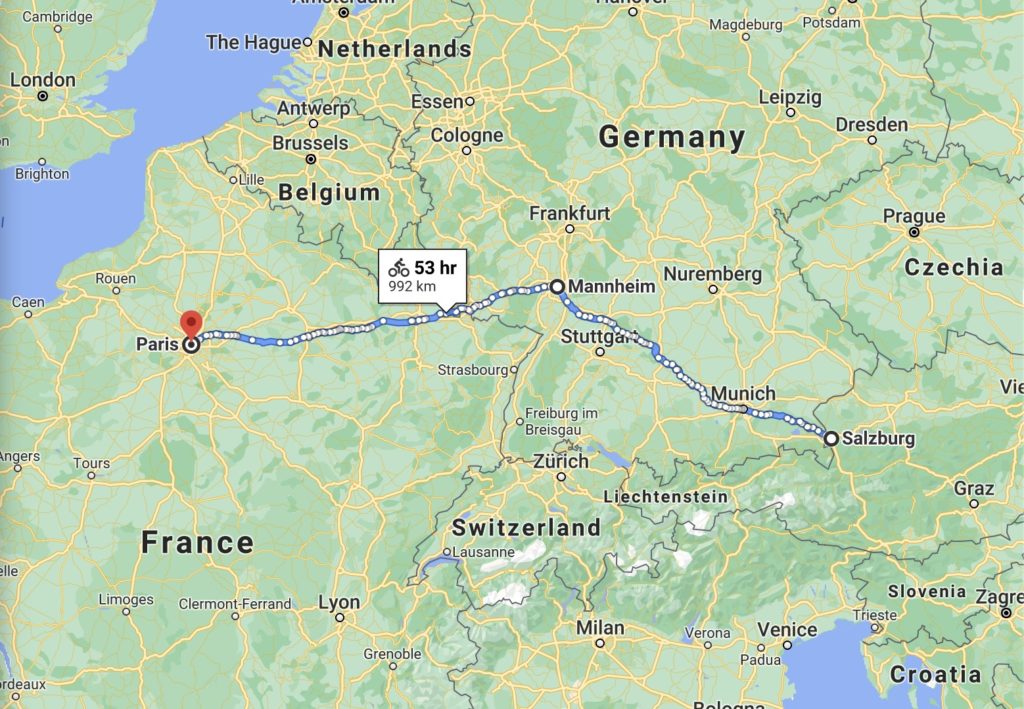

In early 1778, Mozart was touring from his home in Salzburg to Paris. Stopping in Munich and Mannheim first, Mozart composed many sonatas on this journey. A collection of these includes seven Violin Sonatas (No. 17 – 23). The E-Minor Violin Sonata, No. 21/K. 304, is the only minor key sonata in this collection. I decided to take a look at this sonata, in part for that reason, but also because I found the clarity of its composition compelling. Using texture to clearly state themes and then present interesting variants, I think it’s a good demonstration in what I think can be easily forgotten as a composer or arranger: less can be more. Below I explore the work’s contextual origins, before analysing the first movement in more detail, focussing on its composition.

Continued below…

If you’d like to be updated when we release new articles and videos, sign up for the Any Old Music Mailing List.

Context

A turbulent period for Mozart. The E-minor Violin Sonata (K. 304) was composed while he was on a tour that would take him to Paris. He would also stop off at Munich and Mannheim. Intended as a trip to grow and spread Wolfgang’s reputation as a composer and performer, Mozart, along with his family, was hoping he might also escape Salzburg and Archbishop Colloredo, gaining new employment in a more favourable court, where he would be allowed to flourish.

Analysis Video

Context Continued: Mannheim

Mannheim, a court held in high regard for its musicians during this time, is where the E-minor Violin Sonata originates, before being completed in Paris. There is speculation that the Violin Sonata was written as a response to Mozart’s mother’s death. However, according to the description of the linked performance below, Anna Maria’s death, in Paris, succeeds the first movement and, possibly, the second movement’s completion, undermining this hypothesis. (I made an attempt to find the sources that discuss the paper dating in the above source. However, I was unable to locate them. If anyone knows where it is, I’d love to know!)

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

The Lark Ascending (Music Composition Analysis) – Ralph Vaughan Williams (Article 1 – Lessons in Harmony)

How to repeat melodies without them getting boring… [Video]

5 ways of Understanding woodwinds

Arabesque No. 1 – Claude Debussy (Music Composition Analysis)

Spiegel im Spiegel – Arvo Pärt

Salut D’amour – Edward Elgar (Music Composition Technique Analysis)

Possible personal, life events behind the composition

Surrounding grief-stricken laments, there is a more compelling argument around the later A-Minor Piano Sonata No. 10, k.310, which does succeed Anna Maria Mozart’s abrupt death and is the first minor-key composition to do so. Julia Nagel puts forward a psychoanalytical case that outlines features in the Piano Sonata that set it apart from others composed by Mozart, and why the composition, therefore, could be a response to his mother’s death.

Toying with this line of enquiry, one can speculate on a different emotional basis for the composition of this E-Minor Violin Sonata. While in Mannheim, Mozart became particularly fond of Aloysia Weber, a soprano who was the older sister of Wolfgang’s later wife, Constanze. (The portrait of Mozart I use in the image for this post is actually by Aloysia’s later Husband, Joseph Lange, Mozart’s eventual brother-in-law.) Delaying his departure, it was only under duress that Mozart finally succumbed to his Father’s pleas to move on to Paris in March of 1778. Its possible, although speculative, to suggest the E-minor Violin sonata is a response to this duress, at having to leave Aloysia, in Mannheim, and move on to Paris.

The Mannheim style combined with raw emotions?

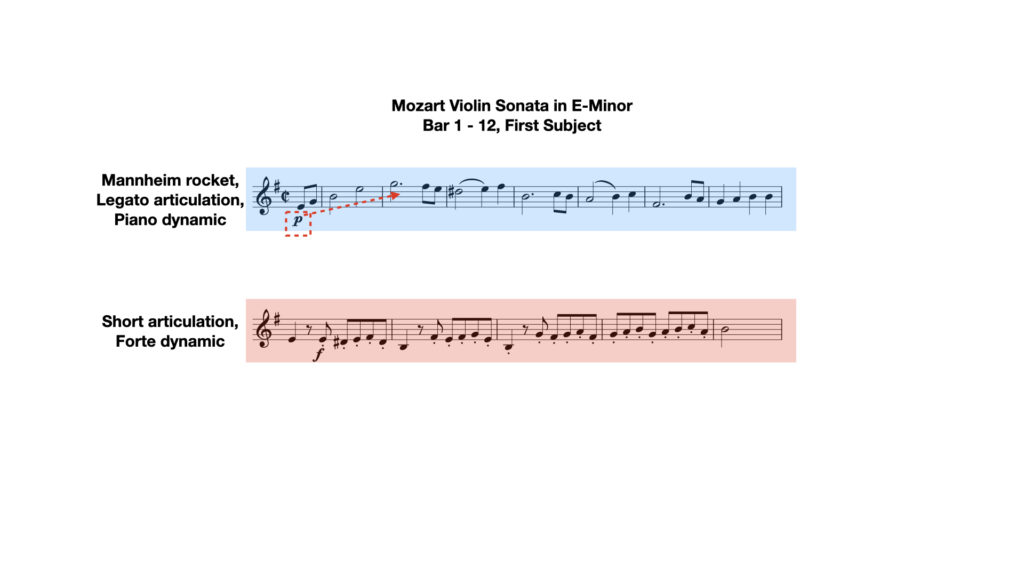

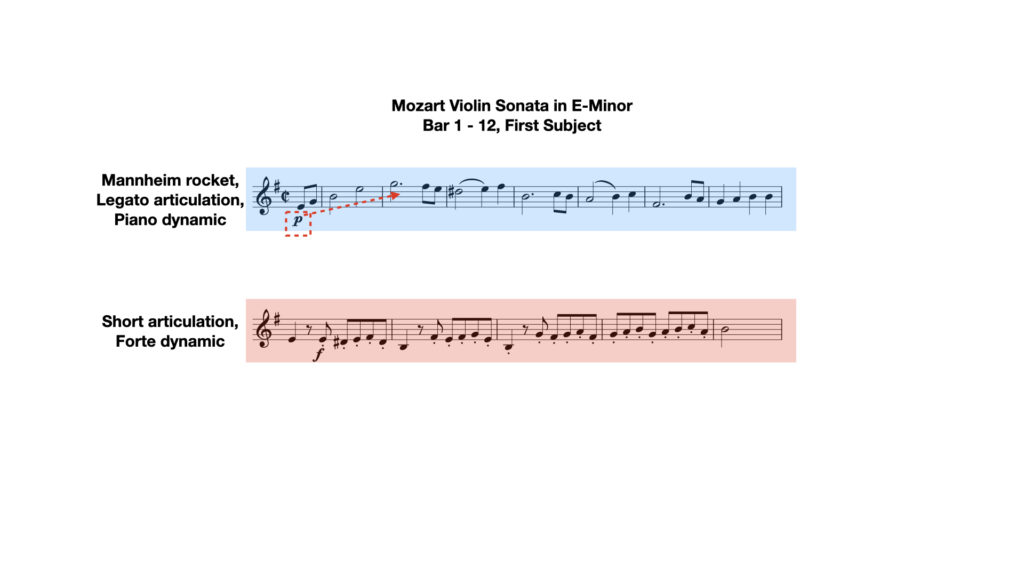

There are several novel qualities in the Violin Sonata that facilitate speculation on its geographical and emotional origins. For instance, the 1st subject of the Violin Sonata’s 1st movement has a combination of interesting characteristics. These are its upward skipping contour, reminiscent of a Mannheim rocket, combined with the bel canto style lyricism typical of Mozart’s writing. Emphasised further by the minor tonality, these qualities generate a potent feeling of melancholy, reflective of his reluctance and despair at leaving love behind in Mannheim.

The second quality of this first movement is its juxtapositions of dynamics and articulation, creating abrupt shifts between brooding melancholy and irritable frustration. There are regular switches between forte and piano, frequently accompanied by alternations from legato to staccato playing. Considering the second movement as well, which uses dolce and sotto voce markings, along with crescendos and diminuendos, to add further dynamic range, these are significant details. Across Europe, the Mannheim court of musicians had a reputation for being particularly capable of realising such dynamic nuances and sudden changes in their performances.

A sensitive-styled second movement?

The minuet and trio, second movement, boasts additional emotional qualities of lovesickness. In listening to and analysing the piece, the outer minuet sections remind me of emfindsamer stil or the sensitive style of music composition. Notably explored by JS Bach’s sons CPE and WF Bach. Using suspensions, appoggiaturas and melodic and accompaniment textures, there is an undeniable sensitivity to this movement that could be attributed to Mozart’s sadness at having to leave Aloysia Weber behind in Mannheim. Or, if the composition of this movement does succeed the death of Anna Maria Mozart, then it could also be a response to that. Referring tentatively to the source I’ve not been able to… source, in original form at least, the second movement was written later.

Context Round-up

Speculative, I find these musical and contextual relationships compelling to explore. One can find a clear influence of distinct Mannheim features and sensitivity in Mozart’s Violin Sonata. Often described as a sponge, the deliberate referencing and use of such musical language, by Mozart, are very plausible. The rare use of a minor mode also facilitates speculation on its emotional origins. However, albeit less exciting and mystical, the reasoning could be much more straightforward. Mozart had composed five Violin sonatas on the trip already. Each of these was in a major tonality. Perhaps, in a bid to demonstrate versatility in his craft–to potential employers–Mozart composed a minor tonality composition that showed off his ability to express sensitive emotions? Come to think of it. I think I prefer that last one. I wish I’d thought of it sooner!

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Mozart – Violin Sonata No. 21, E Minor (K. 304), 1778. [Score Video]

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Composition Analysis

Mozart’s Violin Sonata in E-Minor, K. 304 has two movements: a sonata-allegro and a minuet and trio. Two movement sonatas were not unusual at this time as, while sonata form was perpetually developing, these were its formative years. Just as the symphony was transitioning from three to four movements, the sonata was going from two to three. This sonata is one of the last that Mozart composed in two movements. He experiments with the 3-movement schema when composing his piano sonatas during this period. (K. 309, Piano Sonata No. 7, for instance, has three movements. Its composition is believed to be a little before the E-Minor Violin Sonata.)

In this analysis, I want to focus on the first movement. I believe there are valuable concepts that can still be learned from this movement that will enhance our thinking as composers and arrangers: particularly the presentation and control of musical ideas. Therefore, for this analysis I want to pay particular attention to the overall structure of the first movement: how Mozart orders his ideas within the larger sonata schema; and how he develops his themes, looking particularly at his use of fragmentation in polyphonic textures.

Structural Overview

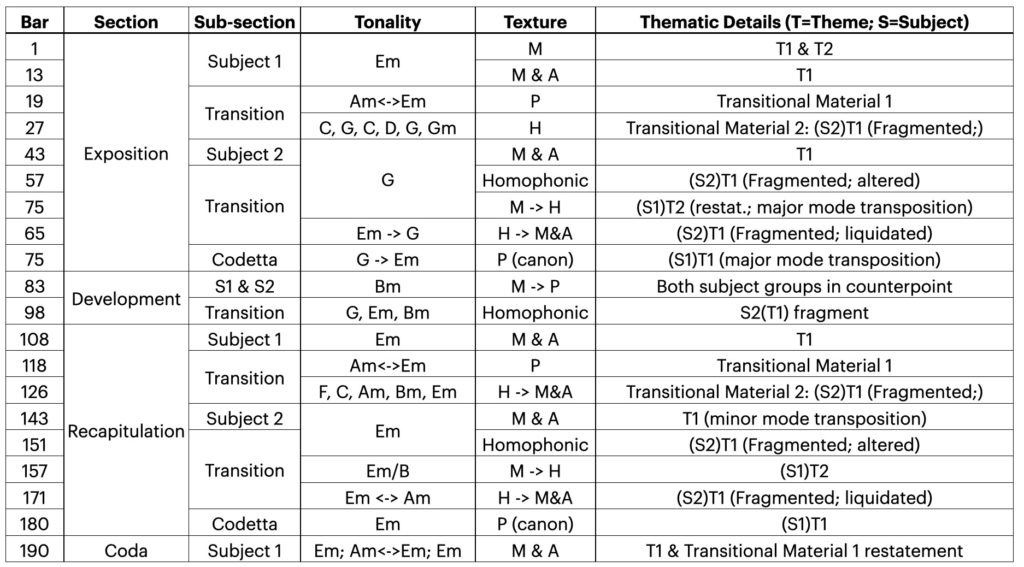

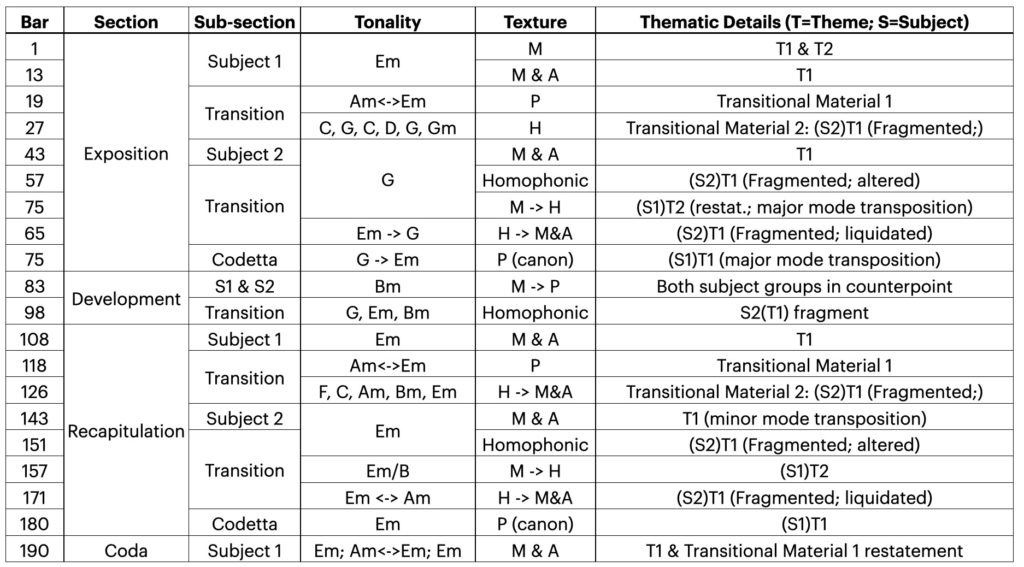

The structure of K304 is a broader sonata procedure. A form, as I have said, in developmental flux, it is possible to distinguish functional periods within the Violin Sonata that can be defined and labelled as sonata form sections. For instance, the work has a clear exposition, where Mozart communicates the thematic material to his audience. The development section is where the bulk of thematic variation is. Although in reality, the development of ideas is not confined only to this section and Mozart does compelling things with his melodies while in transition, between statements and restatements of the main melodies. The development section is, typically, in a different key to the home key of the sonata, while the recapitulation restates themes in the home key. Mozart follows this strategy by modulating to B-minor for the beginning of the development section, returning to E-minor in the recapitulation.

Tonality

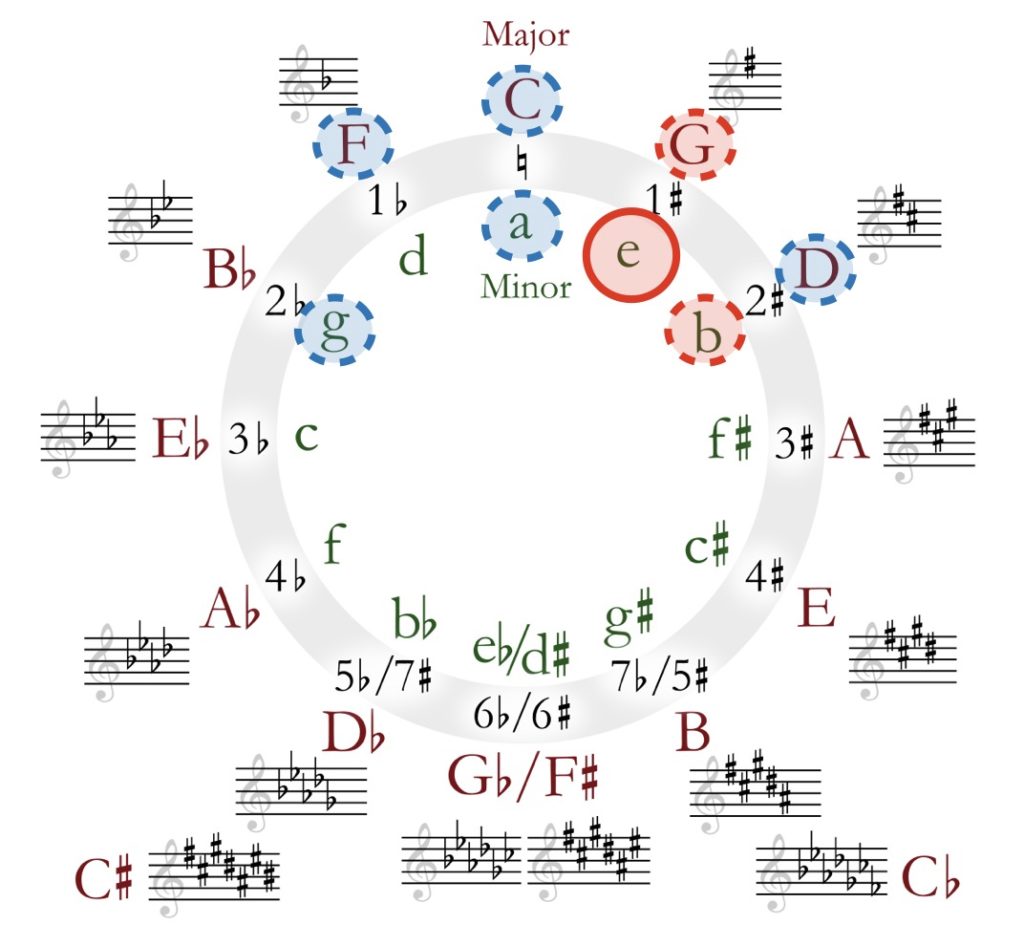

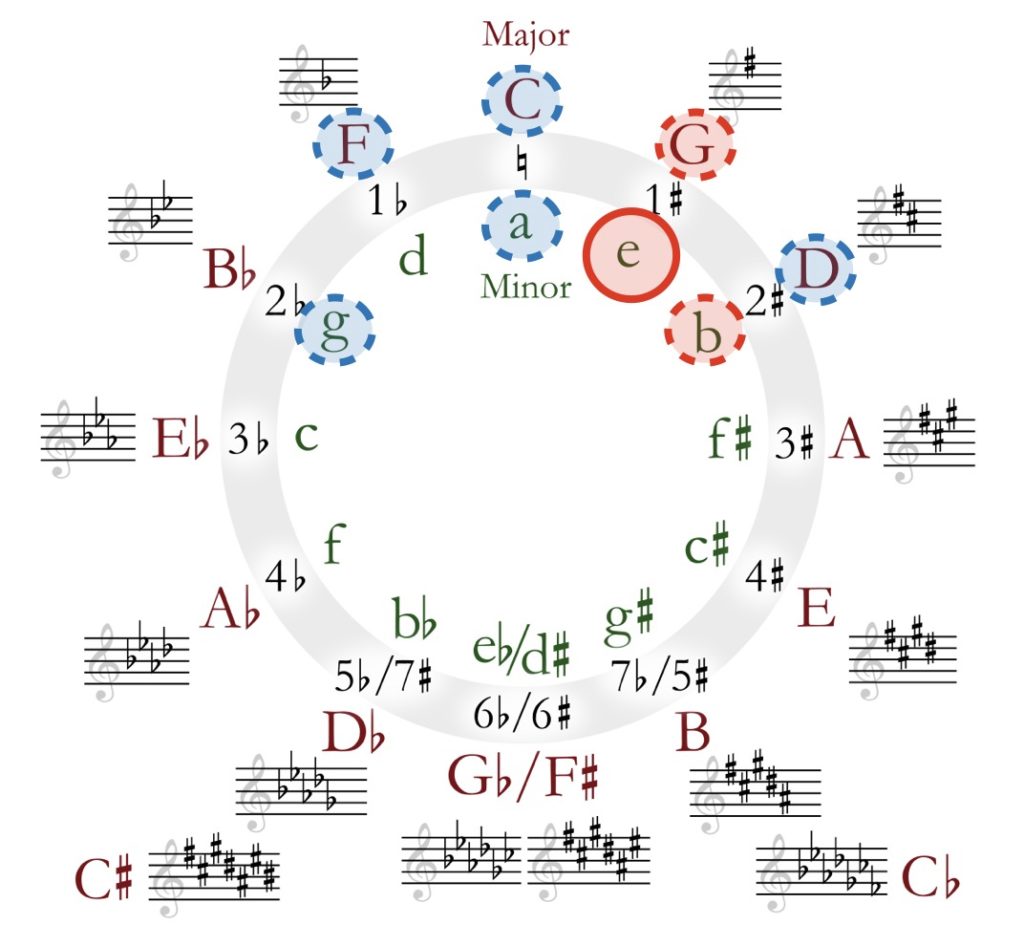

Large Scale Tonal Schema

Aesthetic for this period, Mozart uses closely related keys. And, on a larger scale, Mozart follows a typical modulatory schema. The work starts, in the exposition, and ends, in the recapitulation, in the home key of E-minor. For the second subject and development section, Mozart modulates to two different keys. In the second subject, the composition moves to the relative Major, G, and in the development to the minor dominant, B. A typical strategy of this time, many works, including sonata form movements, start in the home key, modulating elsewhere through middle sections of the composition. Usually to a relative or dominant key, which is what Mozart does here.

Tonal Landscape: Small & Large Scale

Including smaller scale modulations, if we look at the circle of 5ths, we can more easily see the closeness of all the keys Mozart uses in his work. To distinguish the larger scale modulations, I use red circles. For the smaller, passing modulations I use blue circles. In combination with the above table, the 2nd subject and development section are where the work stays within these different keys for the longest time. It is in the transition section where we have passages that pass through many keys quickly, but in so doing, we travel the furthest from the home key of E-minor.

The most distant modulation here is the parallel major-minor switch in the expositions transitionary section, where Mozart modulates directly from G-Major into G-Minor and then back again. However, despite being visually more distant, the fact the two are parallel tonalities means they share the same root and core harmonic tones. For example, Mozart uses a D-pedal through this passage to both underpin the G-minor but also build excitement, in the form of a dominant preparation, for the second subject, which is in G-Major. D is the shared dominant of both G minor and major, being the 5th degree, or V, of G (major and minor).

Texture

Along with modulations, Mozart also uses texture to create interest and clarity in his thematic material. (Similar to Guiraud’s use of texture for Bizet’s Farandole.) Melody and accompaniment is the prominent texture of the composition. However, Mozart also makes use of Polyphony. Homophony is used sparingly, used most frequently within inner voices as part of a larger melody and accompaniment texture.

Clear Exposition Textures: Monophony and Melody & Accompaniment

To me, the opening monophonic texture of Violin and Piano in octave unisons is a startling opening. Especially when mixed with the piano dynamic level and brooding minor tonality. This response could, in large part, be due to Mozart’s often upbeat, major tonality compositions. It is a stark contrast within the larger context of his catalogue of works.

Mozart uses monophony, or more frequently, melody and accompaniment in sections where initial thematic statements or restatements happen. In these passages, the accompaniment part switches between two forms. Firstly, broken chord, Alberti bass figurations and, secondly, chordal structures, reminiscent of homophony. (While homophonic between the chordal voices, often in a particular hand of the piano, in the larger textural context they play the role of accompaniment.)

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Exciting Textural Contrasts: Polyphony & Counterpoint

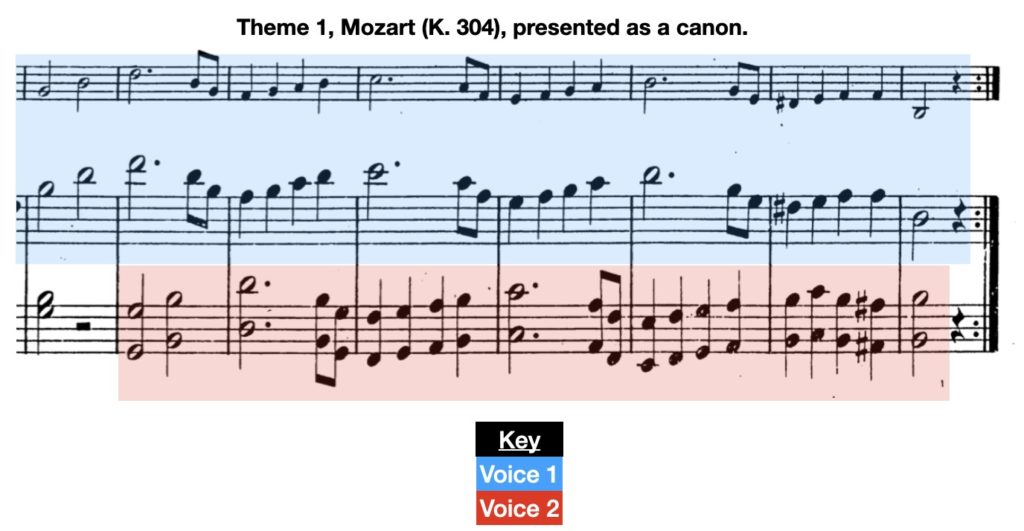

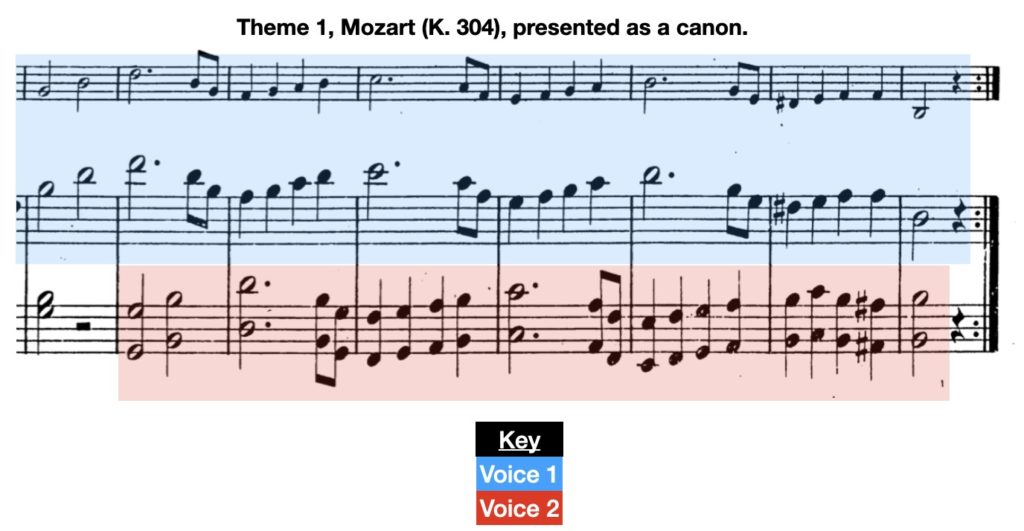

Mozart also uses two forms of polyphony in this composition: canon and imitative counterpoint. In the passages that I label as codettas, Mozart presents the first theme, of the first subject, in a 2-part canon. This textural distinction, along with their positioning: just before the repeat markings, is what led me to distinguish them as codettas. In the transition sections and development section Mozart uses imitative counterpoint. Clearest in the development section, this is where Mozart counterpoints themes of different subject groups. He uses polyphony as one of the large-scale ways in which to develop his material.

I do not think it is an accident that there is a correlation between exposition, restatement and melody and accompaniment textures, while polyphony is reserved for transitional and development sections. Melody and accompaniment textures inherently elevate the prominence of melody. In stating his themes, Mozart wants us to identify them with ease. The satisfaction of a sonata form, from a listener’s perspective, is being able to hear these themes and then spot them in more complex variations and settings. In other words, as the composer, Mozart wants us to identify his themes, so he can show us how clever he is in developing them.

Melody

Thematically I have already alluded to two ways in which Mozart develops his material. One of these is through modulation, taking his themes through different keys. Another is through setting them in different textures. These changes are broader, with Mozart imposing the challenge of fitting each idea into a new tonal or textural context. However, Mozart also uses a smaller-scale developmental technique known as fragmentation. I want to highlight his use of this technique, by extracting the original melodies and some of these developments, as they are still useful techniques that we can use today in our music-making.

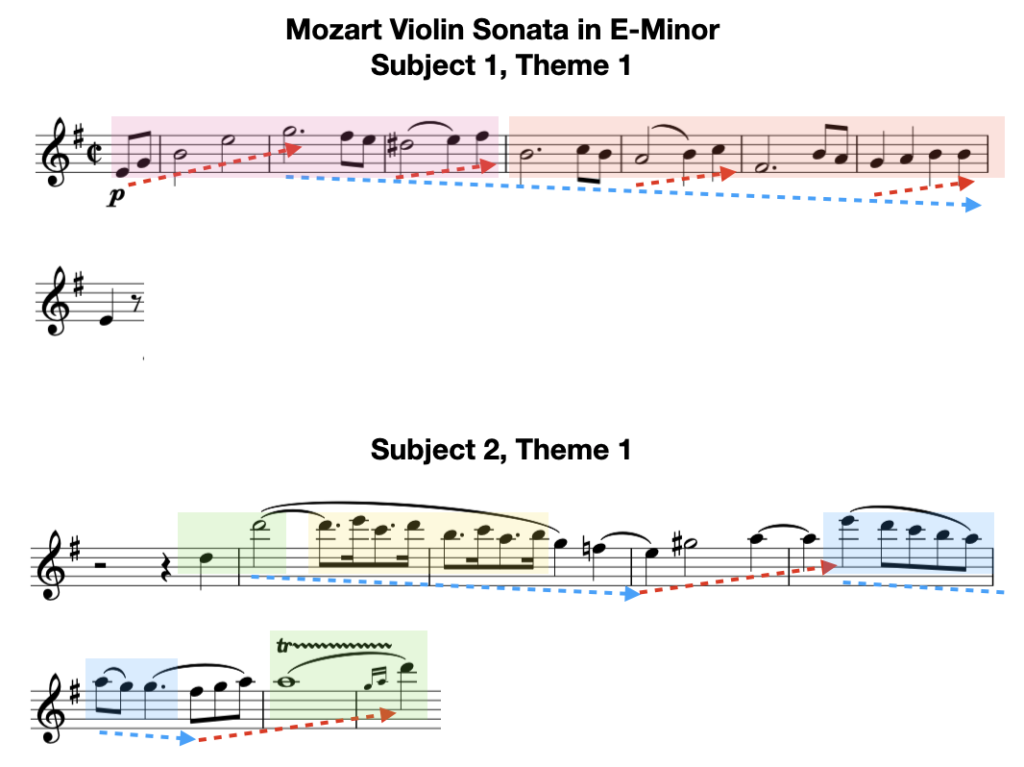

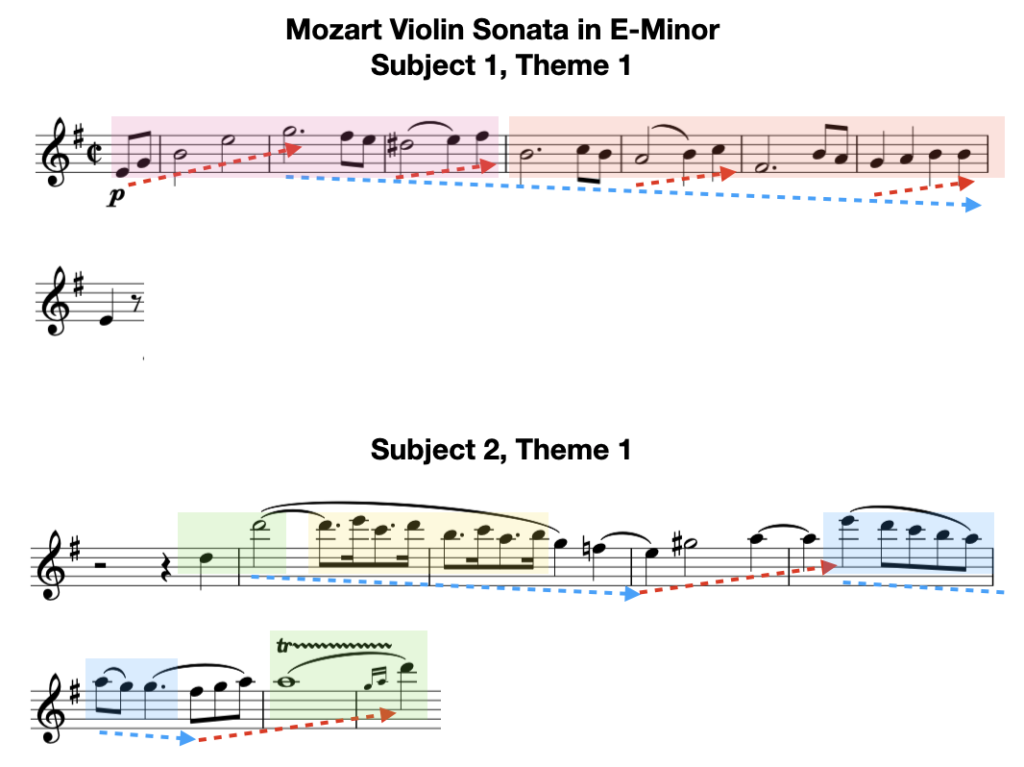

Subject 1, Theme 1

The first theme that Mozart presents is a lyrical, bel canto style melody. With the anacrusis it spans 8-bars. The second 4-bar phrase is important in the development section, as we will see, while its opening arpeggio figure that I liken to a Mannheim rocket is distinctive. Its inner contours are largely upward, but on a larger scale it is always falling back to where it started.

Subject 2, Theme 1

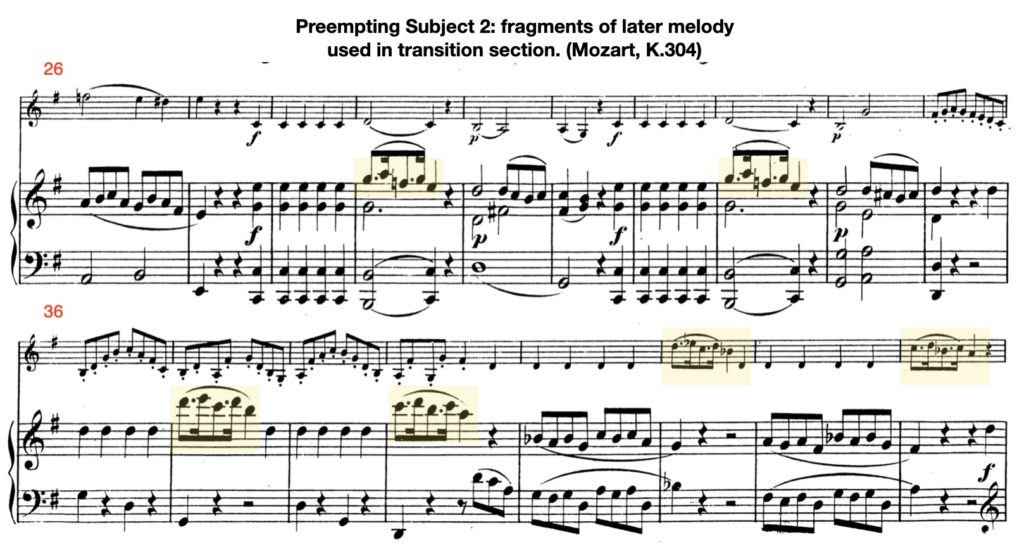

The first theme of the second subject has two distinguishing characteristics. The first is its emphasis on dotted rhythmic patterns, followed secondly by its V-shaped contour. The dotted rhythms are particularly important to developments of this theme within the transitional sections of the work (yellow annotation, in below image). While the descending, straight quaver passage (blue) and octave leap (yellow) become important in the development section of the composition.

Distinct from one another, below, I have extracted each of these themes, annotating their characteristics.

The second subject theme has the most smaller-scale developments. In the transitional sections of the exposition and recapitulation, we can extract several iterations of the dotted rhythm, fragmented from the theme. While it is possible Mozart composed the work linearly, there is further reinforcement of the lessons learned from arranging London Bridge, and the non-linearity of ideas in the composing process. For instance, it is also just as possible that Mozart had composed his two subjects and then figured out the transition afterwards.

Melodic Development

In the development section, Mozart uses larger fragments of the themes, placing them in counterpoint. The use of the first theme is clear, appearing first in full form. The only apparent change, initially, is its transposition into the key of B-minor. Mozart then fragments this theme, focussing on the second 4-bar phrase, counterpointing it with both itself and a fragment of the second subject.

The second subject’s use is less obvious. Mozart fragments the second portion of this theme where the melody descends in straight, rather than dotted quavers. He then alters the rhythm, while maintaining key intervallic and contour features. Placing the extracts together, with annotations demonstrates the second subjects use in this section of the composition.

Placing the themes in a different texture is a larger-scale way of developing the material. Mozart can extract larger fragments, juxtaposing them to create a compelling moment of polyphony. All the while he is not reinventing the wheel, using material he has already exposed.

Conclusion: the takeaways

I always think of sonata, or any established form for that matter, as being like a species of animal. Similar forms have underlying skeletons that might be indiscernible beyond species alone. However, when you give them their form, adding the flesh, skin and hair (if its fortunate enough to have any…) the variety becomes much more vast. We can identify individual people or animals through their appearance, just as we can identify different pieces. However, if you look under the surface the structures can be very similar.

Thinking about this similarity of the underlying structure but the difference of outer form. The first, broader, takeaway is one of exploration. Why not explore established forms in your writing? Mozart, in my opinion, was an exceptional exploiter of form, creating novelty within its confines. I think this is also why his music has entered and remains firmly within the western musical classical canon. In using forms we understand his music immediately becomes more accessible as we know how to listen to it and, as a result, appreciate it. Now, appreciation might not be an aesthetic goal and I’m not saying it should be, but its a concept that is helpful to be aware of.

On a smaller level, Mozart’s E-Minor Sonata, No. 21 (K.304), demonstrates techniques we can try and apply in our work. Even if we dress it up differently! For example, while we might not want to use many I-V relationships, we can certainly use texture and melodic fragmentation to develop our musical ideas, refreshing them for our listeners. In your next composition or arrangement, why not try counterpointing fragments of your melody in a small passage of your work? Why not use a texture you use less frequently at an important point in the work, perhaps the beginning, taking your listeners by surprise?

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

The Lark Ascending (Music Composition Analysis) – Ralph Vaughan Williams (Article 1 – Lessons in Harmony)

How to repeat melodies without them getting boring… [Video]

5 ways of Understanding woodwinds

Arabesque No. 1 – Claude Debussy (Music Composition Analysis)

Spiegel im Spiegel – Arvo Pärt

Salut D’amour – Edward Elgar (Music Composition Technique Analysis)

Sources (with links, where relevant)

Auke J2 (2012) Mozart Piano Sonata No. 8 in A-Minor KV. 310, Grigory Sokolov [Video].

Bartje Bartmans (2016) Mozart – Violin Sonata No. 21, E Minor, K. 304 [Szeryng/Habler] [Video].

Gay, P. (1999) Mozart. London: Phoenix.

Nagel, J. J. (2007) Melodies of the Mind: Mozart in 1778. American indigo 64(1), pp. 23-36.

Reitenga, B. (2011) A comparative analysis of the role of the violin in the sonatas of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, with special attention to the early sonata k. 304 and the late sonata K. 526. MA Thesis. Ball State University, Indiana.

1 thought on “Mozart’s E-Minor Violin Sonata, K. 304: music composition techniques”

Comments are closed.

Pingback: The Flag Parade - Music Composition Techniques - Any Old Music