Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections for detailed analysis. I will choose these pieces based on what grabs my attention while listening. Once I find an interesting moment, I isolate it and explore why it stands out to me, sharing my findings here.

In this first entry, we will examine a few key moments from Francis Poulenc’s ballet Les Biches (1923). Specifically, I’ll focus on Rehearsal Mark 25 from the concert suite (a score can be found here; and a score video here), where Poulenc uses colorful orchestration and a clever modal interchange from F major to F minor. Before diving into that, it’s helpful to know more about Poulenc and his ballet Les Biches.

About the Composer and About the Work

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) was a French composer and pianist who blended classical and popular music styles. Born into a wealthy Parisian family, Poulenc was mostly self-taught, studying piano with Ricardo Viñes and composition with Charles Koechlin. He gained fame at 18 with his first work, Rapsodie nègre (here is a splendidly concise article on Rapsodie nègre). A member of the composer group Les Six, his early music was lively and witty, while his later works, especially his religious music, took on a more serious tone. Some of his notable pieces include Dialogues des Carmélites and Gloria. Poulenc’s music is celebrated for its strong melodies and emotional depth.

Les Biches (1923)

Poulenc’s ballet Les Biches was composed in 1923 for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and premiered in Monte Carlo in 1924. Choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska, with sets by Marie Laurencin, it is a plotless ballet focusing on playful, flirtatious interactions between men and women. The music mixes neoclassical forms with modern touches like jazz and parody. Lighthearted, Les Biches captures the carefree spirit of the roaring 20s and specifically 1920s Paris. The ballet was a major success and remains one of Poulenc’s best-known works. It continues to be performed by ballet companies around the world today.

Extra sources on Les Biches:

- https://massreview.org/node/10344

- The score also contains an English translation of the programme notes: https://imslp.org/wiki/Les_biches,_FP_36_(Poulenc,_Francis)

The Extract

Today’s extract comes from the first movement of the concert suite for Les Biches. The Les Biches suite is a selection of music from the ballet, arranged for concert performance. The first movement is titled Rondeau and relates to the musical form known as a rondo, where there is a principal theme typically labelled A in analysis. This A theme alternates with different themes, usually labeled B, C, etc. The form can be represented as ABACADA, and so on.

However, after listening and score reading the concert suite version of this movement, I noticed the structure feels more like a ternary form. The use of ternary structure could be unique to the concert suite, possibly rearranged. Or, it might be a nod to the Rondeaus written by 18th-century French composers like Lully, Couperin, and Rameau, who often used either rondo or ternary forms. Neo-classical and neo-baroque styles, which were popular in the 1920s, may have influenced Poulenc here. Although this is speculative, one or more of these factors could explain Poulenc’s choice of form in Les Biches.

Alternatively, the alternation of themes on a smaller scale than what I have analyzed might reveal a rondo form. For example, there is more than one theme per section of what I identified as ternary form. In something like a sonata rondo (though I’m not suggesting this is one), a B theme can also be recapitulated. So, upon closer investigation, one could potentially identify a form like ABACADA(CA)BA, or something similar. It is not the aim of these musical moments analyses to decipher form.

The specific passage we’ll focus on comes from the A section of the Rondeau, at rehearsal marks 25 and 26. We’ll look at this moment in detail, but note that it returns later with fuller orchestration in the recapitulating A section at rehearsal mark 37, near the end.

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

Score Video (Should begin at/just before rehearsal mark 25)

The Analysis

To begin our analysis, we’ll first look at the melody, followed by the harmony, and finally, the orchestration.

Melody

Melodic Structure

The melody at rehearsal mark 25 is simple, consisting of a 4-bar structure that can be broken down into two and then four parts. In two parts we can think of the structure of the melody as A and B, breaking the melody into two bar phrases. However, if we break it down into cells, we can spot and annotate the melody with the following arrangement of ideas:

- Bar 1 as a.

- Bar 2 as a’, a variant of a.

- Bar 3 as b.

- Bar 4 as b’, a variant of b.

In other words, bar 2 is a variation of bar 1, which together act as an antecedent idea. The repeated a idea is contrasted and completed by the b and b’ ideas in bars 3 and 4, which rounds off the 4-bar phrase as the consequent.

At rehearsal mark 26 (bar 5-8 in the image below), the melody is largely repeated but recast in the parallel minor. The only change beyond pitch is to the part of the melody we have labelled B’. Specifically, in recasting the B’ part of the melody into a minor key, Poulenc transposes parts of the cell we can label b’’ and then quite distinctively adapts b’’’, bringing the whole section to a close on minim beat 2 of the final bar of the extract. We’ll examine the harmonic shift more closely when we discuss the harmony in the next section.

Motif Breakdown

If we break the melody down further into motifs, we could identify a and a’ in bars 1-2 as containing two distinct motifs that form the cell a and characterise the wider phrase we have labelled A. The first minim beat (the repeated quavers) forms motif z, while the semiquaver turn-like figure followed by two quavers becomes motif y. In the b cells, motif x consists of the dotted crotchet and quaver in bar 3, which is elaborated on in bar 4 (x’). Motif w is the three descending stepwise quavers, transposed up a fourth from bar 3 (minim beat 2) into bar 4 (minim beat 2).

Below is an analysis of the motifs in the theme, as I understand them. The apostrophes are used to simply denote the link between motifs, cells and phrases, with the letter corresponding to a group of motifs, cells and phrases. The depth of analysis here might seem a bit heavy, but it will help us dive deeper into the orchestration soon. It also highlights how tightly constructed the music is, at least in this moment of the ballet.

Harmony

Before we move on to the orchestration, let’s take a quick look at the harmony. Surprisingly, for an early 20th-century piece, the harmonic language here is incredibly simple. It seems to nod to neo-classical styles. Roman numerals can easily be applied, revealing a highly functional progression: I - V65 - V7 - I, on every minim beat of the first two bars.

In the key of F major, this progression starts on the tonic (F major), moves to a C dominant 7th in first inversion over E, then resolves to a C dominant 7th in root position, finishing with a perfect cadence on F major. This same progression is repeated in bars 3 and 4 under the b section of the melody.

Harmonic Shift at Rehearsal Mark 26

At rehearsal mark 26, the melody and harmony are almost identical but with one key difference: the mode changes from F major to F minor. This results in a few alterations, particularly to the leading tone (E). While E remains to form the dominant 7th chord (which stays the same in both major and minor tonalities), the 4th scale degree (B♭) is raised to B-natural in the semiquaver figures of motif y and y’.

The harmonic progression remains i - V65 - V7 - i, but the change to the tonic in the minor mode is notable. Essentially, Poulenc performs a modulation to the parallel minor, or what we might refer to as a modal interchange, shifting from F major to F minor while keeping the tonic the same but transforming the pitches around it.

Modal Interchange vs. Modulation

Is this shift a simple modal interchange, or does it represent a true modulation? If Poulenc had shifted from F Ionian (F major) to F Aeolian, modal interchange would be a clear explanation. However, the use of a dominant 7th chord (rather than a minor dominant, which is expected in F Aeolian or natural minor) suggests a deeper tonal shift. The extract’s harmony raises the question: is a major to minor shift a change in tonality or modality if the tonic remains constant?

There may be more in-depth theoretical discussions or papers on this topic that I simply have not encountered. But in essence, the shift from major to minor could be interpreted as both tonal and modal depending on how we think about it.

Summary of Harmony: Modal/Tonal Shift

Regardless of whether we call it modal interchange or modulation, Poulenc simply recasts the same idea with slight alterations, moving from F major to F harmonic minor. This shift is what caught my attention and inspired me to choose this section—and this piece—for the first entry in the Musical Moments series.

Now, let’s dive into the orchestration!

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

3 lessons from arranging London Bridge for orchestra

Making Mozart Scary

The Lark Ascending (Music Composition Analysis) – Ralph Vaughan Williams (Article 1 – Lessons in Harmony)

Aaron Copland – “Simple Gifts” (Appalachian Spring / Ballet for Martha) – Bitesize Music Composition Analysis

The Day the Earth Stood Still, Bernard Herrmann – Orchestration Technique

Orchestration

Instrumentation Overview

From a large orchestra that includes piccolo, flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, trombones, and more, Poulenc limits his orchestration in this section. He uses just 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 1st and 3rd horn, and the string orchestra.

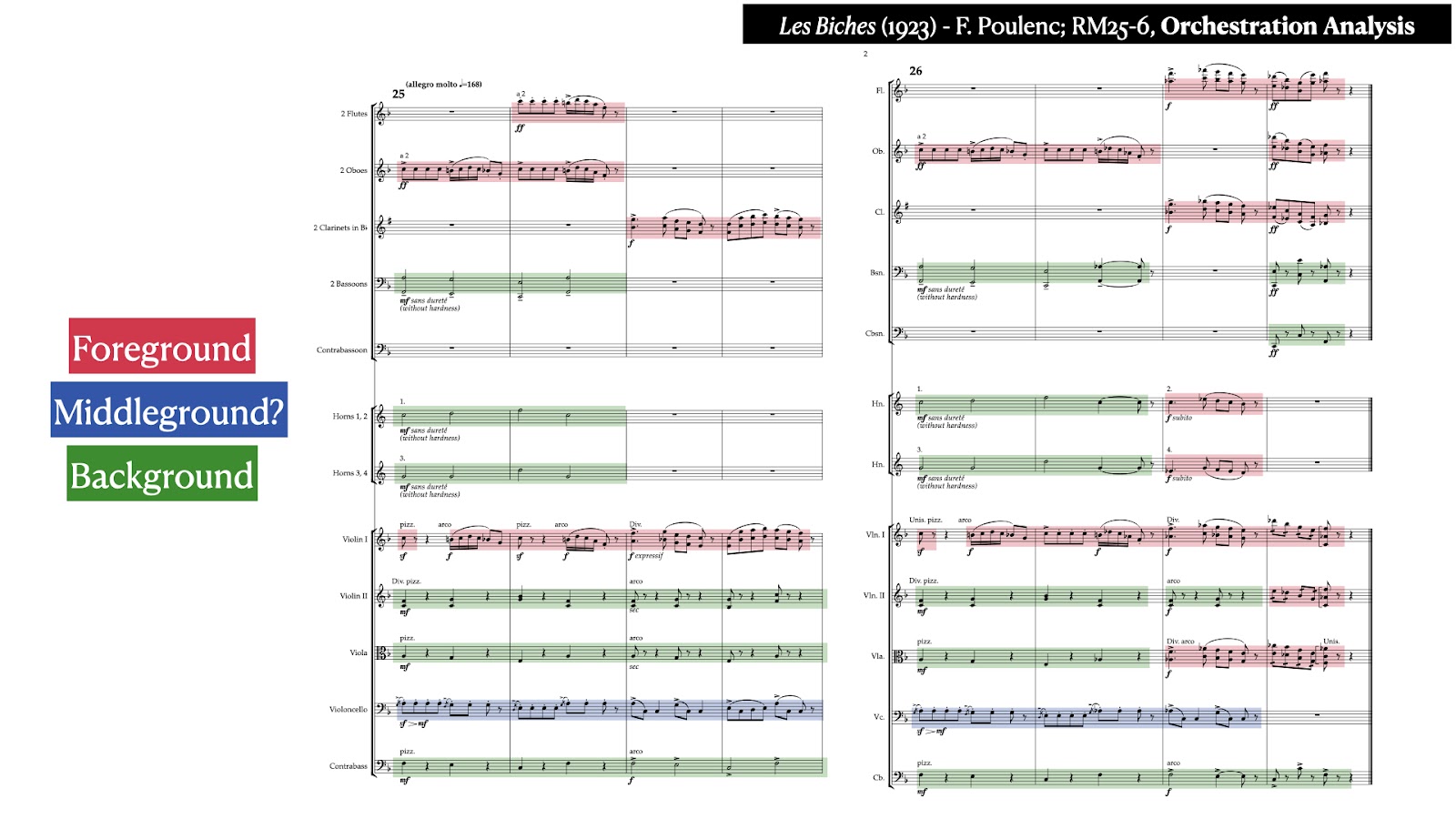

Orchestration Layers

In this passage, there are three main orchestration layers:

- Foreground (Melody): Presented mainly by the oboes, violins, and clarinets, with various exchanges between instruments.

- Middleground: Created by the cellos, primarily built on the z motif from the melody.

- Background: A simple block chord progression, presented by pizzicato strings (2nd violins, viola, and double basses), 2 horns, and 2 bassoons.

Foreground - Melody

Foreground - Melody

The melody, or foreground, is vibrantly orchestrated. The a and a’ motifs are given to the 2 oboes in unison. The violins double the y-motif of bot a cells at the unison. And, in the a’ cell, the oboes are doubled by the flutes an octave above. In this same cell after rehearsal mark 26, the violins double the oboes at the unison.

The b cells are played by the 2 clarinets in 6ths, along with divided 1st violins. After rehearsal mark 26, when the b cells are repeated divided violas (an octave below), 2 divided flutes (an octave above), and 1st violins at the unison join in. Horns 2 and 4 add weight by doubling the clarinets an octave below (in unison with the violas) three bars after rehearsal mark 26 only, while oboes double the flutes at the unison (1 octave above the clarinets) four bars after rehearsal mark 26 to complete the section.

Middleground

The middleground, though largely harmonic, mainly consists of the y motif from the melody when counterpointing the a cells. It becomes more independent while counterpointing the b cells. The cellos, which dominate this layer, remain alone throughout, switching between performing as a supporting line to the foreground (a cells) and middleground (b cells) element.

Background Texture

The background is simple yet effective, providing harmonic support in block chords. Under the a motif, from the bass up, the lowest root note is played by the 2nd bassoon and pizzicato double basses in unison. The next line up features the 1st bassoon doubled by pizzicato violas. Above them, the two horns double the divided 2nd violins, also pizzicato.

Under the b motif, the bassoons and horns drop out, and the strings shift from pizzicato to arco. The violas and 2nd violins continue playing short quaver notes, while the double bass switches to accented minims, raising the dynamics from mezzo forte to forte.

Background Texture at Rehearsal Mark 26

At rehearsal mark 26, the orchestration remains consistent under the a motif, despite the shift to F minor. The b motif orchestration also stays similar, with the bassoons and horns dropping out and the strings transitioning to bowing. However, four bars after rehearsal mark 26, there’s an increase in weight to round of the section. The contrabassoon joins, doubling the double basses an octave lower, while the bassoons double the double basses at the unison (2nd bassoon) and a 10th above (1st bassoon).

Summary: Colourful Orchestration

With subtle instrument changes, shifts in technique, and dynamic adjustments, this section’s orchestration is remarkably colorful. Poulenc often begins with a base colour, like oboes or clarinets, then adds or subtracts instruments to shade different motifs and cells. In a neo-classicist approach, he reveals the form of his composition while using the vibrant palette available to the early 20th-century orchestra.

Conclusion

In this deep dive into Francis Poulenc's Les Biches, we’ve explored how this ballet blends neo-classical and modern elements, while also making clever use of form and orchestration. The selected passage, Rehearsal Mark 25 and 26, showcases Poulenc’s skill in manipulating simple harmonic progressions, modulating from F major to F minor, and utilising a wide range of colours through orchestration. His approach, while straightforward on the surface, reveals a carefully constructed balance between melodic motifs, harmonic clarity, and subtle instrumental layering.

Through shifts in dynamics, orchestration techniques, and the interaction between foreground, middleground, and background textures, Poulenc creates a vibrant and engaging sound world. The playful yet refined nature of this section is a hallmark of his style, merging wit with sophistication. Les Biches is an exhilarating composition and reveals Poulenc's craft, which is utterly charming.