Witold Lutosławski’s Chantefleurs et Chantefables is a song cycle for soprano voice and chamber orchestra, completed in 1991. Textually, the songs use the poetry of twentieth-century French surrealist Robert Desnos (1900 – 1944). A series of children’s poems, compiled and published posthumously in 1955, under the title Chantefables et Chantefleurs (Lutosławski reverses the title to distinguish the poem’s publication and his musical composition), Lutosławski takes nine poems for his cycle:

- La Belle-de-nuit (The Marvel of Peru)

- La Sauterelle (The Grasshopper)

- La Véronique (The Speedwell)

- L’Eglantine, l’aubépine et la glycine (The Dog Rose, the Hawthorn, and the Wisteria)

- La Tortue (The Tortoise)

- La Rose (The Rose)

- L’Alligator (The Alligator)

- L’Angellique (The Angelica)

- Le Papillon (The Butterfly)

Today, I want to focus on the 9th song of the cycle, “Le Papillon” (The Butterfly), as I think it presents a compact opportunity to look at numerous aspects of Lutosławski’s compositional technique. For example, it demonstrates the musical kernels and composition techniques that he uses to build movements and works from. Looking at “Le Papillon” will also provide a snapshot into his harmonic thinking and the use of ad libitum techniques often called limited aleatory or aleatory counterpoint.

The score to the entire song cycle can be found on issuu, click here to see it. I also found a thesis that includes an analysis of Lutosławski’s “Chantefleurs et Chantefables”, this helped me with some broader observations and I would recommend it, if you would like to learn more about the song-cycle.

General points regarding Instrumentation and reading a Lutosławski score

Covering some essentials, the instrumentation of the entire song-cycle is what we might call a chamber orchestra and includes, soprano voice, 1 flute, 1 oboe, 1 clarinet (doubling piccolo and bass clarinet), 1 bassoon (doubling contrabassoon), 1 trumpet, 1 french horn, 1 trombone, percussion (vibraphone, xilorimba, xylophone, tubular bells, glockenspiel, side drum and tambourine), timpani, harp, piano (doubling celeste) and strings (minimum: 8.6.4.4.2). However, in “Le papillon”, the trombone is omitted and the percussionist uses, only, a tambourine and the xilorimba.

When reading a Lutoławski score, I would also recommend reading the instructions provided at the beginning. While I plan to go into Lutosławski’s instructions for ad libitum sections later, it is worth baring in mind how his scores use accidentals. The standard is for accidentals to carry through a bar. However, in Lutosławski scores they only correspond to the note they precede. Moreover, headless notes imply a repetition of the preceding note.

Structure, Text and melody

Unsurprisingly, the structure of the composition is around the song’s text, with Lutosławski using several strategies to give the short composition shape and a sense of drama. For example, we can break the poem into four units, two of which share a thematic similarity:

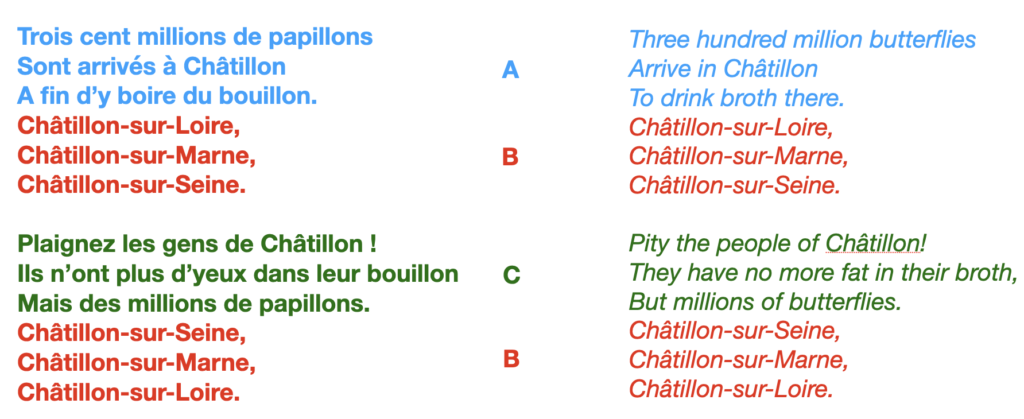

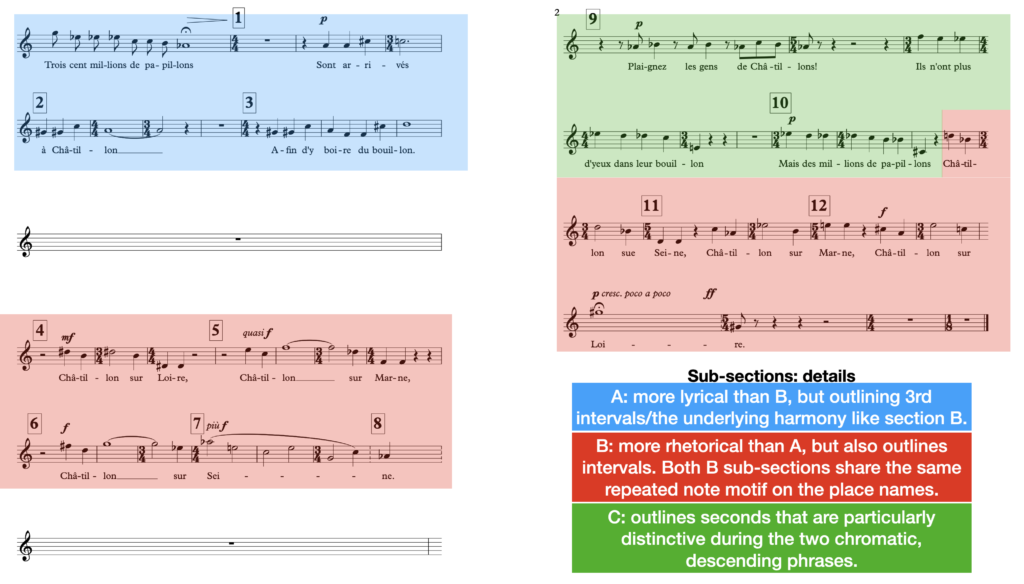

As we can see from the example above, each stanza has six lines, and each stanza comprises two halves of three lines, following an A, B, C, B structure.

Lutosławski marries the music with this poetic structure, giving each sub-section consistent thematic material. In other words, while each idea feels like a part of the whole composition, each section contains melodic qualities that are similar to other phrases within their wider sub-section. Sub-section C, for example, is the most distinct and is characterised by its use of stepwise motion. At first, a major-second motif, the second and third phrases present falling, chromatic, ideas.

Sub-sections A and B, in comparison to C, both make use of third intervals (diminished 4th enharmonic, sometimes) that often relate to the underlying harmonic progression. Instead, these two sub-sections differentiate themselves gesturally. Sub-section A capitalises on its slightly longer lines to produce more substantial, lyrical phrases of cantabile quality; sub-section B becomes more punctuated, rhetorical and motivic. In other words, A is more songlike and flowing in melody and text, and B is a series of short statements that the sub-section’s melodic material actively articulates via the repetition of notes on each syllable of the place names.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up for our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

In early 1778, Mozart was touring from his home in Salzburg to Paris. Stopping in Munich and Mannheim first, Mozart composed many sonatas on this journey. A collection of these includes seven Violin Sonatas (No. 17 - 23). The E-Minor Violin Sonata, No. 21/K. 304, is the only minor key sonata in this collection. I decided to take a look at this sonata, in part for that reason, but also because I found the clarity of its composition compelling. Using texture to clearly state themes and then present interesting variants, I think it's a good demonstration in what I think can be easily forgotten as a composer or arranger: less can be more. Below I explore the works contextual origins, before analysing the first movement in more detail, focussing on its composition.

Text, textures and musical climax

In addition to characterising each part of the text through melody, Lutosławski also punctuates the form of this movement, giving it a dramatic arc through the use of ad libitum techniques. As I said, in passing, “Le papillon” is significant in the song cycle, not only for being the last movement but for being the only movement where Lutosławski uses his ad libitum (or limited aleatory) technique. The use of ad libitum passages distinguishes the movement by creating distinctive textures, which bring a sense of climax to the song cycle. However, it also articulates the structure of the movement itself. For instance, Lutosławski uses the technique three times in this movement: once in the beginning, once between the stanzas and once close to the end. The simple use of this technique, which stands out on the page and in performance, bookend the stanzas and movement.

In combination with the changes of melodic quality, these textural punctuation marks draw out general changes of mood between the sections of the piece. In the first stanza, there is a sense of trepidation, followed by a rise in tension. This rise in tension is achieved by the rising phrases of sub-section B, climaxing on a high Ab. In the second stanza, the falling chromatic phrases communicate a sense of lament, dejection or “pity”. The three million butterflies, doubtless a sight to behold, become a pest or plague, stealing the people’s broth. The ad libitum textures serve not only to imagine the chaos of the butterflies in flight but to allow the text to breathe and for the listener to feel the shifts in feeling.

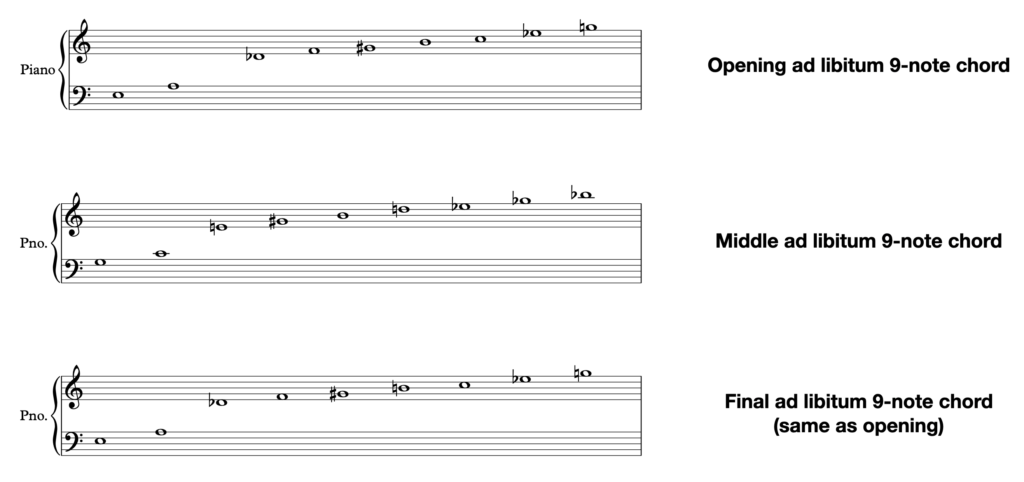

In addition to bookending the movement and stanzas, Lutosławski uses the structural significance of these textures to his advantage by imposing a larger harmonic arc. Using the same 9-note chord voicing, Lutoslawski merely transposes the chord up a minor-3rd in the middles section so that the chord starts on a G instead of an E. The final use of the ad libitum technique sees the same chord voicing and pitches used in the opening. It is worth bearing in mind that Lutosławski while using similar motivic and gestural qualities between these aleatory textures, does not simply copy and transpose the same material. He does vary them musically too.

Ad libitum/Limited Aleatory/Aleatory Counterpoint Technique

Before moving onto harmony, it is worth briefly discussing Lutosławski’s ad libitum technique, as I think this piece provides a handy snapshot into the practice and how Lutosławski instructs these passages to be performed on the page.

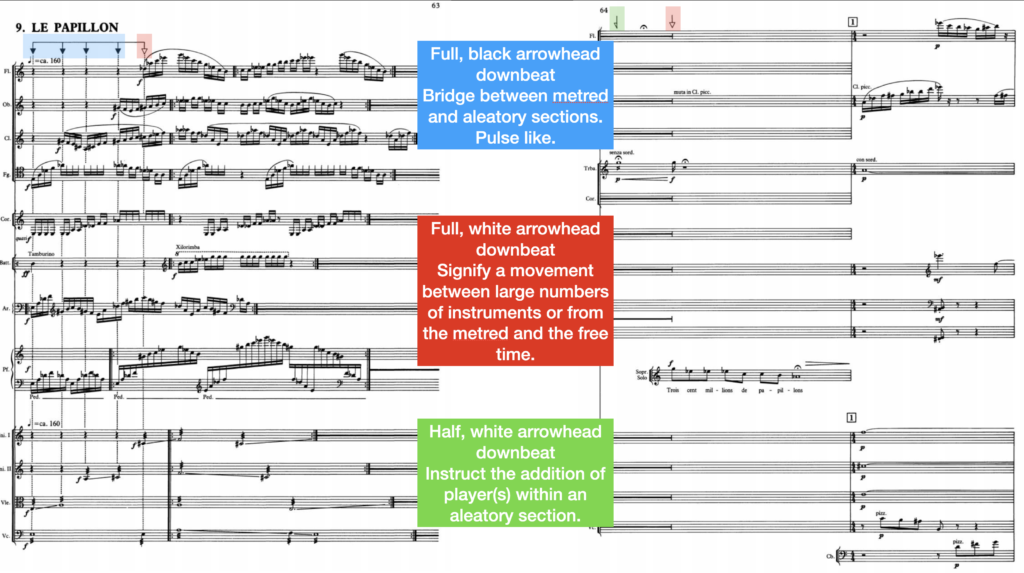

Taking the opening of “Le papillon”, we can see that it opens with a flurry of activity that cascades upwards through most of the orchestra. In this opening, the music is a kind of bridge between the metred and the aleatory. Lutoslawski uses dark arrowheads and dashed vertical lines to inform the players to play in time with one another, lining up with each downbeat.

Effectively five pulses, where the players play in time, the music suddenly shifts to a free time texture. This change is denoted by the white arrowheaded downbeat that tells the conductor and players that this is the point at which vertical alignment no longer matters. Each player, therefore, is free to play their respective repeated phrase until instructed otherwise.

Lutosławski is careful to construct repeated passages that start at different points and which boast different lengths. Therefore, while players might maintain a tempo set out by the opening pulse, their parts will slide out of synch with one another, inviting different combinations and counterpointing of notes.

Within these aleatory passages, Lutosławski has the conductor use a more subtle left-hand cue to add further players to the texture. To differentiate this instruction in the score, Lutosławski uses half an arrowhead. We can see this through the introduction of the trumpet at the top of page 64. Lutosławski uses the left-hand gesture for its clear difference to the standard, right-handed, downbeat seen in the opening.

In essence, the right hand instructs a progression for all instruments, while the left hand applies to sub-sections or individuals. The progression instructed by right-hand downbeats could be the addition of players, as it is in the very opening, or a transition or subtraction, as it is toward the end of this opening section. Lutosławski uses a white arrowhead to instruct the ensemble to suddenly cease playing and for the voice to enter, creating a dramatic shift in the piece’s texture before moving to a standard metred passage.

Harmony

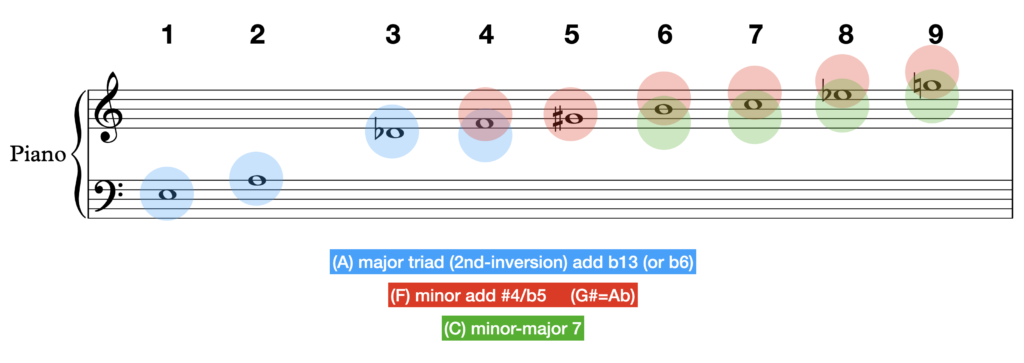

Lutosławski is known for using 12-note chords in many of his pieces. However, in “le papillon”, while using many pitches through the metred sections, he derives much of his harmonic language from the opening aleatory 9-note chord texture. For example, if we extract the sustained chords between rehearsal marks 1 and 6, we can see Lutosławski uses only three chord types:

- an augmented chord quality, with the major triad and added flattened-13th (or 6th);

- a minor-major7th chord;

- a minor triad with added #4 (or #11);

Each of these chords can be linked to the opening 9-note chord.

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves

The most significant of these chords, which is easiest to spot and extract, is the major triad with flattened 13th. This is because it appears in the same voicing, in both the extract we are looking at and the 9-note chord reduction. Both are voiced to outline the augmented quality, presenting a major triad, in second inversion, with the added b13 just above the 3rd (hence my decision to call it a b6 before).

The other two chords are slightly less obvious as they are voiced slightly differently in their block chord forms. For instance, in the 9-note chord, the 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th notes form (enharmonically) a minor chord with added #4. However, when voiced in a block chord within the piece, Lutosławski presents each of them as minor triads over the top of a #4. Similarly, while the minor-major7th chord is presented in a broken 3rd-inversion form in the 9-note chord, in the extract, it is in a stacked root position.

Harmonic Progression: Cycle, Sequence and Voice-leading

Why and how Lutosławski chose these sub-chords or the 9-note super-chord is not something that I can answer. However, it all feels very deliberate: something that Lutosławski would do, based on what I know about his composition technique. Furthermore, many of the choices feel aesthetically appropriate. For example, the use of the added-b13 (or b6) as an augmented sonority suits the surreal aesthetic of this poem. Desnos was a surrealist poet, and this is a surreal poem where millions of butterflies steal people’s broths. The augmented triad is something of a surrealist trope, used in many pieces to evoke the magical, surreal or dreamlike.

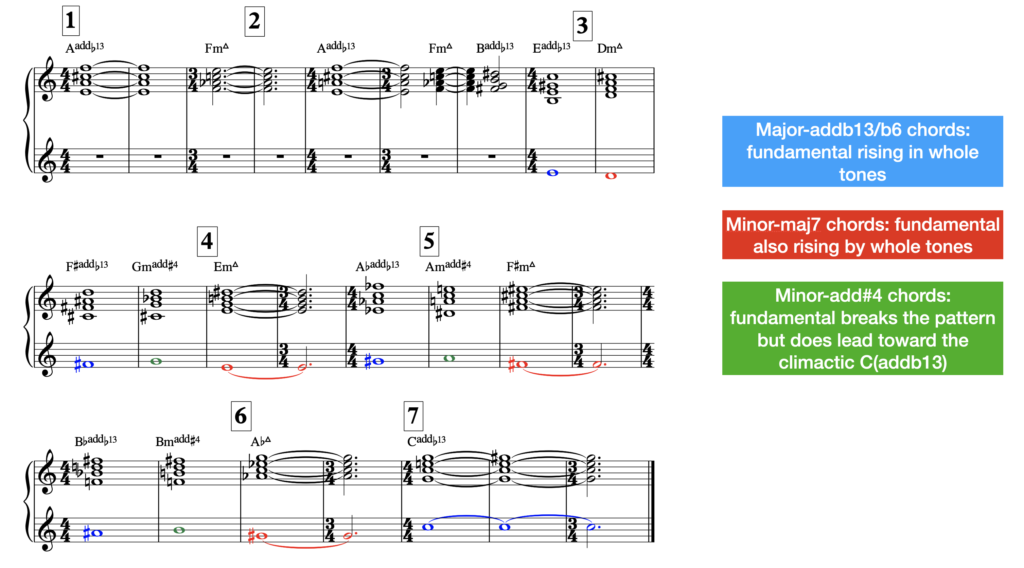

Lutosławski’s harmony through this section follows several patterns that shed light on his thinking. If we start from rehearsal mark-3, an intervallic sequence unfolds, along with a cycling of the different chord structures we have discussed. For example, each three-chord phrase follows the pattern of add-b13 (or b6) chord, add-#4 chord and minor-major7th. At least, up until the Ab-major7th structure at rehearsal mark 6. Moreover, if we follow the root of each chord, we can see it follows a pattern of (D) up a major-3rd, (F#) up a minor-2nd, and (F) down a minor-3rd to restart the cycle (E).

In addition to the sequential progression of the harmony that we discussed previously, Lutosławski also uses a sequence to control the lowest voice’s progression in the chordal padding of his accompaniment. Different intervallically, to the fundamental progression, the lowest voice follows a pattern of up a minor 3rd, followed by down a minor-2nd. Repeating the note that it falls onto once, to end the sequence, the pattern starts again, climbing a minor-3rd. Upon closer inspection, it is remarkable just how many patterns emerge in this passage.

Another fascinating progression that these combinations of chord structures facilitate is a rising minor-2nd, or chromatic, voice-leading in the upper three voices. As we mentioned earlier in this article, this section of the music is rising in tension, building to a climax with the soprano voice part. Lutosławski’s use of rising semitones accentuates this rise in tension harmonically. However, rather than simply having all voices rising in semitones, there is a sophisticated progression that adds nuance. The bass and root progressions all have descending parts but ultimately rise with each beginning of the larger phrase structure. By doing this, Lutosławski can keep the tension rising for a longer duration, making the musical climax all the more dramatic and poignant once we reach it at rehearsal mark 6.

*Thanks to Redditor dakleik, in r/musictheory, for their observations regarding the chromatic voice-leading and the bass progression. I was initially caught up by the sequential whole-tone rising pattern, but these other structures seem much more deliberate and what Lutosławski may well have been purposefully thinking about while composing this movement.

Close

An utterly charming song-cycle, we can also see how, below the charm, there is a great deal of sophistication as well. In analysis, in deconstruction, Lutosławski demonstrates how a composer can connect different structures to create engaging and fitting progressions. From a composition perspective, in construction, however, Lutosławski shows us how there is more to be had from those structures and ideas we already have.

- If we have one structure, could we invert or retrograde it to create a form of symmetry?

- If we have a chord or pitch set, could it be used as the basis of a progression or sequence?

So often in composition, we think we need to keep building and finding new answers. Lutosławski shows us that the answers might already lie in what we have.

Beyond these structural interconnections, Lutosławski also opens the door to different textures and sonorities. He shows us, via his limited aleatory technique/aleatory counterpoint, how we might control time and instrumentalists in different ways to create compelling sounds. Most importantly, he lets us hear what 3-million butterflies, in flight, sound like.

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …