The Lark Ascending has been a fascinating piece to study and analyse. I have really had to wrestle with not only the analysis but how to unpack the details of that analysis. In writing, I ventured down many rabbit holes trying to figure out how best to share my observations. Therefore, to make it easier for not only me to write, but for you to read, I have decided to create a series of “shorter” articles that unpack different aspects of Vaughan Williams’ composition.

The first of these articles… this one, will be on harmony. In subsequent articles I will be attempting to organise my thoughts and observations on the melody, melodic development/variation, arrangement and, possibly, the orchestration of RVW’s composition. These articles, particularly melody may also touch on the poetic inspiration on the piece, George Meredith’s The Lark Ascending. Today’s, on harmony, not so much (though I sneak a cheeky quote in).

In this article, as I said, I want to unpack the harmony of RVW’s composition, The Lark Ascending. While many parts overlap, and I would recommend reading with that in mind, I have broken this article down into pedal points, parallel chord voicings and modality (including modal modulation and interchange). Below is a contents list that boasts anchor links that will take you to specific sections and sub-sections of the article), should you be interested in anything specific.

If you’d like to be updated when we release new article and videos, sign up for the Any Old Music Mailing List.

Pedal points: centres, modes and harmonic layers

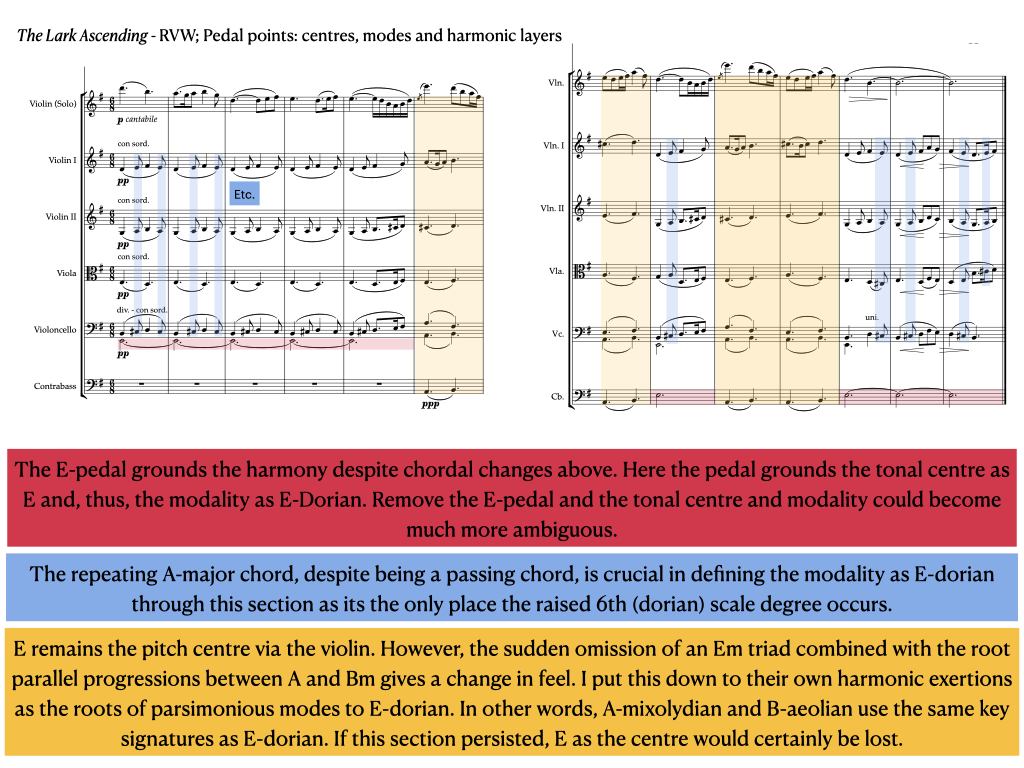

Starting with pedal points, RVW uses this harmonic technique at the beginning and end of the composition. We are going to focus on the beginning, after the opening solo violin cadenza where the piano/orchestra reenters (see extract below).

Pedal-points work in many ways in music. However, they typically operate by anchoring and confirming the tonal centre, or by imposing one on it. Vaughan Williams could be said to be using it in both ways in this extract of The Lark Ascending, though probably more the former: anchoring. In many respects he anchors the tonal centre, but due to the ambiguity in other parts of the texture, such as the chords and melody, it also feels quite imposing and, in a way, forced. (Which is not to say this comes across sonically or expressively in performance but, rather, when one approaches the music analytically, it can be interpreted that way.)

To define a mode, you need a tonal centre. For instance, to qualify something as Mixolydian or Phrygian, you need to know how the pitch material is relating to the root of the scale. For example, all the notes of D-major are present at this point of The Lark Ascending, but none of them—beyond the pedal—asserts itself as the gracious leader. Not even D or B, though we do have a B-minor triad in the accompaniment and a hint of A7, the dominant of D between the chords and melody. Therefore, due to these ambiguities, an underlying tonic note is helpful for clarifying not only the tonal centre itself, but the wider modality of the material. The pedal, while not sonically imposing or forceful in a practical sense, imposes and anchors E as the root and centre of this part of the piece.

Why is it E-dorian?

The pedal-point, in the extract we are looking at, is on the note E. This happens to clearly discern E as the root and centre of our mode, E-dorian. Why E-dorian, you ask? Well, just as the E-pedal tells us our tonal centre is E, there are a cheeky combination of notes that relate to this root in particular ways, which tells us the wider modality is Dorian, rather than simply minor or aeolian.

If you recall, while talking about the pedal point and wider ambiguities, I said the pitch material of this section could be arranged into a D-major scale. This is helpful, as it tells us two things: (1) that there are the notes of a D-major scale and (2) E is the second scale-degree of D.

These two things are helpful in combination because if we arrange the notes as though they are ascending from E, rather than D, we get an E natural minor/aeolian scale but the 6th scale degree is raised a semitone from C to C#. These minor details are actually a major detail (pun intended), because it tells us that the mode is minor. Dorian is a minor mode. The raised 6th is important because that is what we consider, in a minor mode, to be the “dorian 6th”.

Side note (further explanation of Dorian)

Another way to think about this is if we transpose everything into C. As you may be aware, if we have the notes of C-major but start the scale on different pitches of that scale, we get different modes. Starting on D, which is the second-scale degree of C-major (or C-ionian) gives us D-dorian. E gives us Phrygian; F equals Lydian; G, Mixolydian; A, Aeolian and B, Locrian. The same applies, in transposition, to every major scale. In D-major, the second degree leads to a dorian configuration of notes.

Why is this section so ambiguous without a pedal?

If we imagine this section without the pedal, it’s pretty tough to nail down a definitive tonal centre. And, even with the pedal, this still remains true as many of the parts of the texture are able to do what they want. (It’s quite remarkable, actually!) Persichetti identifies a phenomena in modal writing, which occurs when the tonic is not sounded enough to be intuited as the centre: “much melodic reference must be made to the tonic if one wishes to stay within the mode; otherwise the tonality will switch to major under the ionic power of the tritone.” (Twentieth Century Harmony, pg. 36) Without the pedal, the same could be true for this section.

Perhaps, without the pedal, this section could fall into the ionian trap that Persichetti puts forward. As I said previously, although there is no D-major chord in the harmony, there is the pitch content of D-major, an arguable emphasis on the note D in the violin solo and a chord sequence that is not wholly at odds with D-major despite the lack of tonic. For example, the parallel chord progression in the strings progresses in a series of 1st-inversion chords G – A – Bm – A. (The first chord becomes Em7 with the pedal. Moreover, in the orchestral version it could be read as an Em7 2nd-inversion chord as E occurs in the Violas.) In D-major this would be IV – V – iii – V. Moreover, in bar 2, the auxiliary note, G, in the violin, albeit occurring before the A-major chord, is the dominant 7th. Which is the powerful “tritone” structure that Persichetti is alluding to when he talks about modes shifting to major.

When we consider this concept further, it is worth noting that C# is omitted from the solo violin part. RVW opts for a hexatonic and, arguably, pentatonic pitch collection in the Violin. Perhaps, RVW felt the leading tone, a strong tendency note in tonal music (partly because of that tritone), in such a prominent position could pull us towards D-major more definitively. Or, at the very least, the solo would start to be pulled towards D-major. Therefore, leaving it out ensures the dorian modality is the prevailing sound, and not ionian.

The result, as I said, is a solo Violin part that can move quite indiscriminately, drawing out the optimistic, soulful quality of dorian that underpins it. Rising, rounding, dropping “the silver chain of sound…to lift us with him when he goes.”

Parallel Harmony

In discussing the pedal points in The Lark Ascending, we saw how ambiguous the various parts of the texture are harmonically. Diatonically and with the pedal, everything in the opening sections is clear. However, the middle layer, thinking horizontally and texturally, which carried a clear triadic progression, is somewhat ambiguous. A part of this is a result of the particular parallel chord voicing that RVW uses in this section and, similarly, in others.

RVW’s open 5th Voicing

In many of the sections of The Lark Ascending, RVW uses parallel chord progressions. Although the voicing varies between root and 1st inversions, the voicings are typically open, emphasising a parallel 5th between voices of the chord. In the 1st inversion chords this is between what could be described as the tenor and alto voice, if we imagine the voices ascending: Bass, Tenor and Alto from bottom note upwards. In the root voiced chords, the parallel 5th occurs between Bass and Tenor, often as the bottom outer voices.

Types of Parallel Harmonic Progression

Referring again to Persichetti’s harmony, he identifies two types of parallel harmony: “Real Parallel Harmony” and “Tonal Parallel Harmony”.

Real Parallel Harmony is where each note of the parallel chords moves by the same interval. For example, the chord progression: C – D – E, where all chords are major, would be a real parallel progression as each note moves up by a major 2nd.

Tonal Parallel Harmony is where the notes stay within the key of the music. C – Dm – Em, for example, would be the Tonal Parallel Harmony equivalent of the previous progression, assuming we are in C-major. The difference is that some voices/notes in this second progression will move by a minor-2nd, where others move by a major-2nd.

RVW predominantly uses the latter, Tonal Parallel Harmony, which results in a kind of undulating, combined mass. Persichetti describes tonal parallel harmony as being “an expanded textural equivalent of a melodic line;” (pg. 198). Which is sort of what I am driving at with the phrases mass and undulating. Rather than one voice moving up and down, there are three. This results, as I said, in clear triadic harmony, but does little to give prevalence to specific tendencies within the scale. Everything is moving in service of the other parts, rather than of its own independent melodic will.

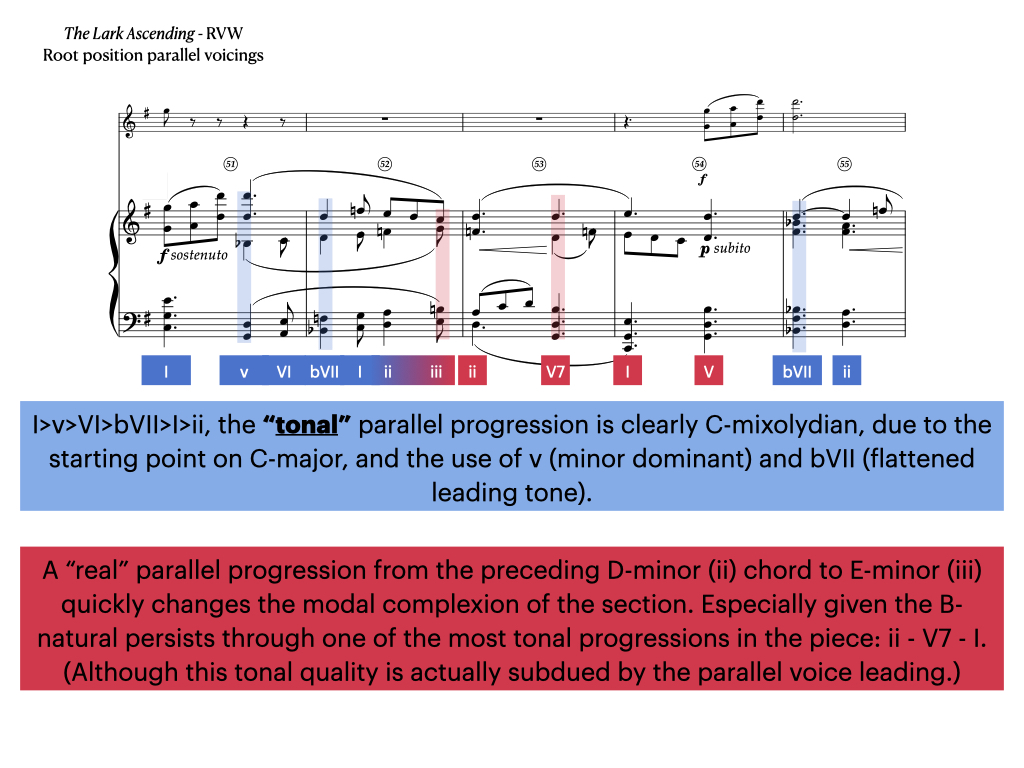

Root position parallel voicings

We have seen the 1st inversion parallel voicing in action. Let’s now take a look at the root position chords. These occur in the previous extract that we looked at, in bar 6. However, to bring another part under the microscope, let’s take a look at the use of root parallel voicing somewhere else, notably bar 51 to 55.

In this passage, the music suddenly shifts to C-mixolydian, from E-aeolian, and then to C major or ionian via a rare ii-V7-I progression. The passage is a remarkable demonstration of how to use parallel progressions. For example, parallel progressions can get bland quickly. One way in which RVW avoids this in other parts of the work is by switching between parallel and non-parallel voiced sections. However, another strategy he uses, which is on demonstration here, is to have another part of the texture in contrary motion. As the triads rise the melody moves downwards, and the texture contracts, before moving outwards again. Contrary motion is a boss.

The other thing that is on demonstration here, to an extent—at least momentarily—is “Real Parallel Harmony”. If you notice in my extremely amazing annotation below, you will see I have placed the ii and iii of the progression in a cool gradient coloured box. To avoid the diminished triad, which iii would be in mixolydian, RVW raises the Bb to B. The result is a real progression that RVW uses to shift modes from mixolydian to ionian.

Persichetti describes real parallel harmony as having “a tendency to sever connections with any one key.” In contrast to this “Tonal parallel harmony…tends to preserve a modality.” (p.198). This is what happens here. The tonal parallel harmony is used to assert mixolydian, but RVW takes the opportunity to raise the 7th scale degree, pivoting into a brief moment in C-ionian.

Weak Motion

Despite the ii-V7-I progression, in the progression that closes this phrase, the cadence is somewhat nonchalant. The parallel voicing, as said previously, is something of a melodic mass, despite being clearly triadic. Therefore, lines do not reach their own ends, they do what the bass wants to in this instance. The result is a cadence that is less declamatory than one might expect of such cleanly triadic harmony.

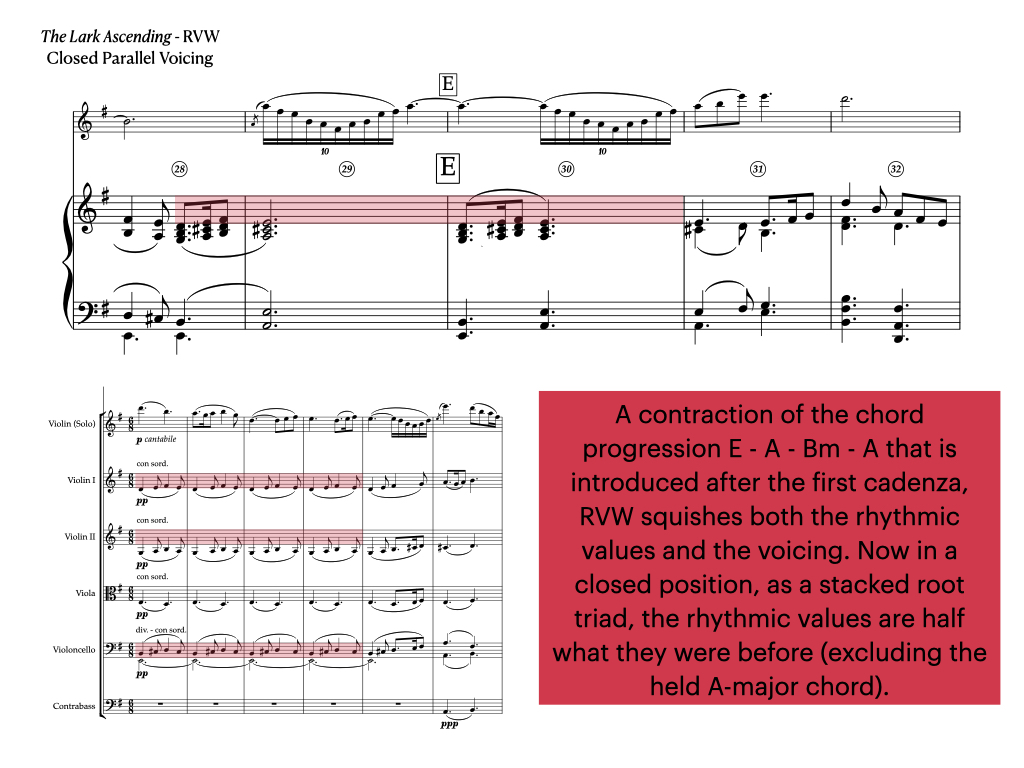

Closed Parallel / Harmonic Planing

Another voicing used by RVW in The Lark Ascending, though less frequently, is the closed parallel voicing. Or, harmonic planing, as it’s known by many. This type of voicing is used early on in the composition, shortly after the pedal extract we analysed earlier. In fact, the ascended dotted rhythm idea, is introduced in the strings during the pedal section. Initially in an open 1st inversion position at this point, RVW eventually puts it into a root and closed position for oboe and horns.

The idea is essentially a contraction of the rolling chord idea: E (or G, as we labelled it without the pedal) – A – B – A. The values, excluding the final A chord are diminished to half their value. RVW not only contracts the voicing, therefore, but the rhythm too. The textural span is shorter, so are the rhythms.

The effect is both similar and the same as the earlier parallel moving chords. The undulating mass is denser, but, perhaps, more focussed.

Modal Interchange

In the previous example, we saw how a tonal parallel progression, with a moment of real parallelism thrown in was used to move from C-ionian to C-mixolydian. This process, as the C remains the root of the mode, is called Modal Interchange. Modal modulation is where the tonal centre moves but the mode remains the same. For instance, a move from C-mixolydian to D-mixolydian would be a modal modulation.

Witholding Harmonic Information: Interchange and Modulation

RVW uses modal interchange, as in the previous example, and modal modulation, sometimes together. He will often use these at climactic moments or as a means of discerning sections. For example, a modulatory tactic that RVW uses in The Lark Ascending is withholding notes, by using a pentatonic or hexatonic set. The result is a tonally and modally more pliable mass, where the withheld notes can return as modally important pitches. Or, the freer harmonic material can be used to pivot into a modally and tonally new section. He does this prior to the C-mixolydian section, withholding G and C.

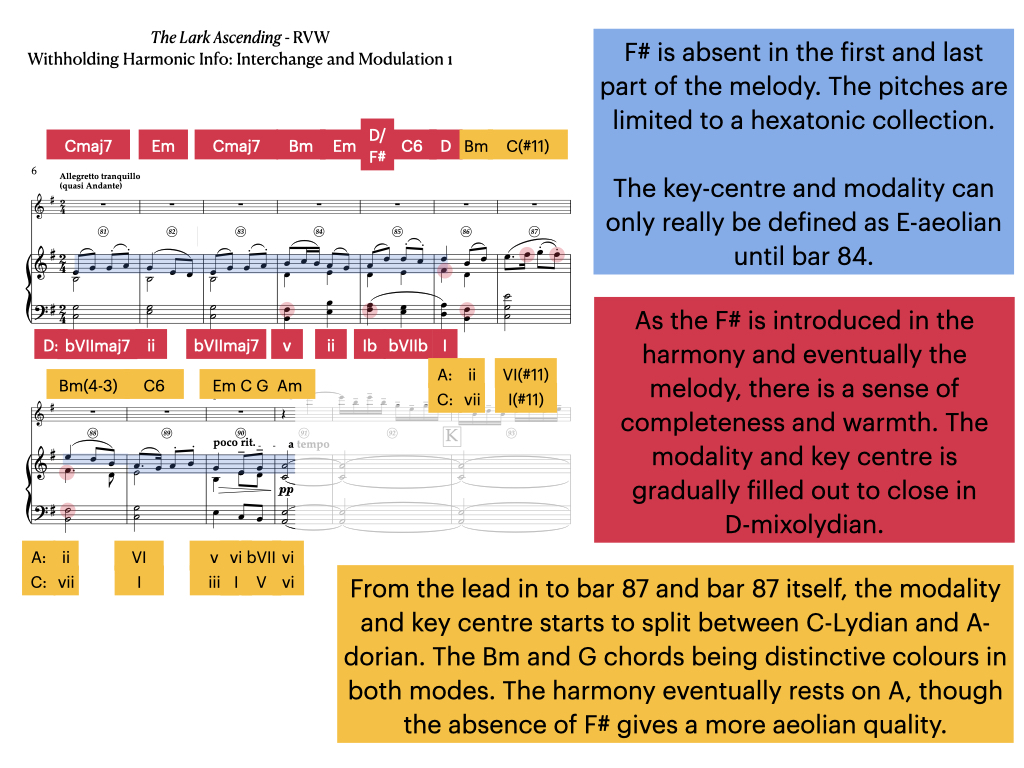

Another section where this is apparent is at the beginning of the middle section marked Allegretto tranquillo (quasi Andante), bar 81. Outlining the two important key centres of section A, RVW gives us a progression that starts with root parallel C-major and E-minor chords. Closing the phrase with sudden contrary moving parts, the section ends with a cadence in D-mixolydian.

Similarly, the next phrases that follow the D-mixolydian cadence oscillate between C-major and B-minor. Using parallel motion again, the voice leading starts to move more independently at the close of the section. The phrase ends on A-minor the important minor dominant of D-mixolydian. However, I think by this point A becomes the modal centre, leading to a second modal modulation and interchange to A-aeolian as the crucial F# (scale degree 6/dorian note) disappears.

The Lark Ascending’s climax: Modulation and Interchange

One of my favourite passages in this piece, and the one we will finish on, is at the return of the A-section, marked Tempo del principio (bar before rehearsal mark U). Marked forte sostenuto we have a reprisal of the theme from the first extract we looked at in this article. However, rather than presenting the same material, RVW resets it in a gyroscopically turning process of modal interchange and harmony.

A rising stepwise bass line, against a largely descending melody line, the section starts in B-aeolian. Changing as the bass line rises, not too dissimilarly to the C-mixolydian section we analysed, the bass line interchanges Aeolian for Dorian, presenting an Em/G chord straight after the melodic G# over an F#-minor chord. Culminating on a B, the bass line starts to fall back down and the section ends on an A-major to E-minor progression that starts our large scale move back to E-dorian, where the whole piece started. The return to E is accentuated by a two bar pedal on B, the dominant of E.

It’s a magical moment. I refer to it as gyroscopic as it feels like multiple parts are turning. The pitches are all trying to rally around a tonal centre, these pitches—though not drastically—change. As the tonal centres move, so too do all the pitches around it, there is so much motion and so much harmonic colour, despite there being only subtle chromatic changes.

Close

Modality is such a simple but complex concept. It is both in stasis and motion all at once. The Lark Ascending has proven a wonderful opportunity to “get our hands dirty”, seeing modality in action. Concise in its key centres (predominantly E and C, though we pass through some others such as D and B) and the modes it uses (predominantly Dorian, but also moments of Aeolian and Mixolydian), RVW demonstrates an harmonic range and fluidity that modality can unlock. Often switching parsimoniously between modes of the same pitch material, the tonal centre might be adjusted (modal modulation), or he might keep the tonal centre and subtly alter a pitch to change its mode (modal interchange). Or, for climactic moments, he might move mode (modal interchange) and tonal centre (modal modulation), elevating the harmonic tension and motion as one feels the landscape shift beneath you.