I have not watched many of The Twilight Zone episodes. Not for lack of wanting to, but simply a lack of paired reason and opportunity. What better way, then, to introduce myself to these highly regarded television classics than by doing so through a composer whom I hugely admire, Bernard Herrmann.

In this article, I want to look at Herrmann’s score for the 5th episode of season 1, “Walking Distance”, which aired on the 30th October 1959. The production of the score occurred a few months prior, on the 15th August. I will, generally, be keeping comments and analysis away from the perception of the music’s relationship to the picture and narrative. I do this purely to keep the points concise. Instead, the focus will be on extracting and discussing a handful of musical devices about orchestration and composition.

(I owe the possibility of producing such an article to this YouTube channel: Film Score Rundowns. It is the only place I have been able to access these scores. The uploader also offers written analyses of their own, linked in the relevant video descriptions.)

The beauty of these shorter scores, for an episode rather than a film, is that it is easier to dive deeply into them. Some of the cues are incredibly short, whereas some take on miniature forms of music in their own right. They are a treasure trove of techniques that I would recommend studying. As a result, I decided to separate the analysis of this piece into two parts. In this article, the first part, I will focus on Instrumentation and Orchestration. In the second part I will be looking at some of the composition techniques that Herrmann uses.

The article is split into three parts:

- Instrumentation and how significant Herrmann found selecting his ensembles for a project.

- Instrumental Instructions: Herrmann’s extensive use of various techniques to increase the colour of his ensemble.

- Reorchestration as a means of extending and varying material efficiently.

1. Instrumentation

It would be easy to skip over the instrumentation of the score for this episode, stating that it is simply a string orchestra. However, this misses the delicate consideration Herrmann makes in selecting the number of strings he needs and how he uses them. On a surface level, it looks like a string orchestra or string ensemble. However, Herrmann is precise with his numbering: 6.4.3.3.2. (6 – 1st Violins; 4 – 2nd Violins; 3 – Violas; 3 – Celli; 2 – Double Basses)

It is a modest ensemble of strings, possibly constrained for budgetary reasons. However, even so, why this particular ensemble? It is larger (if not in sections, but in terms of numbers of musicians) than other ensembles that he put together for other episodes of The Twilight Zone (see table below).

Series: episode: year | Episode Name | Instrumentation | Total No. of instrumentalists |

1:5:1959 | Walking Distance | 10 Violins; 3 Violas; 3 Celli; 2 Double Basses; 1 Harp* | 19 |

1:7:1959 | The Lonely | 3 Trumpets; 3 Trombones; 2 Harps; Hammond Organ; 2 Percussionists (Glockenspiel and Vibraphone) | 11 |

3:26:1962 | Little Girl Lost | 4 Flutes (w/certain parts doubling Piccolo, Alto and Bass); 4 Harps; Viola d’Amore; Percussion (Tam-Tam: large and small, Tambourine and Vibraphone) | 10 |

5:6:1963 | Living Doll | 2 Harps; Celeste; Bass Clarinet | 4 |

Table 1: Selective instrumentation and number of instrumentalists in four of Bernard Herrmann’s The Twighlight Zone episodes.

*Cheers to redditor willcwhite for pointing out that I had missed the harp. If you ever spot an error or have a query about something in one of my articles or videos, please get in touch. I try to always be as accurate as I can, but I am not without fault. 🙂

Instrumentation as Herrmann Aesthetics

The care and oddity of Herrmann’s ensembles communicate an underlying value that Herrmann places on instrumentation. While they undoubtedly allow experimentation and creative constraint, which have value to the process of composition, Herrmann’s specificity imbues each episode with a musical fingerprint. Doing this with anything else (melody/harmony), particularly in the short anthology-episodic format, would be much more challenging (if not impossible). We hear instrumentation immediately, whereas establishing harmonic and melodic elements takes more time.

In a sense, Herrmann creates an episodic individuality with great ease via instrumentation. The melodic and harmonic character can then take care of itself on much more musical and narrative terms. What I mean by this is, due to the distinctive instrumentation, Herrmann only needs to think about melody and harmony as they relate to wider conventions expected by the viewer of The Twilight Zone. Furthermore, the less standard combinations of timbres add to those conventions of the unexpected, supernatural and suspenseful.* They also impose idiosyncrasies and numeric limitations that will undoubtedly affect harmony and melody, further exacerbating their individuality.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

*In a similar genre: sci-fi, Herrmann also uses an interesting combination in The Day the Earth Stood Still: 2 Theremin, 2 Hammond Organs, Studio Organ, 2 Pianos. 2 Harps, 3 Trumpets, 3 Trombones, 2 Tubas, Contrabass Tuba, 2 Vibraphones, 2 Glockenspiel, Tam Tam, Electrically Amplified Violin, E.A. Cello and E.A. Double-Bass.

In this article I look at Ralph Vaughan-Williams' 5 Variants on Dives and Lazarus. A study in blending string timbres, I discuss Vaughan-Williams' use of divisi and blending of solo, section and specific-string timbres.

2. Orchestration Techniques: Instrumental Instructions

Herrmann uses a huge number of orchestration techniques and devices in this score, exploring string writing technique. Only a year before Psycho (1960), perhaps this piece became something of an artistic study for that score. Here I have pulled out a range of techniques that I will touch upon briefly before focussing on a couple of things more deeply: (1) a voice that I found weirdly captivating and eerie and (2) use of reorchestration to, economically, develop his music.

Con Sordino

Much like Psycho, this score extensively uses con sordino/muted strings. Herrmann uses the technique in two ways: (1) to make soft sections even softer and lighter; (2) to make loud passages sound trapped (like you’re screaming in your coffin, kind of thing. Lol. ) Adler, in The Study of Orchestration, captures the description of the latter of these beautifully. “The loud muted passage takes on a special quality of restraint and a sound that is more constricted, tenser.” (Adler, [3rd Edition] 2002:39). (A good point of contrast comes in the sixth cue: “Curtain”, where the strings are senza sordino/unmuted (timecoded link) and then immediately back to muted strings in cue seven.)

Divisi (Bowed) Tremolo and Natural-bowing

A bowed tremolo involves the oscillation of the bow back and forth. These can be measured, meaning the repetition of the notation is of a defined rhythmic value. Or they can be, as is the case in “Walking Distance”, unmeasured. The oscillations, in this instance, are performed as rapidly as possible with no consideration for a defined rhythm.

The divisi of tremolo and natural bowing is an interesting effect. Similar to how we observed them in the Dives and Lazarus article, the violins are divided, despite playing the same pitches. One part, however, is instructed to perform an unmeasured tremolo, while the other plays the line naturally. Herrmann uses the technique in the second cue (timecoded link). As you can imagine, this veils the effect of the tremolo, smoothing the line but creating a rustling effect. (As a technique, I would be curious to know how it sounded if the players were asked to play different bowing positions. For example, the natural part plays sul tasto and the tremolo part, sul ponticello.)

(The final cue uses a unison bowed tremolo, at the very end of the soundtrack linked.)

Fingered Tremolo

Simply as an opportunity to define two different forms of tremolo, Herrmann also uses a fingered tremolo in cue 5 – “The House” (timecoded link, which also shows a senza sordino passage for pizzicato double basses). This technique is similar to a trill, where the player oscillates rapidly between two pitches (rather than the bow), but spans a distance greater than the interval of a second.

Flautando

Similar to a technique called sul tasto, in that it is often just over the fingerboard, flautando instructs a quicker and lighter bow movement than natural bowing and sul tasto bow positioning. Similar to sul tasto, the tone colour is affected. Reducing the strength of the fundamental and resulting harmonics, the result is defined as flute-like. Hence the term flaut[-]ando. Herrmann briefly uses flautando at . (The video below demonstrates Molto Flautando e Molto Sul Tasto so that you can hear the techniques at their extremes.)

Natural Harmonics

Also frequently described as flute-like, in the fourth cue of Walking Distance, “The Park”, Herrmann uses natural harmonics. Slightly more resonant than artificial harmonics, as they use the open string as opposed to a stop note, the implications are that Herrmann’s harmony is bound to the (1) practicalities and (2) natural limitations of using harmonics. By this, I mean (1) the technique requires delicacy to perform and (2) the notes are limited to the harmonic series, limiting pitch content and, thus, harmonic potential. (timecoded link)

Non Vibrato

In contemporary performance practice, at least of the Western tradition that we are discussing here, vibrato is considered the default for, particularly, strings. However, in bar 14, of cue #5, “The House”, Herrmann specifies non vibrato. Typically, performed over held notes to warm the tone quality, non vibrato, creates a “pale” (Adler, 14) sound. (timecode link)

3. Economical Development: (Re-)Orchestration

Ironically, one can easily forget that a professional artist earns their livelihood through their art. To do this, much like any job, it takes time and effort to make those pennies. However, for the freelancer, the earning of those pennies is not a traditional exchange of time for money. Instead, there is an exchange of artefact for money. In other words, in this instance, music is composed and produced by the composer for a fee. Therefore, the time spent working on the music is depreciating the money earned from a fee. Furthermore, there is always an opportunity cost at play. If the composer is working on one project, that means they are unable to work on another (unless, in the rare instance a project wants them enough to wait!) and, thus, their earning potential is reduced too.

Now, this is not to say artists are only in it for the money. Quite the opposite is the truth. However, unsurprisingly, the professional composer, if they are to be sustainably professional, has to come up with crafty ways to make composing and producing effective music as efficient as they can. Herrmann, an absolute professional, has many of these tricks up his sleeve. I want to explore one crafty way here: the use of orchestration to extend and refresh a musical idea.

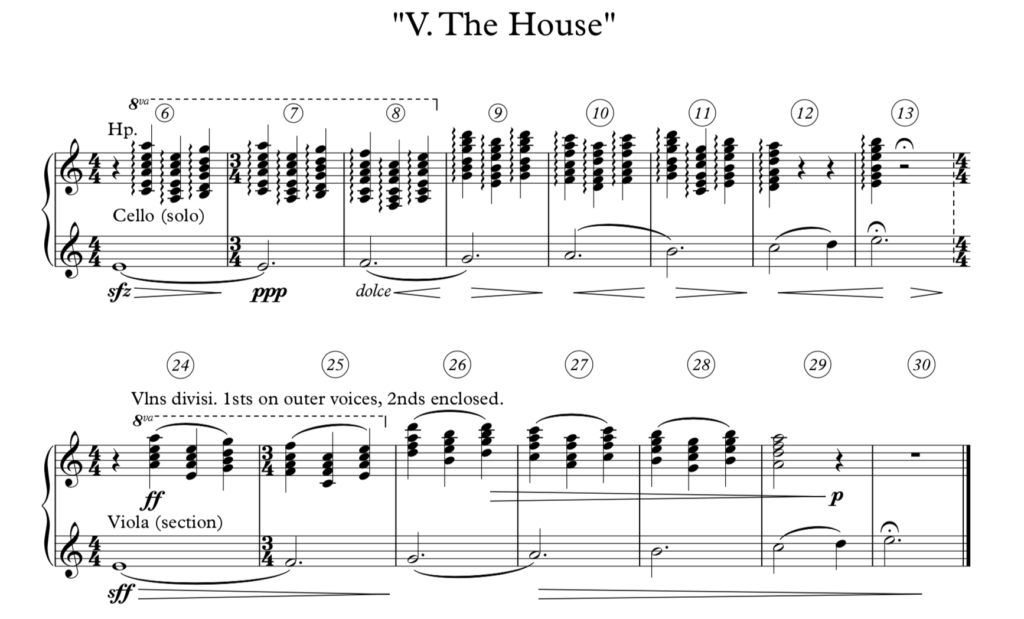

Example 1: Cue 5 “The House”

Herrmann uses orchestration, at several points, to give his musical ideas greater longevity. One notable location is in the fifth cue, “The House”. At the two points that the music switches to 3/4, Herrmann uses a similar idea. In the first instance, the orchestration is a cello solo, with a harp rolling crotchet note chords as accompaniment. However, in the second instance, which has slightly different harmonies (unless I’ve misread the handwritten score!), the melody line is given to the three violas and the accompaniment is provided by divisi violins (firsts and seconds) instead. A straightforward reorchestration, Herrmann is not only giving the cues a consistent musical idea but is also not having to reinvent the wheel either!

https://youtu.be/2Rtlqm0nSU4 If someone were to ask me what my favourite film was, I think I would be hard-pressed to answer with something

In addition to making the instrumentation changes, Herrmann also instructs different dynamic levels. Wistful, in the first instance, the cello and harp play at an amicable and delicate piano dynamic. The instruction, dolce, is asked of the cello too. In the reorchestrated passage, however, the violins and viola are instructed to perform fortissimo. They are then asked to decrescendo in the last few bars of their parts.

Looking further into the reorchestration, the voicing of the violin chords is particularly interesting. If we recall, there are six first violins and four second violins. Herrmann chooses to divisi the first violins so that they play the outer voices, enclosing the divisi second violins between them. I found this a significant change as an octave doubling and increased numbers would give this line further prominence.

These changes, the use of the violins, as opposed to harp, and the dynamic levels, create a stark contrast. In the first instance, the difference between plucked and bowed strings brings clarity of texture and instrumental roles. The cello is the melody; the harp is the accompaniment. However, there is tension in the reorchestration. Exacerbated by the increased dynamic level, homogeneity creates this tension. The parts are recontextualised as being contrapuntal, with the chordal accompaniments outer voices elevated to the status of countermelody. The two parts now fight for our attention.

Example 2: #9 “Martin’s Summer” & #10 “Elegy”

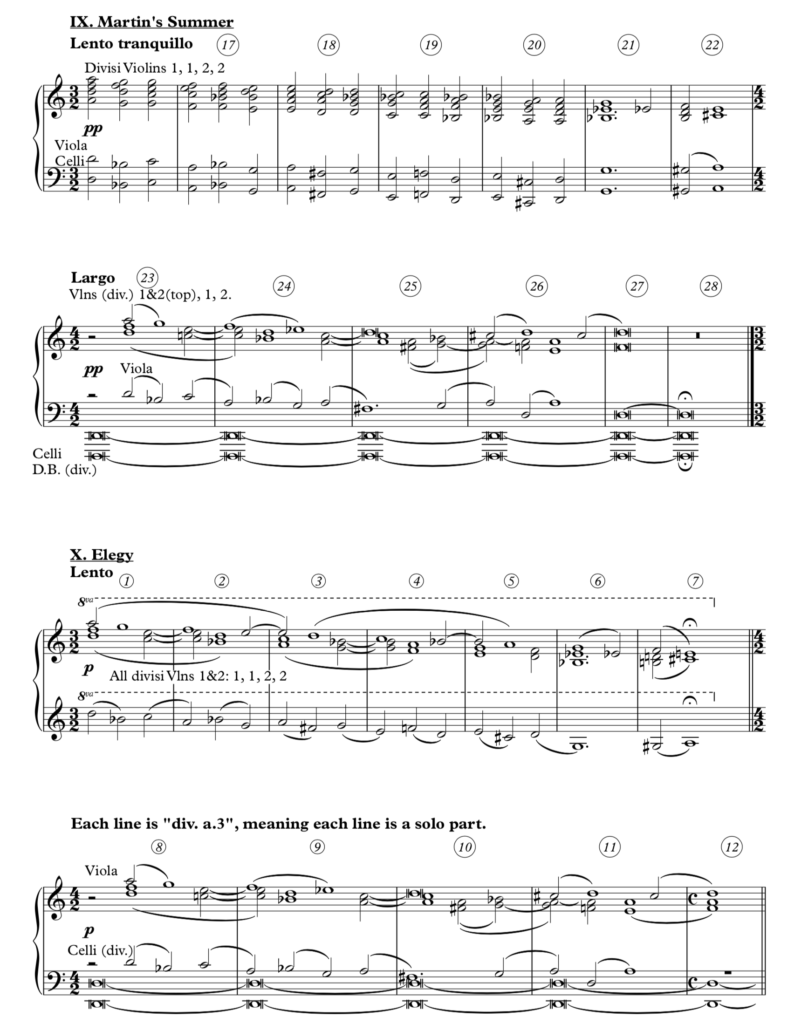

The second reorchestration example that I want to look at is the brief chaconne style idea that Herrmann uses twice in the last couple of cues, “IX. Martin’s Summer” and “X. Elegy”, two of the longest in this episode’s entire score.

(I call it the chaconne style idea purely for labelling purposes, the sequential bass idea reminded me of ground bass.)

Split into two parts, the similarity of the A and B portions of the idea are very similar, using subtle changes to the harmony and bass. Each idea is used twice, with little change to the harmony and the bass line. The highest line, not so much a melody as opposed to a harmonic voice, does not change at all. Instead, Herrmann creates variation through orchestration, using distinctions of solo-divisi, different string instruments, bowing (which alters the texture) and register.

To demonstrate these changes, I have created a table highlighting each idea with a description of its orchestration. In Martin’s Summer, part A1 on the table, the sound is one of the string orchestras, with each part having at least two players on each line. It is the most distinctive variant, in my opinion, as it uses a detaché bowing that alters the perception of the music’s texture. Rather than feeling contrapuntal, it feels more homophonic as the strings move together. It’s impressive just how much a simple change like that alters the feeling of the music so extensively. To me, the setting comes across as more reverential than A2, which is more emotional.

A | B | |

1 “IX. Martin’s Summer” | 1st Violins: Divisi (3 a part) 2nd Violins: Divisi (2 a part) Viola & Cello Sections 8va unison Detaché bowing | 5 Violins on top part (3 1sts; 2 2nds) 3 + 2 Violins on inner parts. Viola Section Unison on Bass line Cello & Bass section on Pedal |

2 “X. Elegy” | Divisi 1st and 2nd Violins only (High register. All of them would be on their E-strings for the first few bars.) | Solo Violas (divisi a. 3) – Top and Inner lines Solo Cello on Bass line Solo Cellos 8va unison on Pedal |

Table 2: Orchestrations, using strings, of similar ideas in the final two cues of Walking Distance (“IX. Martin’s Summer” & “X. Elegy”)

The emotional quality of A2 likely comes from the use of high violins, moving with more independence than the detache A1 idea. Each violin, at least for the first three bars, will be on its shimmering E-string. Restrained by the mutes and piano marking, it is retrospective in character as opposed to overflowing.

The two B ideas are varied by the juxtaposition of section and solo qualities. In B1, most of the lines have a handful of players on them. Only one inner line has just two players, whereas every line in B2, including the pedal, has one player. I have discussed the concept of juxtaposing solo and section colours before, with greater detail than I can do here. In brief. it’s a subtle variance of presence and weight. I will link the relevant articles below, where I discuss this concept concerning other pieces.

- Introduction and Allegro for Strings – Edward Elgar (where I explicitly discuss presence and weight)

- 5 Variants on Dives and Lazarus – Ralph Vaughan Williams (distinction of solo-section and divisi blending to extend colour. I also speak about antiphonal positioning in string orchestras, which could have relevance here. However, I am not sure how Herrmann sets up his strings within the recording studio for this cue.)

Summary

Herrmann demonstrates a range of ways we can use orchestration to bring our pieces to life. One of these lessons is to be selective about instrumentation. Ironically, when a lot of us have unbelievable control over the music we create as composer-producers, we brush over this important decision. We seem to default to standard setups, be it templates or historical norms.

Another lesson is that we should think more deeply about the sounds we want and how they relate to the sounds and feelings we are trying to create. I liken the fortissimo con sordino string sound to shouting in a coffin. It is haunting. We can feel the players are playing loudly, even aggressively, but their sound is restricted. How might this make an audience feel? Or the sound of flautando?

Lastly, we’ve seen how orchestration is not only vital in bringing our music to life but useful too. (A crafty skill!) Rather than rewrite material or try and come up with melodic development when it might not be needed, using different colours is a great way of extending and refreshing our ideas without reinventing the wheel.

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …