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2. The same is true for the second phrase. However, this time, the passage is ascending to A4. The two phrases are diatonic melodic inversions of one another.

Close: Reflection, contemplation and introspection

Pärt, when discussing his tintinnabuli music, raises the concept of duality. Tintinnabuli is grounded in his faith as an Orthodox Christian. The two voices represent body and soul, combining to exemplify the notion of sin. Spiegel im Spiegel, however, seems more pervasive: less sacred and more secular.

The idea of mirrors reflecting into one another is a striking image. However, for me, one cannot escape the idea of personally glancing into a mirror or, at least, looking upon those mirrors and thinking about what it represents. A kind of abstraction of oneself that paradoxically can only occur internally. With regards Spiegel im Spiegel, the concept of reflection could be the inextricable and generally inescapable toils we have in our conscience.

Spiegel im Spiegel has many reflective qualities as if parts of it are in front of a mirror. The pairs of phrases, for instance, perpetually growing––like the recursive reflection of mirrors facing one another––reflect each other. Each one is a symmetrical complement to the other.

Tintinnabuli itself, as we have touched upon, boasts reflective qualities. The T-voice is inextricably bound to the M-voice. It follows it everywhere, albeit constrained to the pure, grounding sonority of a triad. The M-voice is the body, and the T-voice is the soul. The M-voice is the objective; the T-voice is subjective.

There is subjectivity and objectivity to Spiegel im Spiegel, as there is subjectivity and objectivity to us and our experience of life. If you look in the mirror each day, you are still you, and the mirror is still the mirror. But do you see the same person? Are you the same person? Are you the reflection, or is the reflection you?

Interested In Learning How To Compose Tintinnabuli? If so, I am currently offering the first chapter of my new tintinnabuli composition course for free here.

Pingback: 5 Music Books I would Take into Exile - Any Old Music