There is plenty to learn in analysing a composition. In the previous article I analysed and discussed the arrangement of Bizet’s Farandole. Here I take the learning process one step further by experimenting with combining the classic nursery rhyme melody “London Bridge” with the arrangement of Farandole. Taking the structural breakdown that I presented in the previous article I apply similar textures, orchestration and melodic treatment to “London Bridge”. This article discusses my process, thinking and lessons learned in undertaking this learning experiment.

Share with friends?

Recapping

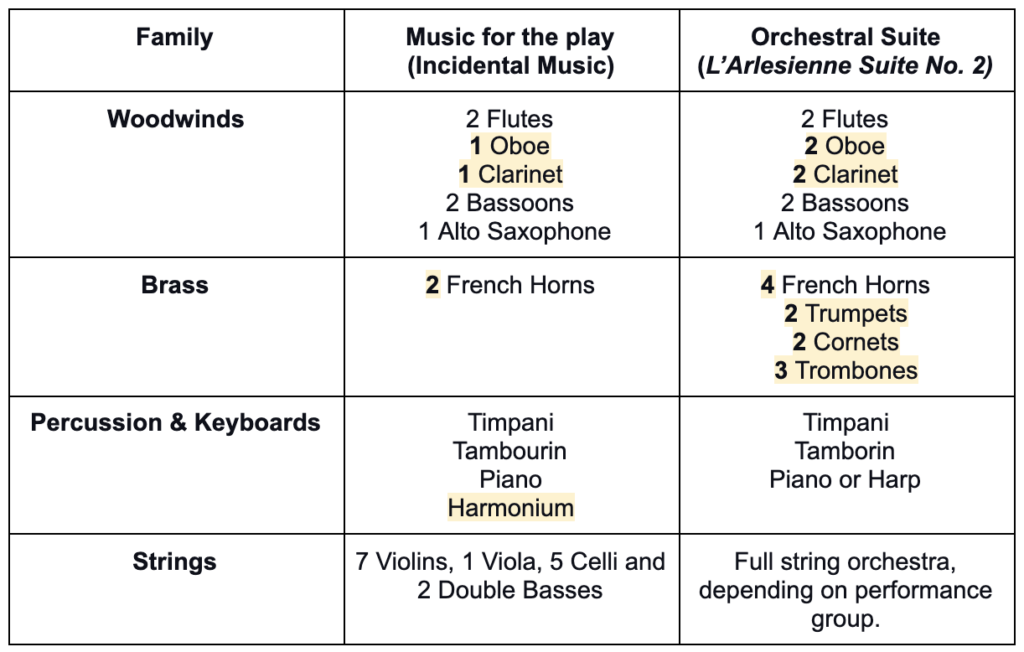

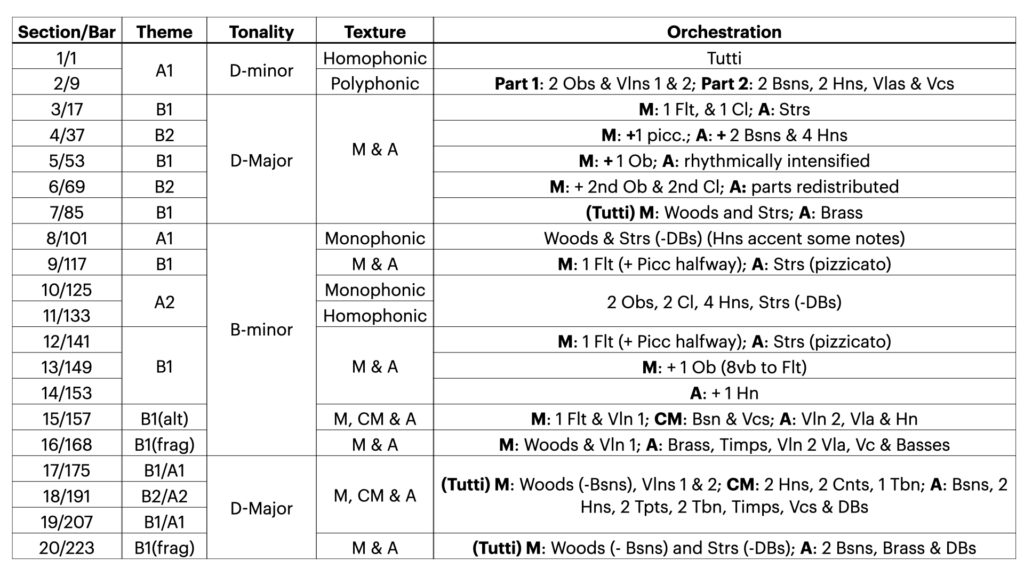

Before discussing the different aspects of my arrangement it is probably best to reprise the orchestral forces and structural overview of Farandole. Below I give the two tables highlighting each one.

Looking first at the orchestra, we can see it is a sizeable contingent. Modest by later-romantic standards it is much bigger than the orchestra used as part of the play, L’Arlesienne. It’s also bigger than the earlier orchestras used by composers such as Haydn and Mozart, due, primarily, to the growing prevalence and versatility of brass instruments in this period. The invention of valve systems enabled brass instruments to be chromatically tempered instruments as opposed to being limited to the overtone series relevant to their key.

The table above shows the difference between the two orchestra’s of the original composition and the arrangement of the suite. The Brass section is much larger in the suite.

Secondly, the structural overview of Farandole, created in the previous article, demonstrates a concise use of four themes. The melodic treatment of these themes is modest, relying on broader variations of tonality, texture and orchestration. to create variation. The table demonstrates a range of textures used, including homophony, polyphony and melody and accompaniment. The orchestration is often used to vary repetitions of themes or the repetitive alternation between two themes, by adding instruments gradually to each section. Tonally the work has a kind of ternary structure that is, broadly speaking, supported by the thematic material. Starting in D–first minor, then major–the work modulates to B-minor before reprising the themes in D-major. The effect of this is quite heroic, where earlier minor themes are transposed into an uplifting major tonality, reinforced by an orchestral tutti.

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Creating additional Melodic Material for London Bridge

In attempting to imitate Farandole, I realised I needed to compose extra material and start with the final section first. As we established in our analysis of Farandole, the melodic material was closely knit, with all the themes revealing their contrapuntal and linear relationship in the final section of the movement. To make sure the earlier material would work with the later material, I had to work backwards.

Similar to Farandole, the use of London Bridge is reflective of its use of the pre-existing carol La Marche de Rois. However, London Bridge is only 8-bars in length. Unlike La Marche de Rois, which comprises four 16 bar melodies, or a pair of 32 bar themes, depending on how you look at them. Therefore, I needed to repeat and create a second section to complement London Bridge. To do this, I used motifs and inversions to the contour of the first 8-bars to write a melody that was both different but feels connected.

Once I had established my two A melodies: A1 and A2, as I refer to them in my analysis of Farandole, I could write countermelodies to them both, giving me my B1 and B2 themes. To do this, I imitated the rhythmic features of Farandole. I did this primarily so that I could quickly imitate the small developmental periods in the piece where Guiraud alters, fragments and then liquidates the themes in the preparation of the climactic final section and the coda of the work. Opening the door to melodic developments of my own would likely have led to the piece losing its identity, diminishing the intended learning exercise. It was also revealing to see, through the imitation process, the effectiveness of subtle melodic variation both musically as a listener and as a creator, making the writing process much more manageable in a short space of time.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

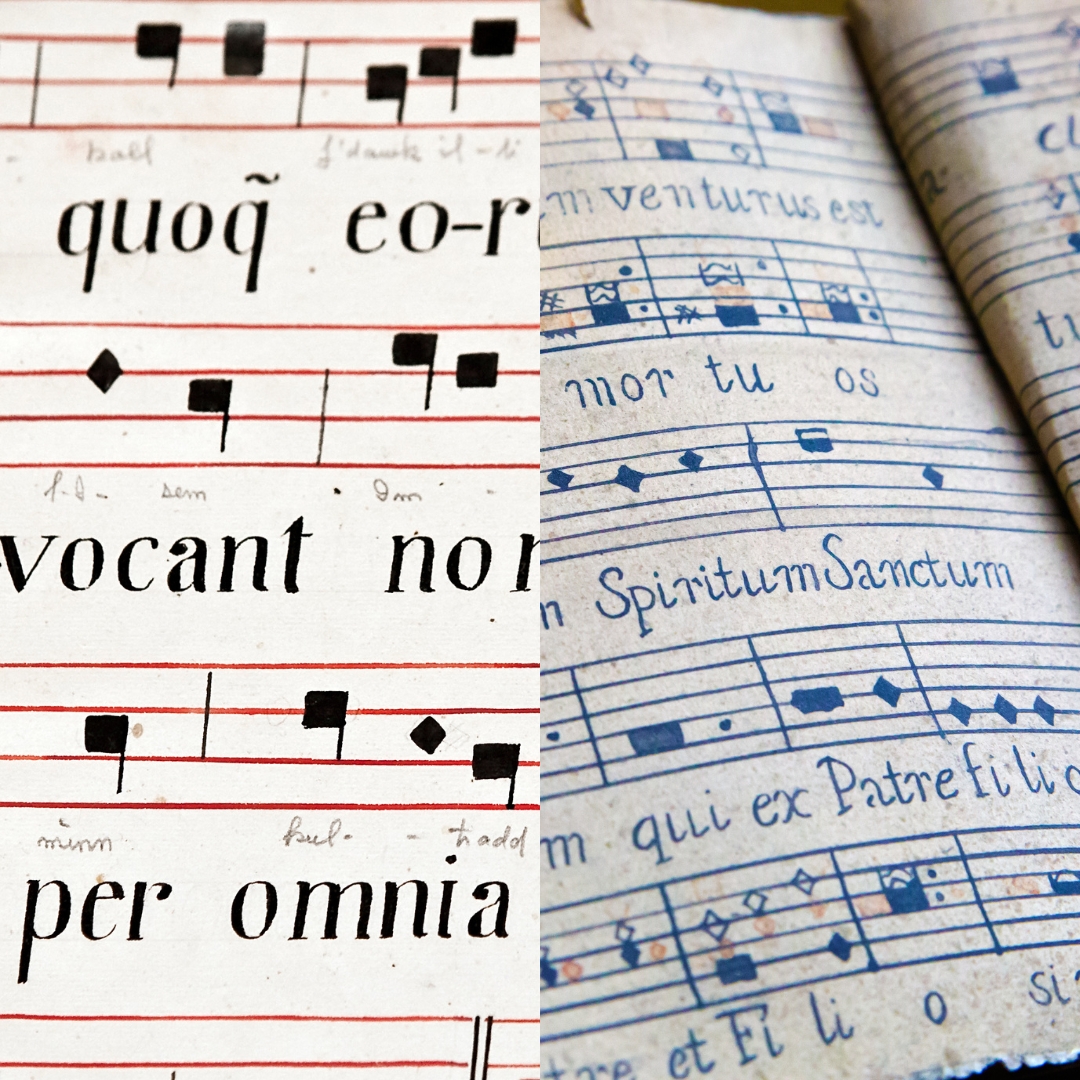

The themes of my London Bridge arrangement, laid out as they appear in counterpoint near the end of my arrangement. You can see my composed themes bare similarities to the themes from Farandole. This was so I could transplant things more easily for the experiment. I did not want to get bogged down in translation, for what was a learning exercise.

Arrangement: texture and orchestration

Once I had my material for the final section laid out, I then took the melodies and started to sketch material to match the textural schema that Farandole presents. Therefore, the introduction of my London Bridge arrangement uses both a homophonic, chordal texture and then a two-part canon. It was only in doing this that I realised that I neglect homophonic writing in my work. I cannot remember the last time I used a homophonic texture (which probably shows in my part writing!).

In exposing the B-themes, I then deploy a melody and accompaniment texture similar to Guiraud does in Farandole. I also copy the orchestration strategy that enables him to repeat the melodies over and over through this section: slowly building the intensity through the gradual addition of players. This kind of simple economy is something I often neglect in my orchestrations, so going through the process of imitating Guiraud’s orchestration was hugely insightful.

You can probably guess by now that I copy the textural plan and orchestration quite closely. I use the same monophonic, homophonic and melody and accompaniment textures; along with similar orchestral colours. I do this until the final section, where I add an extra counter-melody, so the texture becomes more polyphonic, especially with my decision to use a static, pedal harmony as the accompaniment component.

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Tonal schema and Harmony

I probably indulge myself the most in the final part of the work, building to a coda where I place more fragmented motifs of the London Bridge Melody than Guiraud does of La Marche de Rois. Another place where I was able to inject some of myself was in the harmony, where I use some modal mixture in the exposition of the B-themes. If I were to revise the piece, I think it would be here. Not to change the harmony, but to get more nitpicky about the voicing of individual chords, the voice-leading and its distribution across the string orchestra as divisi and non divisi.

Working to the same tonal schema as Guiraud was insightful as well. Using closely related keys as the primary modus of melodic development was an efficient means of quickly varying the melodies in a way that refreshes them from the listener’s perspective. Moreover, the larger scale minor to major switch of the London Bridge melody was again a simple but very expressive and effective device that could certainly have application in other arrangements. Particularly for the final movement of a multi-movement work or suite, where you might want to create a climactic moment similar to Farandole.

Before evaluating the wider, creative lessons learned from this process, it is probably worth now listening to my arrangement of London Bridge. In doing so, I have prepared a score to follow the music and an accompanying chart that highlights any deviations, in red, from Guiraud’s arrangement of Farandole. I use note performer to recreate the sounds here because I cannot afford an orchestra.

The Arrangement

Before summarising the lessons learned and having discussed my creative approach, its high time we heard my final arrangement of London Bridge! I use NotePerformer to produce the audio here. I’d recommend it to anyone who uses scoring software as part of their creative process. (I do not have affiliation.)

Reflection: Lessons Learned

In creating my version of London Bridge for Orchestra, I took my previous analysis of Farandole, as the basis for my arrangement tracing it very closely. It proved to be an incredibly fun learning exercise as I was able to create a complete piece of music quickly and pick up useful devices that I can apply in future, more freely and with greater originality. I want to summarise now, with three lessons I have learned from using Farandole to create my version of London Bridge.

The first of these lessons was the reaffirmation that musical ideas, or any ideas for that matter, do not come linearly and that we should not expect or believe that they do. To compose a piece similar to Farandole, I had to figure out the finale of my arrangement first. I had to compose a melody to London Bridge, that could work like the A2 theme extracted in my analysis of Farandole. I then had to compose counter-melodies to these melodies that could form the basis of my B1 and B2 themes. These materials could then be broken up and adapted in the wider arrangement, including earlier portions of the arrangement or composition. I had to start first with the ending and then go to the beginning.

The second lesson was that writing counter-melodies can be an efficient means of doubling down on your melodic material. Constrained by your first melody, it channels your creativity, as the creative problem is more defined: you need to create a counter-melody. If we think about Rennaissance polyphony for example, composers of this time used cantus firmi, which were pre-existing melodies, around which they could create their own polyphonic compositions. Using the rules of counterpoint, their freedom was restricted but their creativity was harnessed. In this instance we could also use the rules of counter-point or our subjective intuition, to determine whether the melodies sound “nice” together. Eitherway, the already existing theme gives us a creative heading.

The third lesson is that thinking sectionally, while, perhaps, a little more rudimentary, is a useful device for composing quickly. Thinking about the juxtaposition or adaptation of sections as opposed to the creation and adaptation of smaller musical units, like a motif, is inherently quicker, as you are reiterating portions of music that span more time. For instance, composing just two 16-bar sections of music, like in Farandole, and juxtaposing them in four different pairs of iterations, will give you 128-bars of music. Using subtle orchestration changes, again, like in Farandole, means that writing 128-bars of music will not have to take you very long either. What we create is not only under our control, but how we create it is as well.

In summary, reflecting generally on the exercise as a whole: I have found that simple infrequent developments, to larger portions of music, are not only easier to create but can be just as effective from the listener’s perspective. While I don’t think I am an uneconomical composer, as I do believe one of my strengths is to compose with few ideas. I do, however, think I tend to over compose with those few ideas and that can make me inefficient at times, as working out how to present the different permutations of those few ideas takes time. Essentially, the overarching lesson is one of strategy. As a composer, arranger or orchestrator, I need to think more about time:

If time is scarce and the musical requirements are larger, then make it easier for yourself and emphasise simple, large-scale permutations. If time is plentiful and the musical requirements are smaller, then challenge yourself and explore complex permutations on multiple levels of the composition. (Sage wisdom)

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Bibliography

Bizet, G. (1873) L’Arlésienne Suite No. 1 [Musical Score]. Paris: Choudens Père et Fils.

Britannica (2020) Farandole: dance.

Britannica (2020) L’Arlésienne: incidental music.

Dahlhaus, C. (1989) Nineteenth-Century Music. Translated from German by J. B. Robinson.London: University of California Press.

Grove Music Online (2001) Bizet, Georges (Alexandre-César-Léopold).

Grove Music Online (2001) Farandole.

Grove Music Online (2001) Guiraud, Ernest.

Latham, A. (ed.) (2002) The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia (2020) La marche des rois.