Master the Art of Horrifying Orchestration

Join us and develop the skills to scare your listeners.

Use coupon code scar3yd15count for £50 off!

It may be a surprise to readers that Debussy is not a composer whom I have studied very much in University or since. Come to think of it, I cannot recall much being taught about Debussy in University lectures either, which again may be a surprise. (Incidentally, I do recall my Modern Music Lecturer opening their Modern Music course with a recording of Prélude à l’apres-midi d’un faune.) However, recently a composition student of mine became interested in Debussy’s Arabesques, particularly the first, and wanted to compose something of a similar ilk. This student’s interest, therefore, seemed like a wonderful excuse to acquaint myself with Debussy and specifically his Arabesque No. 1 a little better.

In this article, therefore, I present a thorough analysis of Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1 (composed in 1888), investigating the structural arrangement of the composition, the structure and form of its several melodies, and Debussy’s use of harmony.

If you’d like to be updated when we release new article and videos, sign up for the Any Old Music Mailing List.

Credit/References

There are a couple of YouTube videos that I used to help inform my analysis, particularly with the harmonic language that Debussy uses in his Arabesque. Without them I may not have been able to make the observations regarding harmony and other aspects that I make, as they saved a lot of time in labelling the chords etc.

The first of these videos is Timon de Nood’s Debussy’s first Arabesque – Analysis. The second is Bruno Robles-Rendon’s Debussy no. 1 Score Analysis (Harmonic and Structural).

Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1 (Score Video)

What’s an Arabesque?

I am always primarily concerned with the music composition: the notes that Debussy writes, what they mean and what they can teach us about music composition and arrangement. However, it is worth discussing what “arabesque” is for a moment, as its conceptual influence on Debussy, for the first arabesque, is striking.

We would be wrong to assume that the title Arabesque No. 1 implies an exploration of Arab, Middle-eastern, Asian or Eurasian music. What I mean by this is Debussy is not exploring the harmony or melody writing of those geographical and cultural locations. For example, if we take Saint-Saens Barcarolle or “Turkish” influences in operas, symphonies and sonatas of the classical period. These, however well you might think they do it––or not––explore or try to recreate qualities they have identified in the music of a culture. Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1 is not an attempt to do this.

Instead, Debussy is exploring arabesque as it appears in art, music––possibly Ballet, in which Arabesques are various postures––and certainly architectural style, taking it as the inspiration for composition. This art style is prevalent in Islamic cultures, being used decoratively on and in mosques, palaces and on vessels and jewellery. However, it also appears in European art during the Roman and then the Renaissance period. (It sometimes reminds me of the circular, snake motifs one finds in Celtic art.)

As a style, the online Britannica encyclopaedia describes Arabesque as a “style of decoration characterised by intertwining plants and abstract curvilinear motifs.” And, the Renaissance Arabesques as “[maintaining] the classical tradition of median symmetry, freedom in detail, and heterogeneity of ornament.” In other words, the art balances elements of strict control, such as in the repetitive-sequential and sometimes recursive designs of motifs, with spontaneous, curving, waving and flowing shapes that take the form of flora.

It is the combination of the organic and human endeavour to artistically create the organic that could be said to be inspiring Debussy in the Arabesque. With line, symmetry, pattern and motif; artistic tools toil with the beauty and wonder of nature. If we take, for example, bar 63 – 65 of Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1, where he abruptly modulates to C-major, one can observe a symmetrical pattern in melody and bass contour and the underlying harmonic progression. The melody descends and then ascends in a shallow V-shape, while the Bass does the inverse. Similarly, the harmonic progression proceeds I-IV-V-vi, resting on V, before reversing the progression: vi-V-IV-I. The passage is not symmetrical in every detail, but boasts symmetrical qualities. (It is symmetrical enough for me to say its symmetrical, and––I would hope––for you to agree!) Like nature, one can see patterns––or one can certainly feel they see patterns––but those patterns are rarely perfect. Nature is beautiful for its mixture of symmetry and asymmetry, pattern and randomness.

Master the Art of Horrifying Orchestration

Join us and develop the skills to scare your listeners.

Use coupon code scar3yd15count for £50 off!

Structure/Arrangement

Below is a tabular analysis of Debussy’s Arabesque No. 1, which breaks the arrangement of the work down into varying units of scale. For example, the column Structure Label defines the work on its broadest scale as a ternary structure. However, we can only come to understand the work on this larger scale due to what it does with Melody and Tonality, on smaller scales.

If we look at the Melody column, for instance, we can see that a number of the melodies (1 – 4) return in the second A section of the work. The only omission in the second A section is the fourth theme that occurs at section label D. This theme is not recapitulated in the returning A section.

If we look at the Tonality column, we can see the same tonal pattern is also largely repeated between the two A-sections. Arguably an inessential feature, the return of these keys gives the work a degree of symmetry. For example, excluding the move to C-major at section label H, the tonal progression would be E – A – E – A – E – A – E.

In correlation with the Arabesque as an art form, if we reconsider the tonal progression with the C-major placed back in: E – A – E – A – C – E – A – E, I think there is a consistency between the beauty of nature and the Arabesques representation of this. Using symmetries and geometric qualities, nature boasts these same qualities along with moments of spontaneity. Or, what we might see as beautiful imperfections or blemishes. As much as we like to intertwine nature with mathematical order, nature’s forms have a propensity for occasional, beautiful chaos.

If you’d like to be updated when we release new article and videos, sign up for the Any Old Music Mailing List.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Arabesque No. 1 – Claude Debussy | |||||

2 | Section Label | Bar No. | Structure Label | Melody | Tonality | Notes/Details |

3 | A | 1 | Intro | 3 (seg.) | E (I) | Stepwise descending bass motion ending on V9. |

4 | 3 | 4 (var. & seg.) | ||||

5 | B | 6 | A | 1 | Static and then step ascending bass. | |

6 | 10 | 2 | ||||

7 | C | 17 | 3 | Full theme with a consequent that is then explored as a transition into D. Stepwise moving bass descending at first then moving both ways. | ||

8 | 23 | A (IV) | ||||

9 | D | 26 | 4 | Full theme with a consequent. | ||

10 | 29 | E (I) | ||||

11 | E | 39 | B | 5 | A (IV) | Texture becomes more homophonic in quality, with block chord voice leading. |

12 | F | 47 | 6 | Rising 4ths in the bottom note of each broken chord (right hand/treble staff) landing on B at 48. | ||

13 | G | 55 | 5 | Near replica of Section Label E, Bar 39. | ||

14 | H | 63 | 5 | C (VI) | Mirror progression at 63-65: I-IV-V-vi-[V]-vi-V-IV-I, with stepwise movement in the bass: E-F-G-A-[B]-A-G-F-E | |

15 | I | 71 | Intro | 3 (seg.) | E (I) | Replica of Intro |

16 | 73 | 4 (var. & seg.) | ||||

17 | J | 76 | A | 1 | Replica of Section Label E, Bar 6 | |

18 | 80 | 2 | ||||

19 | K | 87 | 3 (Var.) | Variation of Section Label C, Bar 17: Theme 2 antecedent the same, but varied consequent. | ||

20 | 91 | A (IV) | Exploration of theme 2 consequent transitioning to Coda. | |||

21 | L | 95 | Coda | 1 | E (I) | After a brief V pedal the harmony rests on I, reiterating the theme 1 antecedent, before breaking down into a rising broken chord idea on I to end the piece. |

22 | ||||||

23 | ||||||

24 | Section Label | These correspond to the rehearsal marks I have placed on my annotated score. | ||||

25 | Structur Label | These highlight a sections structural function. | ||||

26 | ||||||

27 | seg. | Segment | Essentially a fragment of a melody, but more substantial. | |||

28 | var. | Variant | ||||

Master the Art of Horrifying Orchestration

Join us and develop the skills to scare your listeners.

Use coupon code scar3yd15count for £50 off!

Melody

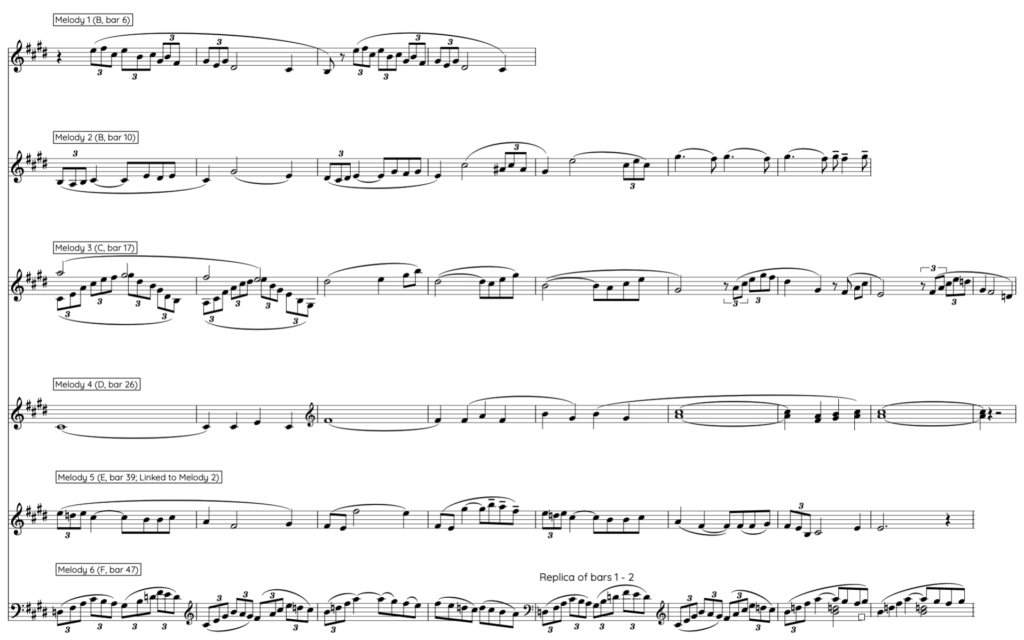

Looking at the Melody column of the tabular analysis, we can see that Debussy’s Arabesque boasts 6 different melodies. And, while the melodies never feel unconnected (in fact the opposite is true), it is worth noting that this is quite a lot of melodies for a shorter composition to have.

My opinion is that Debussy creates a piece so rich in melodic content to reflect the qualities one sees in Arabesque art. Sprawling, flowing, cascading across a wall, this composition feels like an impression not so much of an Arabesque itself but of one’s experiencing of an Arabesque (or any) art work. At one moment we may focus on a part of the work, then another part, and then we might step backward to take a wider view. Yet, we cannot do both. We can only take one perspective in a given moment and another in the next. Debussy’s changes and reprisal of melodies, to me, encapsulates that experience. One moment we focus here, then we focus here.

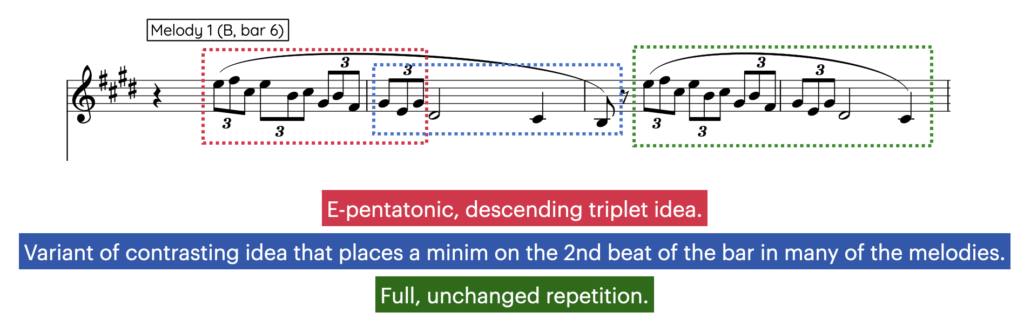

If we extract the themes of Debussy’s Arabesque we can immediately begin to see, at once, the remarkable vitality and consistency of the melodies. For example, there is a clear emphasis on the second beat, in many of the melodies. Melody 3 being the only exception; Melody 1, is the clearest as it explicitly starts on beat 2, with beat 1 boasting a rest. The other melodies emphasise beat 2 by placing longer and stronger valued notes on the second beat:

- Melody 2, in its opening 5 bars places the longest note on each of its 2nd beats. These notes tend to be the duration of a dotted crotchet, engraved as a crotchet tied to a quaver––due to its positioning in the bar––or a minim.

- Melody 5, which we will compare to Melody 2 shortly, also emphasises beat 2, as does…

- Melody 6 after its triplet figures in bar 1 – 2 and 5 – 6.

Melody 4 takes on a slightly different approach to emphasising beat 2. Rather than using a long note, it generally starts moving on beat 2, with beat 1 being suspended from a note in the previous bar. The result is an emphasis on the second beat, which is a consistent feature of all the melodies.

Melody 1 into 2

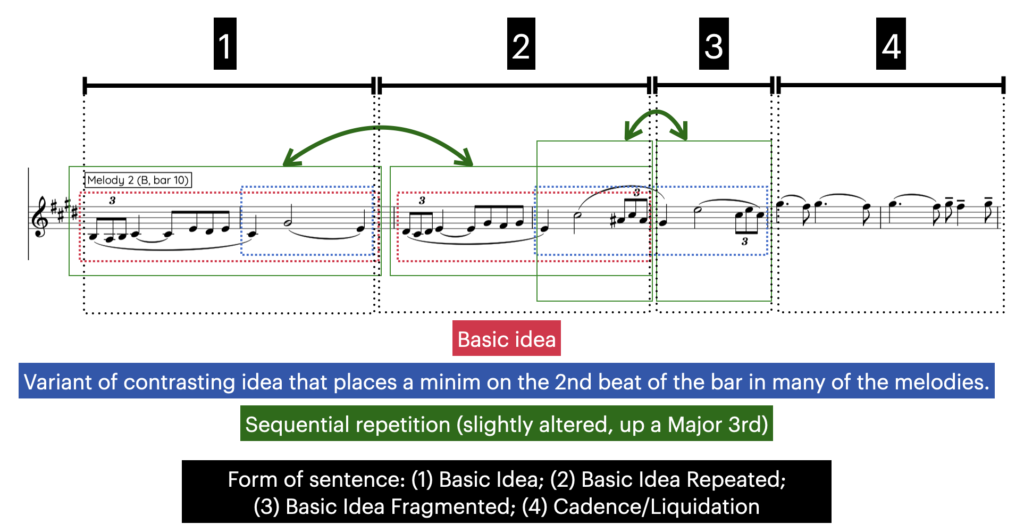

There is so much to observe in the melody writing of this composition, I am going to struggle to do it all justice. For example, in analysing the piece, I initially labelled Melody 2 as the consequent of Melody 1, before deciding it was a melody that needed distinguishing as its own thing. However, I do think there is something to be said about how Debussy creates engaging melodies: not only through what they are formally but how they occur in arrangement.

Like the growing roots of a tree, Melody 2 shoots out from Melody 1. However, it is Melody 2 that takes on a fuller existence, experiencing its own degree of development. Melody 1 is very succinct and simply occurs, whereas Melody 2 presents a basic idea, transposes and then fragments itself in something of a sentence form. Only the consequent section’s development of the basic idea is more of essence as opposed to something clear and specific. In other words, the motif of melody 2, in bars 4 and 5, feels natural but does not have the clear link to the basic ideas of the antecedent. Unlike the explicit fragmentation one can witness in many of Beethoven’s sentence forms.

Neither right nor wrong (there is no right or wrong), it is simply another way of doing things.

Melodic development in Melody 3

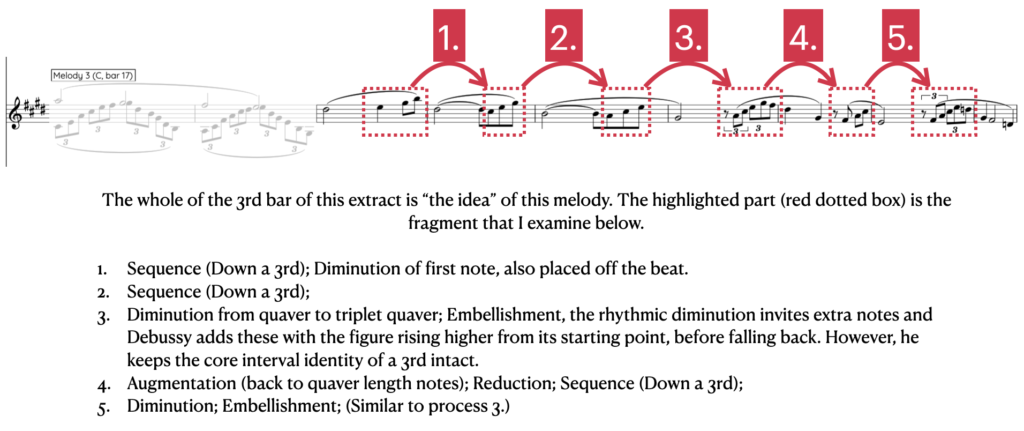

The third melody is one of my favourites, due to its design. To me it feels quasi-improvisatory. What I mean by this is that, its clearly crafted but the manner in which it unfolds feels like a performers musings. For example, after the phrase that opens the piece, we have what could be described as a consequent phrase. However, this consequent phrase presents its own idea that is developed through a process of fragmentation, sequence, diminution/augmentation, embellishment/reduction.

Highlighted in the figure below, the melodic idea of the consequent section of the melody is transposed downward, as part of a melodic sequence, several times. This is done by a 3rd diatonically, with the notes keeping to the key signature of the section. Debussy also uses diminution and augmentation, particularly near the end of the consequent, which invites processes of embellishments and reductions. Switching from quaver to triplet quaver figures, then back again, this process leaves space for a few more decorative pitches, that Debussy gracefully fills in.

As always, I don’t think Debussy will have thought so clunkily in composition, as we are in analysis. It could well have been an intuitive moment of improvisation. However, I think even in that intuition there will be these processes occurring rapidly and impromptly. Constrained to the melodic idea he gives himself in bar 3 of the figure, sequential improvisations and small-scale embellishments will not be something Debussy could not do on the fly and then write and, possibly, revise––if he sees fit.

The important lesson to take from this melody is its structure and what can be done with a simple idea, with straightforward techniques of composition such as fragmentation, sequence, embellishment (or reduction) and altering note lengths (diminution/augmentation).

The Period Melody [No. 5]

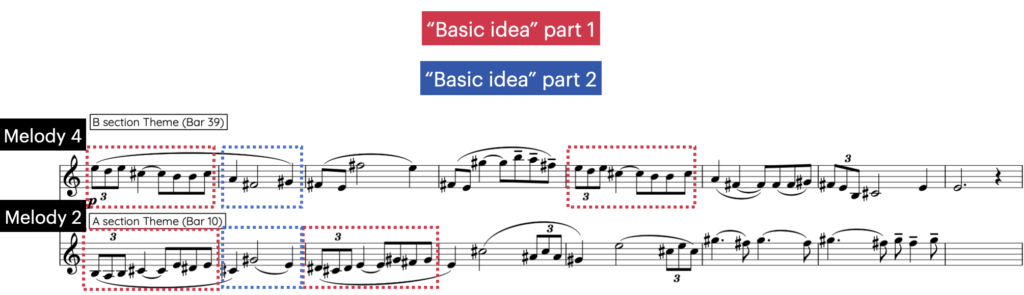

The last of the 6 melodies that I want to look at, the basic idea of this melody is strikingly similar to Melody 2. Using the same rhythm, one largely ascends while the other descends. Not every interval direction is inverted, but it is very close.

Another striking feature of these melodies, however, is their different structures. As mentioned when looking at Melody 2, it was in a form of sentence, where the basic idea is stated in succession during the antecedent. The consequent is then, typically, an exploration of that basic idea. The period form, however, is where the antecedent and consequent sections of the melody both start with the basic idea. The other halves of the antecedent and consequent usually present complementary, cadential material. In this regard, Melody 4 is a clearer period form melody than Melody 2 is a sentence form melody, based on the stricter classical models of these two forms.

Master the Art of Horrifying Orchestration

Join us and develop the skills to scare your listeners.

Use coupon code scar3yd15count for £50 off!

Harmony

Functional enough.

Starting first with a summation, Debussy’s harmony in Arabesque No. 1 is not always functional, but not always not-functional either (LOL.). Functional harmony relies on a clear polarity between dominant (V) and tonic (I), which tells us explicitly that the key is x, y or z. This relationship can often be made clearer by root motion of a fifth too. In other words, both the dominant and tonic chord are in root position within the progression. In essence, the dominant and tonic function together to inform us of the tonality of a phrase, section or composition.

Debussy’s Arabesque makes frequent use of dominants and tonics and its not too difficult to apply Roman numeral analysis to the chords he uses (thank you, again, to Timon de Nood’s and Bruno Robles-Rendon’s respective videos). On a larger scale, for example, Debussy oscillates between E and A-major, which are adjacent to one another on the circle of fifths, outlining a dominant relationship. A is the subdominant of E; E is the dominant of A. However, in the smaller scale harmonic progressions, Debussy infrequently gives us dominant and tonic chords in succession. Moreover, he regularly uses progressions and stepwise progressions that are often tonally clear, but not functional in the way that we have described.

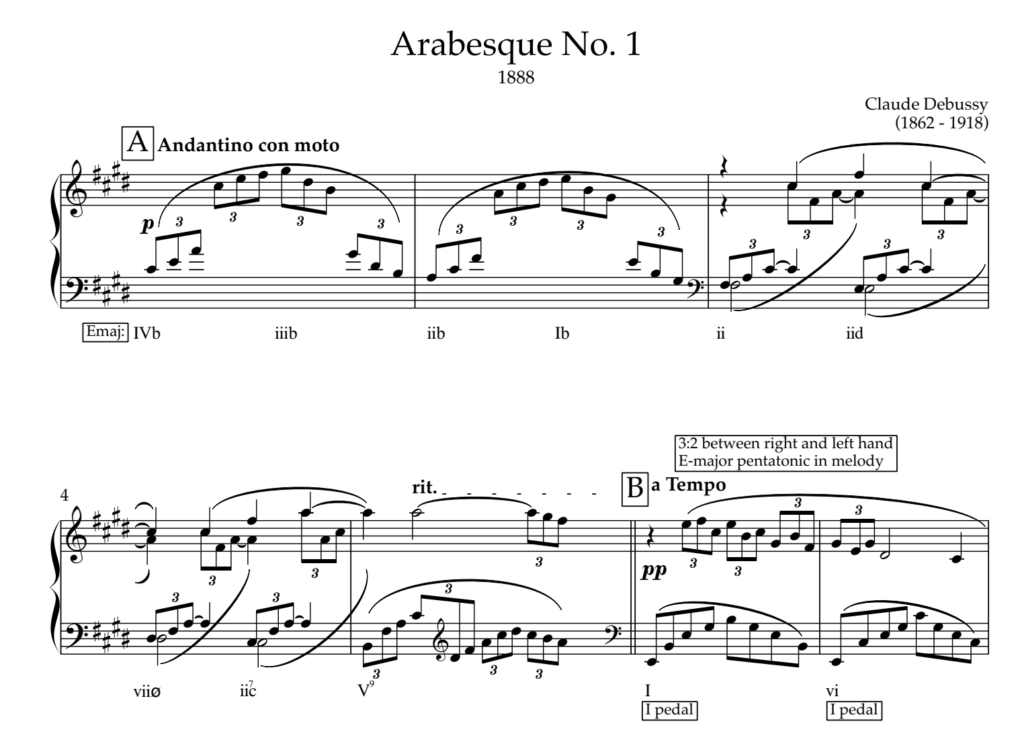

For example, there is a fantastic progression that opens the piece. It is diatonic, and has some strong uses of chord I and V. However, chords I and V are never in succession. Across the five bars there is a stepwise descending bass line that starts on chord IV and ends on chord V. Moreover, the end of the first two bar phrase settles on chord I. None of the chords are chromatic, and the use of chord iii, the mediant, rather than chord V gives us the pitch information of E-major. It is not declamatory, like a V to I progression, but suggestive and fluid. The tonality and modality take time to unfold and are not given to us, the listeners, immediately.

Stepwise Basslines and the use of V and V/Vs

A point to highlight from the above example, which I will return to shortly in more depth, is Debussy’s extensive use of inversions. Debussy typically uses these to facilitate his often stepwise moving bass lines. The opening two bars demonstrate this most clearly, by presenting a succession of descending broken first-inversion chords. These set up the descending bass line that Debussy persists with through to bar 5.

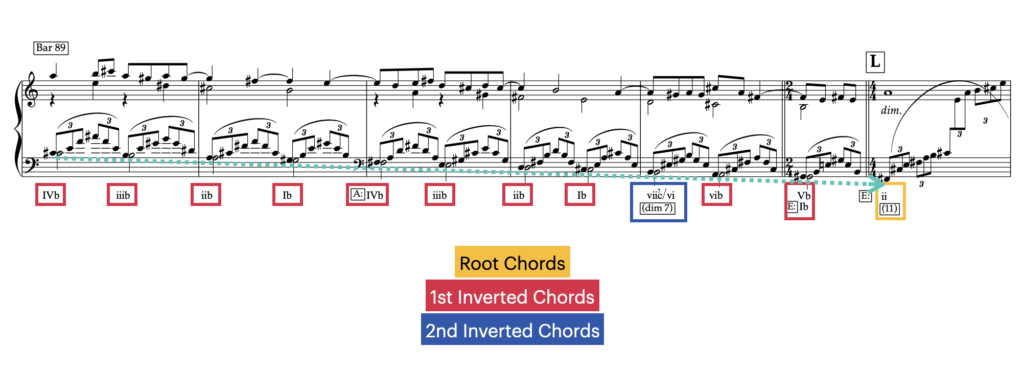

Another example of a stepwise, indirect but clear progression occurs close to the end, at bar 89. Here, Debussy goes on a huge stepwise descending adventure, presenting a chord progression that weaves us between the core tonalities of this composition: E and A. We do not have E-major or A-major proclaimed perfectly with a V to I, but through the use of scale patterns and pitch content. The progression is more indirect, with the tonality emerging gradually rather than immediately. While we embrace the beauty of each chord and note as they happen, we have to step back to see the whole. It is also worth noting the near exclusive use of 1st inversion chords through this passage too.

Returning momentarily to the opening of the composition, Debussy does move from chord V to chord I between the two sections. And, one can find other examples of perfect cadences. However, one simple harmonic device that I do find beautiful about this piece is that Debussy often builds the expectation for a tonic chord by sitting on chord V or a V/V for a moment. And, usually, he does this at a structurally significant moment. Moreover, sometimes he satiates our want for the resolution, but at others he does not.

Like the curving motifs of an Arabesque he will introduce the new tonality, prepared by a V, by introducing another important chord of the progression. For example, in bar 37, Debussy gives us a V of IV. Or, in the key of E-major, the tonic chord that will be revealed as a pivot into the subdominant, A-major. However, at 38, when the A-major section begins, A-major is not the chord we get. Instead, Debussy starts the progression on the super-tonic. He then proceeds with this progression, not giving us our new tonic chord until bar 42.

You may be sat there thinking so what? However, I think it can be so easy as composers––especially at a structurally significant moment, where we may have used a V chord––to move directly to the tonic chord of the new key we are entering. I know it is a tactic I have frequently used when deploying dominant pedals and preparations as a means of building expectation for a recapitulation or something like that. Maybe in the future I should not be quite so direct!

Contrasting Inversion and Root Position Progressions

Another interesting tactic, increasing the vitality of Debussy’s harmony, is his use and non-use of inversions. For example, if we take the figures that we have just explored, the two stepwise bass progressions use many, many inversions. Meanwhile, the last example demonstrates a chord progression that uses root position chords. The effect of this is sections that contrast on multiple levels, one of those levels being the bass progression and the clarity of the harmony.

Root position triads and progressions made up of root positions are crystal clear. Inversions change the clarity of progressions, but add colour grades and shades to the contrasting root position chords. Debussy for me presents floaty, dreamlike stepwise progressions, which contrast with more declamatory or proclamatory root position progressions. When we think of harmonic contrasts, we might think of tonality or mode and maybe harmonic structures such as extension or voicing such as tertiary or quartile. It is easy to forget about bass progression and inversion as a device for further enriching our harmony across an arrangement. Debussy shows us the way in Arabesque No. 1.

Master the Art of Horrifying Orchestration

Join us and develop the skills to scare your listeners.

Use coupon code scar3yd15count for £50 off!

Close

As I did not want to labour the point, there are many opportunities where one can see a connection between visual qualities in Arabesques and musical qualities in Debussy’s Arabesque. In fact, it could be one of the best compositions that takes a non-musical stimulus, such as a piece of art, that I have ever had the pleasure of analysing. The reason I say this is that Debussy takes the Arabesque inspiration, or certainly plants it into our mind, and turns it imperfectly into music. What I mean by this is, he takes broader techniques of symmetry, sequence and motif, but does not try to force the music into strict patterns of symmetry, sequence and motif. He gives himself space to compose the music, while also presenting clear lines and contours that present parallels to his inspiration. Balancing the rational and irrational, Debussy presents us with a beautiful Arabesque.

If you’d like to be updated when we release new article and videos, sign up for the Any Old Music Mailing List.