During the first and third UK lockdowns, my friends and I used the Civilisation games as a way of meeting up virtually. Without fail, each time we play Civ VI, at least one of us will sing or hum the main theme, Sogno di Volare, into our headsets. For this reason, I thought it would be a great piece to look at, especially as I was able to gain access to the orchestral score via nkoda (no affiliation).

In looking at the piece, I found many insightful concepts and techniques of composition. I want to share these techniques and concepts with you here. To summarise and give you a flavour of what to expect:

- Tin uses a form very similar to the Rondo, identifiable via the order and repetition of lyrics and themes.

- He uses several themes that are tightly knit, creating both consistency and variation.

- There are several interesting harmonic devices: polarity, pattern, sequence and modulation.

- Deliberate or coincidental, there are many structural relationships and consistencies between the main ostinati, themes and harmony/tonality of the composition.

Context

Two-time Grammy award-winning composer, Christopher Tin, is the composer of, Sogno di Volare. Baba Yetu, the main title for Civilisation IV written by Tin, was the first piece of video-game music to be awarded a Grammy.

In 2016, Tin was commissioned to compose a new main theme for the upcoming instalment of Civilisation VI. Sogno di Volare is his response to this commission. Using an original text by Chiara Cortez, inspired by the writings of Leonardo da Vinci. According to the Civilisation wiki, one of the quotations that inspired the lyrics for Sogno di Volare, appears in the game. It is read by Sean Bean when you discover flight (a recording can be found on this Civ wiki page):

“For once you have tasted flight you will walk the earth with your eyes turned skywards, for there you have been and there you will long to return.”

– Leonardo da Vinci

A common pattern emerges in Tin’s work, which sees him occupy a unique position that straddles video-games and concert halls, a foot placed in each sphere. In 2020, he released his album To Shiver the Sky. Sogno di Volare appears as the first track in the album. Similarly, Tin composed and produced a song-cycle, Calling All Dawns between 2009 and 2014, reusing Baba Yetu. Creating works that delight video-gamers, he builds on them, accessing that community and developing his niche audience, by producing stand-alone compositions of a similar ilk. A strategy that works, it is great to see the use of orchestras and orchestral music garnering such popularity.

Entirely coincidental, Tin also happens to be running a Kickstarter for an upcoming project. If you’re a fan of his music, you might want to check it out. Or, if you become a fan of his music by the end of this article you might also like to check it out. I’ll put a link in the summary section too.

Rondo, text, rondo, theme, rondo, ostinati & rondo

Text & structure

Sogno di volare is, loosely, in rondo form. Its design can be defined as follows: A A B A1 C B1 A. The reoccurrence of the A-section between multiple, different sections makes this a rondo composition.

One can identify this schema in two ways:

- by the use of the lyrics

- by the use of the themes

To demonstrate these two points, we can colour code the lyrics. Doing so allows us to see repetitions more easily. For example, the verses in black are the A-sections of the rondo form. As you can see, there are multiple stanzas in black, and in between these stanzas is text in other colours. The green and blue text highlight the use of theme 2. Specifically, the blue colour distinguishes a sequential passage that bridges into and prepares the return of A-sections (I discuss this sequential passage later). The red text defines the use of a 3rd theme, which is labelled as C. Colour coding the text in this way, clearly demonstrates the compact, rondo form of the work.

(The numbers relate to colour coding and ex.3, column: “text” and “Theme”, as text and theme are paired)

(1)

Una volta che avrai

Once you have taken flight

Spiccato il volo, deciderai

You’ll decide

Sguardo verso il ciel saprai

Gaze towards the sky, you’ll know that

Lì a casa il cuore sentirai

That is where your heart will feel at home.

(1)

Una volta che avrai

Once you have taken flight

Spiccato il volo, deciderai

You’ll decide

Sguardo verso il ciel saprai

Gaze towards the sky, you’ll know that

Lì a casa il cuore sentirai

That is where your heart will feel at home.

(2)

Prenderà il primo volo

The great bird

Verso il sole il grande uccello

Will take his first flight toward the sun

Sorvolando il grande Monte Ceceri

Sweeping over the great Mount Ceceri

Rimpendo l’universo di stupore e gloria

Filling the universe with wonder and glory.

(1)

Una volta che avrai spiccato il volo, (slight variation in text and treatment)

Once you have taken flight

Allora deciderai

You’ll decide

Sguardo verso il ciel saprai

Gaze towards the sky, you’ll know that

Lì a casa il cuore sentirai

That is where your heart will feel at home.

(3)

L’uomo verràportato dalla sua creazione

Man will be lifted by his own creation

Come gli uccelli, verso il cielo…

Just like birds, towards the sky…

(2)

Ohh… (Uses brief thematic segment of earlier “Prenderà il primo…” verse)

Ohh…

Rimpendo l’universo di stupore e gloria

Filling the universe with wonder and glory.

(1)

Una volta che avrai

Once you have taken flight

Spiccato il volo, deciderai

You’ll decide

Sguardo verso il ciel saprai

Gaze towards the sky, you’ll know that

Lì la casa il cuore sentirai

That is where your heart will feel at home.

Gloria!

Glory!

Theme & Structure

The thematic material of Sogno di Volare, is compact. While it uses three different themes, in a relatively short piece, they boast motivic similarities. These similarities make the composition feel concise and unified.

Each of the three themes can be paired with a portion of the colour coded text. Firstly, theme 1 with stanzas in black. Secondly, theme 2 with stanzas in blue and green (the distinction of these will be discussed later). Thirdly, the stanza in red is theme 3. Therefore, if the lyrics were omitted for whatever reason, the thematic material would also communicate the structure of the work.

If we extract the three themes, it is much easier to see their motivic consistencies. For example, in the extracts below, I have highlighted the persistent use of certain intervals. The consistent use of intervals is significant, as it imbues each of the themes with similar characteristics. Furthermore, some of these intervals relate, as we will see, to other components of the work.

The first example (ex.1) demonstrates the use of unison (red boxes) and minor-2nd (blue boxes) intervals in each of the themes. While less prominent, I think their use is noteworthy due to their position within each theme. The use of unison and minor-2nd steps occur, predominantly, at the start of each melody. The first set of intervals we hear, at the statement of each one, their importance is elevated.

In the case of the 2nd theme, we have to accept the unison as being similar to the octave. But this reveals a simple way of varying the theme by maintaining pitch content but altering intervallic character. Subtle, it creates measured variation where we can both appreciate the difference and similarity.

Similarly, the unison and minor-2nd in the 3rd melody line bind it to the 1st. While theme-3 is Rhythmically augmented, the interval patterns for the first four notes are the same in both melodies: unison, unison, unison, down a minor-2nd. Again, like the variation of the 2nd theme, the augmentation brings freshness, while the intervallic similarities maintain consistency.

Ex.2 reveals some insightful intervallic consistencies and qualities across larger portions of each theme. The most significant is the perfect-4th, which appears as the span of many phrases and segments of each melody. Prominent in theme 1, one can see (in the yellow boxes) how these segments outline or do not extend beyond the span of a perfect-4th.

The use of the 3rd intervals, similar to perfect-4ths, is less significant regarding melody and motif. Instead, all of the intervals in this extract become more important when evaluating harmony and tonality. Hence my annotation of them in ex.2. The 3rd, as we will see, is a notable interval that permeates the work on a larger scale, along with the perfect-4th.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

How does John Williams create such compelling melodies? Let’s find out.

Ostinati

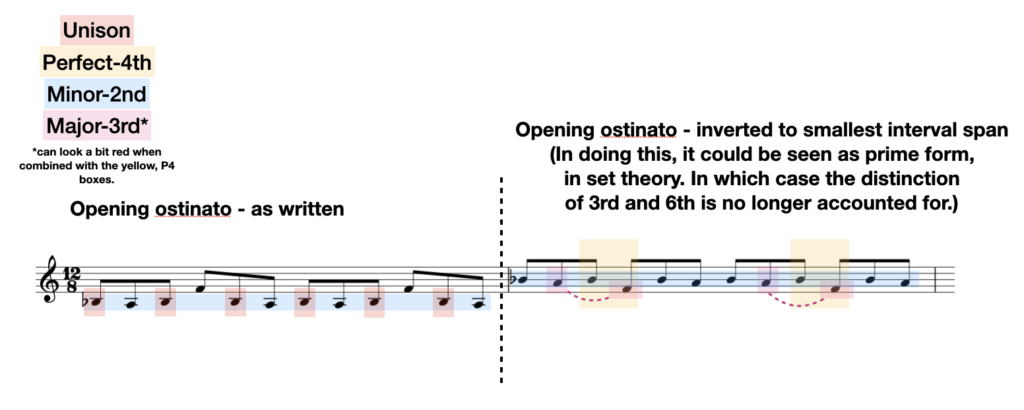

I want to briefly touch on the ostinati, which are probably deserving of more attention here. Only, I have to delineate areas of focus to avoid convolution. However, linking to the themes, which the ostinati are themselves, almost, in places. Veiled by inversion, one can identify 3rd and 4th (mediant/sub-mediant & sub-dominant/dominant) relationships in the opening, main, ostinato.

If we extract the main ostinato (ex.3), for instance, we can see it spans a minor-6th. Containing Bb, A and F, if we raise the Bb and A by an octave, the intervals begin to outline some commonalities with the thematic material. Namely, the 3rd and perfect-4th.

In ex.3, I have made annotations of the ostinati, highlighting important intervallic relationships. These are presented in the form of the original ostinati, as it appears in Sogno di Volare, and a transposed version.

Two of the relationships presented by the annotations are significant with regards to the themes. The unison and minor-2nd, as we have established, are present within each of the thematic materials. This relationship is meaningful as it highlights a degree of motivic similarity between the theme and the ostinato that frequently accompanies it. Rather than having a distinct ostinato and melody part, the intervallic similarities bind them together. Furthermore, these intervals emerge regardless of transposition.

The effect of these similarities will be an increased sense of unity as the constituent parts–ostinato and theme–work together rather than counterpoint each other.

In looking at the transposed version of the ostinato, we can also see some other vital relationships. These relationships are also significant when considering the themes, but have salience when looking at the tonal schema and harmony. For example, in transposing the ostinato (the second bar of the extract), the intervallic span becomes a perfect-4th. Furthermore, the minor-6th, between A and F, becomes a major-3rd. As we will see, sub-dominant and mediant relationship/polarities are endemic in the work’s harmony and tonality.

Harmonic polarities, sequences and arcing tonal structure

Tonal Schema

Despite being a rondo form, the underlying tonal schema of Sogno di Volare takes a different trajectory. Starting and ending in Bb-major, the work passes through a handful of other keys. One might anticipate that, within the rondo form, Bb-major would return when the A-section does. It does not. In avoiding Bb-major, through the middle section, its eventual return is made more gratifying.

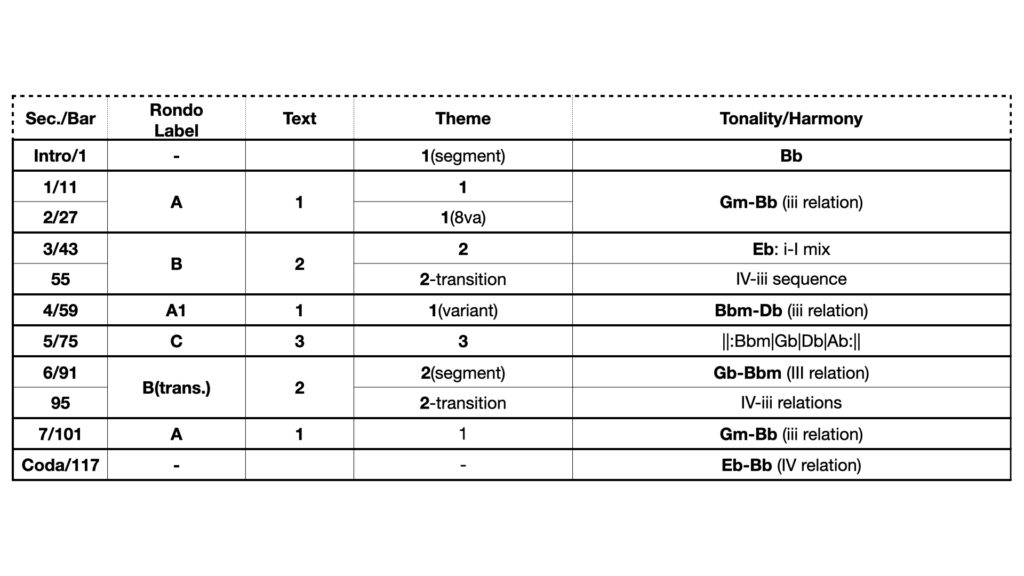

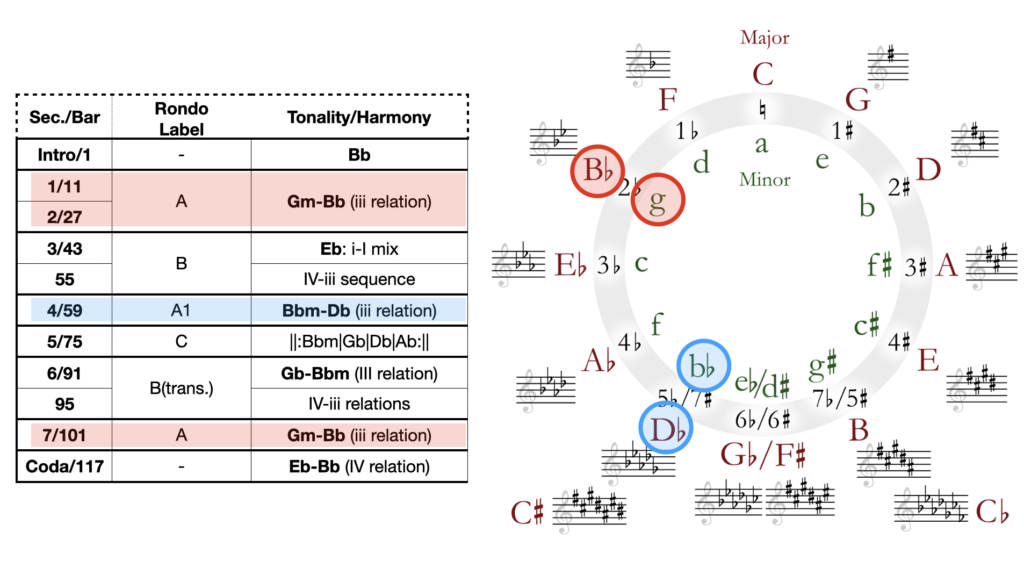

Ex.4 presents a structural breakdown of the work. In demonstrating the tonal schema, it also highlights components that we have discussed already. For example, the “rondo label” column shows how we might label the sections of the work analytically. The “text” column relates to the earlier colour coding of the text. The “theme” column relates to the previous analysis, offering additional details on their variation (where relevant). Laying out the overall structure of the work in this way is valuable, as it lets us see what structures correspond with others. Or which structures take a different trajectory, like tonality in this instance.

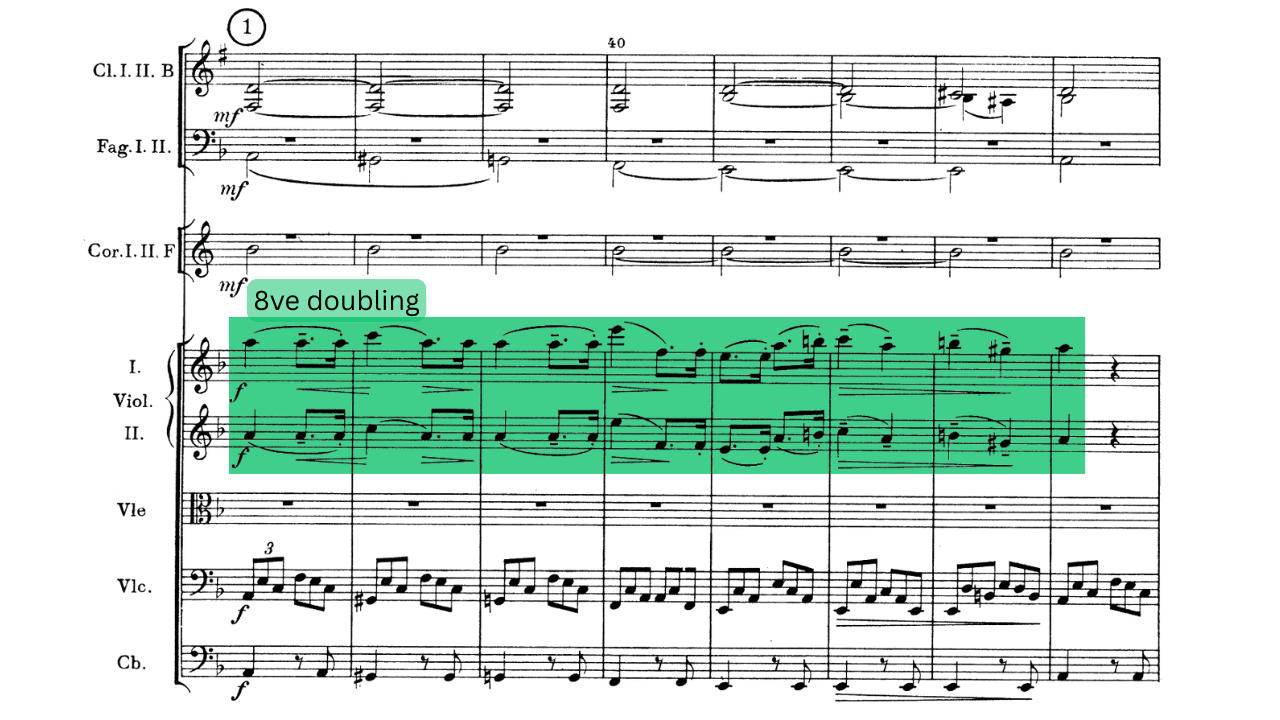

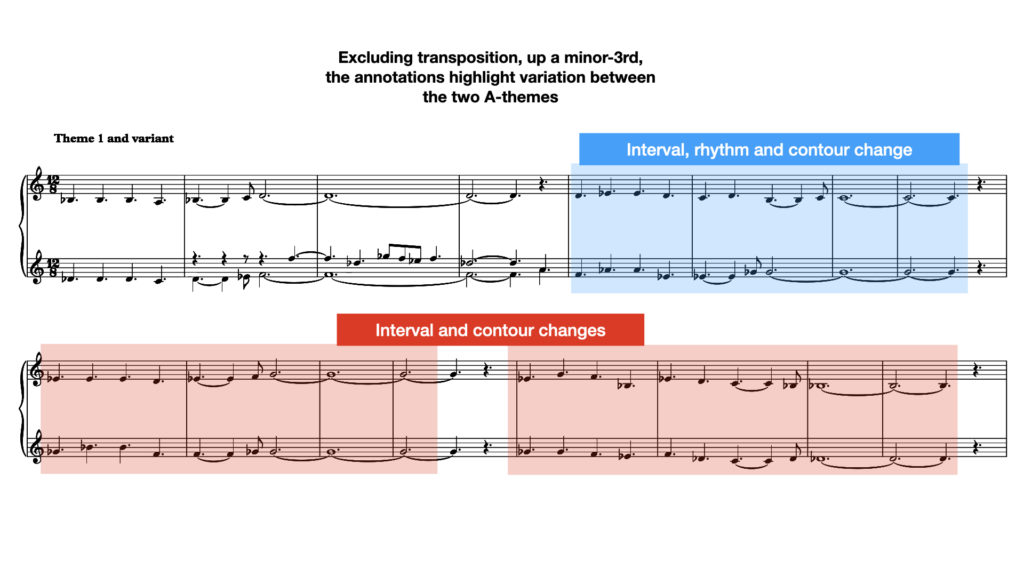

Similar to how John Williams uses straight transpositions of melodies in The Flag Parade theme, Tin also transposes his A-theme into a new key at 4/59. However, as can be seen in ex.5, he varies other parameters of the A-theme. For example, in bar 5 of the extract, the contour is similar, but the intervals move by skip rather than step. In bar 6, the rhythm, contour and intervals are different. These changes provide more variation than a straight transposition.

Harmonic/Tonal Polarity

Sogno di Volare sets up mediant and sub-dominant polarities. The mediant relationships, in part, occur between relative major and minor keys. Something that I discuss in the following section, on a smaller scale, I want to discuss larger scale relationships here.

On a larger scale, one can see mediant relationships between the sections. Section 1 is in Bb-major/G-minor (more the former). When the same theme reappears in section 4, the key is now Db-major/Bb-major, a minor-3rd/chromatic-mediant relationship with Bb. Likewise, in section 6, where we hear theme-3, the key is Bb-minor/Gb-major. Gb-major is a minor-6th/chromatic-sub-mediant relationship with Bb.

Again, like John Williams’ The Flag Parade, we have mediant and parallel relationships between sections. However, Tin also builds larger-scale sub-dominant relationships, not too dissimilar to what we might expect in a classical work, like Mozart, for instance.

In section 3, the second theme tonicises Eb. However, in harmonising the second theme, Tin sets up interesting polarities between Bb-minor and Eb-minor, and Ab and Eb. A pair of sub-dominant relationships. For example, if we extract the harmony, the second section uses the following progression:

(The | delineates the phrase ends.)

Bbm – Ab – Ebm – Bbm | Fm – Eb – Bbm – Eb | Ebm – Bbm – Ab – Eb ||

Or, in Eb:

v – IV – i – v | ii – I – v – I | i – v – IV – I ||

Arguably a string of dominants, when you lay them out as Bb – Eb – Ab, the tonicisation of Eb draws out the sub-dominant relationships between Eb-Ab and Bbm-Ebm.

Building on this, the harmonisation of theme-3 makes the emphasis on sub-dominant importance undeniable. If we do the same symbolic reduction of the harmony, this is what the progression looks like in section-6/bar-91:

(Each chord occupies two-bars, slowing down the harmonic rhythm. With the augmented theme, it is like we’re dreaming of flight or something… it’s like we’re birds heading toward the sky [Come gli uccelli, verso il cielo.])

||: Bbm – Gb – Db – Ab :||

Essentially, the entire chord sequence of section-6, which repeats, is a string of sub-dominants.

Finally, to round off this section, the work ends with a plagal cadence: Eb – B or IV – I.

Late in 1932, Sergei Prokofiev was approached by the Saint Petersburg (formerly Leningrad) based film studio Belgoskino Studios and commissioned to score

Harmonic Polarity/Substitution

I have not completed a roman numeral analysis of Sogno di Volare. (I do not enjoy doing them.) However, Tin seems to alternate between more functional and sequential harmonic passages.

In using more functional harmonies, Tin substitutes chords that impose tonal polarities via diatonic or chromatic/modal means. For example, in the opening harmonisation of section 1, theme 1 (bar 11), the progression is Gm(vi) – Eb(IV) – F(V) – Bb(I).

Highly functional (IV[sub-dom]-V[dom]-I[tonic]; perfect cadence…), the Gm or vi, in the above instance, is a simple substitution. vi and iii are subtle but nice substitutions for I, if you want to add some colour to your melody lines, within functional modes of harmony.

The above pattern appears again in section-4, in Db-major, reprising theme 1. I found this a significant creative choice. So much so, I’ve decided to define it as a harmonic polarity between major and relative minor. The major key, is, without doubt, the tonic in these sections. (Being firmly tonicised by the use of V-I progressions.) In this sense, I think the polarity is not on equal terms but present through repetition. Furthermore, other polarities/relationships emerge in patterns and sequences, relating to interesting larger-scale relationships (iii/mediant and IV/sub-dominant) that we will discuss next.

Harmonic Polarity/Sequence

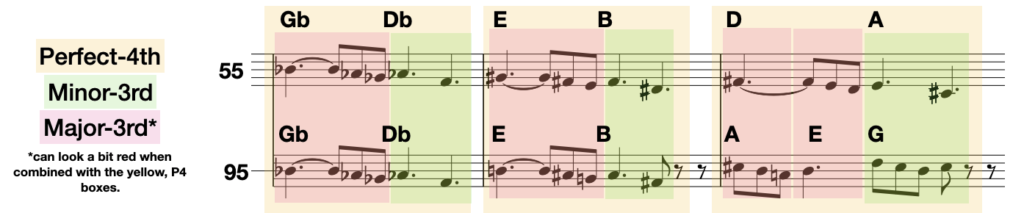

Ex.6, in the previous section, highlights the relative major-minor relationship in each of the A-sections. However, it also highlights the relationship of a mediant/3rd between these sections too. This mediant relationship holds significance in the bridge/transition sequence (highlighted as blue in the textual colour-coding).

If we extract each of these sequences (ex.7; bar 55 and 95) and reduce them to chord symbols (to identify chord) and [bracketed] Roman numerals (to highlight harmonic relationship), we can see an emphasis on iii. (I use enharmonics in bar 55 and 95. Otherwise, the theoretical, intervallic relationship would not make sense here.)

Bar 55: F#[IV]C# |[iii]| E[IV]B |[iii]| D[IV]A

Bar 95: F#[IV]C# |[iii]| E[IV]Bmaj7 |[II]| A[IV]E[VI]G

(Some chords use inversions and extensions. I decided to omit them here, for visual clarity.)

These sequential passages are interesting as they further emphasise 3rd and 4th relationships. Now, I’m not suggesting that this was Tin’s thinking when writing the bridge section (nor any section for that matter. There’s a difference between composition and analysis). Although he has said that he views structural relationships as pertinent to his compositional aesthetic, seconded only by melody (Gamasutra, 2009). I think it’s much more likely, that the harmony emerged through voice leading rather than imposing a sequential framework harmonic framework in this small section. Then again, it is not impossible.

Summary

In summary, there is a lot to learn from this compact orchestral composition. For video-game, the structures and language it uses are by no means new. However, that should not be taken negatively and is not intended to be. Instead, Tin cultivates interest and sophistication through the structures and language he uses, creating a piece that measures its complexities. In other words, the nuance is in the exploration and exploitation of combinations.

In this nuance, we can take several lessons for ourselves as music makers:

- Simple forms bring clarity and accessibility

- Using small motifs, we can create large-scale unity

- Simple harmonic structures placed in meaningful small and large-scale combinations can lead to compelling relationships.

The promised second link to Tin’s The Lost Bird’s Kickstarter.

Morning Mood Analysis: How Grieg Turns One Idea into Endless Music A Composer’s Guide to Morning Mood Analysis Edvard Grieg’s “Morning Mood” …

This article explains how to orchestrate a melody by reducing orchestration to six fundamental approaches, helping composers make clearer and more deliberate decisions.

O Little Town of Bethlehem looks simple on the page, but it isn’t simplistic. In this analysis of the Forest Green version, I explore how Vaughan Williams creates shape, contrast, and finality using a remarkably restrained harmonic palette, showing how small details in form, cadence, and line carry real expressive weight.

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …