Bernard Herrmann’s “Walking Distance” is full of different orchestration and composition techniques. Last week we focussed on some of those orchestration techniques, such as reorchestration. This week we are looking at the composition. However, just like with the orchestration, we will have to be selective. Therefore, I have selected two short cues to look at in their entirety (“I. Introduction” & “VIII. The Merry-go-round”) and a third (“III. Memories”) to look at an extract only. In doing so, I will be discussing a plethora of techniques that Herrmann uses. The main two are melodic sequences, which Herrmann uses as a device for extending and developing ideas, and tension (or suspense), of which Herrmann is masterful in creating and controlling.

“I. Introduction”

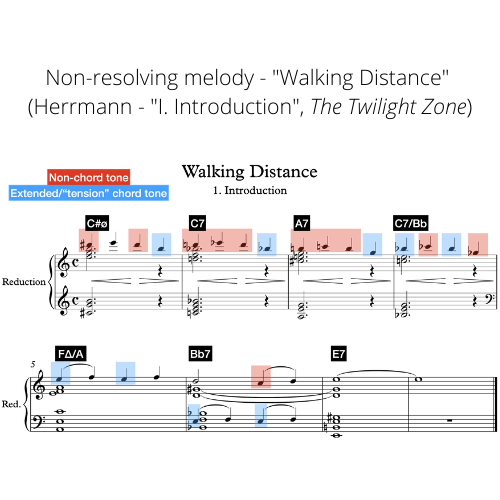

Non-sarcastically… the introduction is a great place to start as it displays a range of techniques that establish the musical language of the episode. These are melodic sequences, extended triadic harmonies and non-resolving tension tones. It also has a Lydian suspension. However, I am going to leave the suspension out, so I can focus on the others here, as there is a more extensive demonstration of this technique in a later cue.

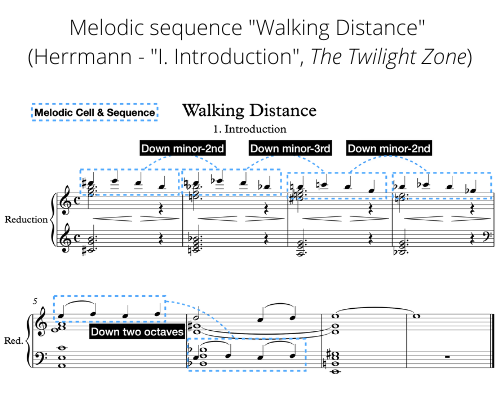

Melodic Sequence

A melodic sequence is the repetition of a melodic cell or motif at a higher or lower pitch. In musical terminology, the movement of the cell up or down in pitch is a transposition. The transposition may be a straight one, where both the contour and intervals between notes are identical, but the pitches are changed. Or, it could be that only the contour remains the same, and the intervals are changed slightly. Typically, if the composer uses the latter, where the intervals changed, it is to work with the underlying harmony or larger tonal area.

In the case of Herrmann, he uses straight transpositions in this cue and several parts of the wider score. For instance, in the introduction, each cell of the opening, four-bar, melodic sequence preserves its intervallic content. Each one rises a semitone from its starting pitch before falling to its starting note on beat 3. It then falls a major-3rd from beat 3 to 4. It is, therefore, a straight transposition between each of the bars.

On a larger scale, the melodic sequence splits into two parts. Between bars 1 – 2 and 3 – 4, each melodic cell of the sequence falls by a minor second. However, between two and three, it falls a minor third. Throughout the different cues, there is an emphasis on minor-2nds and, either major or minor, 3rds in the melody and harmony.

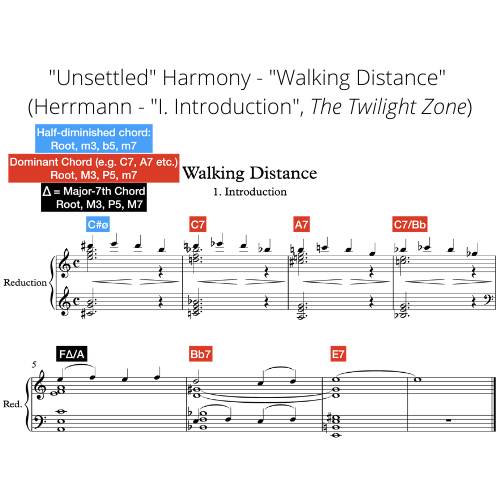

Unsettling Harmony

Herrmann regularly uses one chord per bar in many of his cues and throughout the introduction cue. He also frequently extends his triads using minor, major, dominant and diminished 7th combinations.

In this cue, he predominantly uses dominant-7th structures, which is significant as it is a harmonically unstable chord that wants, but Herrmann does not allow, to resolve. More ambiguous or contextually dependent, as opposed to dissonant, the dominant seventh chord is unstable on account of its tritone. Like the repulsion of two magnets, the tritone typically wants to resolve outwards or inwards to the root and third of the following chord, which, as a result, is usually a dominant relationship.

The introduction cue closes (bar 6 – 7) with a trademark supernatural or, more, outer-worldly M6M (major chord to a major chord progression by an augmented-4th/6-semitones) progression. By no means deathly or dangerous, the Bb7 to E7 tells us that something “not quite right” is going to happen, even if it takes time for the protagonist, Martin Sloan, and us, the audience, to realise it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYqfTcI3Ztk&t=9s&ab_channel=AnyOldMusic Paul Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897) is a musical composition based on a poem, of the same name, by 18th-century German writer Johann

Non-resolving chord tones

In addition to the rich, unsettled harmony, Herrmann adds to this feeling by having the melodic sequence that we have discussed sit dissonantly against much of the harmony. If we examine the opening four bars, for instance, very few notes are chord tones. Furthermore, most of the tones “resolve” to “tension” notes, such as the 7th.

Similar to the next cue in this article, “VIII. The Merry-Go-Round”, the shape of the melodic cell and lack of resting points, where the melody settles on notes of the harmony, is disorienting. It is like we are spinning or unable to catch our breath.

Herrmann’s harmony is incredibly considerate. While there is a great deal of tension in the melody, harmonic structures and the progression, his emphasis on major chords sets a tone that is not one, as I have said, of danger or death. If the tonality had been minor, the feeling could have been more dreadful. Setting the mood, this combination of uplifting-major-tonality with unstable-harmony exudes a depth of meaning that allows us to relax but also be on the lookout for something, as I have said, “not quite right!”

“XIII. The Merry-go-round”: cell or motif!? Melodic development, for sure.

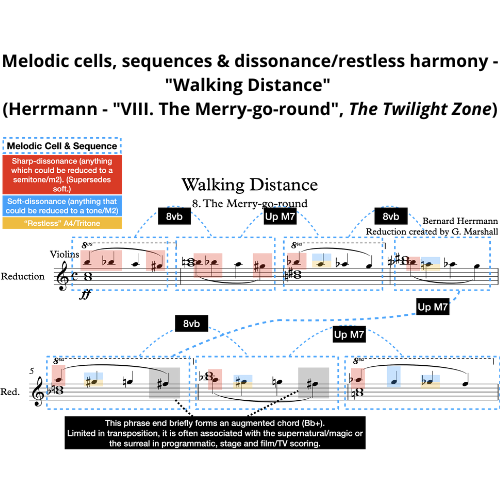

There are so many points where Herrmann uses sequential structures that I have had to be selective, picking just a few that I felt invited exploration of additional concepts. The second example, “VIII. The Merry-go-round”, is compelling, in my opinions, as it also uses some techniques of melodic development. To introduce some of those concepts, as they are useful to understand as composers, I will discuss them here. (Timecoded link to this cue.)

Similar to the “Introduction”, the piece opens with a melodic sequence. The cells themselves are characterised by a falling, four-note, chromatic cell. Presented in a high register, on the first violins, each cell is repeated an octave lower in the second violins. The sequential repetition of this pattern occurs in a chromatic stepwise manner too. In other words, every two bars, the next figure starts a minor-2nd lower than the first. Therefore, strictly speaking, the sequence follows a pattern of down an octave, followed by, up a Major-7th. (Remember we are talking about the starting note here. I am thinking enharmonically too, for some of the annotations at least.)

Similarly, in the previous examples, featuring the introduction cue, we can also see Herrmann uses a great deal of tension again, using the devices we have discussed: unsettling harmonic structures and non-resolving melody tones. For example, as well as being chromatic, as we discussed, the opening cells often start from chord extensions. In the first bar, it is a major-9th, falling to a highly dissonant minor-9th. The melody, therefore, imposes tension notes that are usually sharply dissonant (minor-2nd or a compound of that e.g. Minor-9th/Compound-minor-2nd).

(It is also interesting to note that this is one of a very small number of sections where the strings are senza sordino/unmuted.)

Melodic development: fragmentation, alteration and diminution

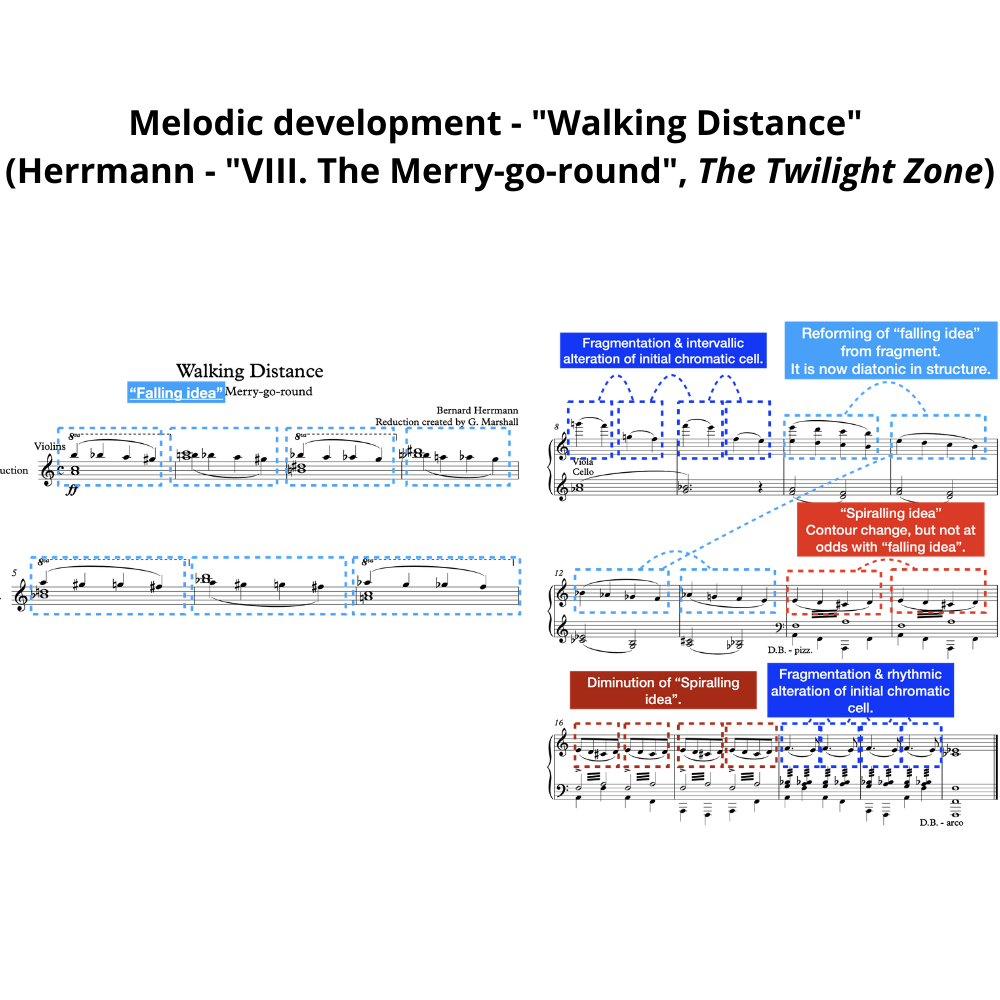

In extension to the sequences, Herrmann also deploys some melodic development within this cue. Along with a gradual accelerando across the piece, the melodic development creates a feeling of speeding up (diminution) and spiralling (altering the cues cell) out of control.

“Falling”: Fragmentation and imposing change

Fragmentation is the process of extracting a portion of a melodic idea or motif and focussing on it as an idea in its own right. Herrmann uses fragmentation in two places and is performed on what we will call the “falling idea”. At the end of the cue, the fragmented cell uses a minor-2nd but is rhythmically altered. Changed from crotchets to a dotted rhythm, it is a declamatory ending of the cue.

In bar 8 and 9, the fragmentation serves to transition our pitch material from the persistent, falling, chromatic idea. Imposing a major-2nd, it leads us into a restatement of the “falling idea”. However, while the contour remains, the intervals are a mixture of major-2nds and minor-2nds: more “diatonic” in structure.

“Spiralling”: Diminution and dynamism

The diatonic “falling idea” acts as a bridge into the “spiralling idea” (bar 14). Mixing diatonic intervals, the contour is suddenly altered, creating the most dramatic change in the cue, which is exacerbated by the rhythmic diminution of the “spiralling idea” in bar 16.

Diminution is the process of decreasing a notes rhythmic value. In a straight, consistent, rhythmic transposition, the pitches remain the same, but the note values turn from crotchets to quavers.

Audio-visual parallels: what was Herrmann thinking?

I try to focus on the music composition to ensure clarity in these articles. However, I think it is important to briefly point out that there are some parallels with the narrative and visuals at this point. After all, this score was composed for TV. Herrmann will have been thinking about this in composition as opposed to processes of fragmentation and diminution, which are valuable to us in figuring out how Herrmann uses compositional techniques to convey ideas.

The “Merry-go-round” cue comes at an integral point in the narrative. Integral for Martin Sloan, the protagonist, and us, the audience. The revelation that we have not only travelled into a nearby village, Sloan’s childhood hometown, but also back in time is mind-bending. Sloan sees himself as a child and his parents, who are approximately the same age as him. Could you imagine experiencing anything so insane?

Maddening, Sloan tries to pursue his childhood self and, also, converse with his parents. At this point, the narrative reveals an injury Sloan sustains on a merry-go-round as a child. Only, it was caused by Sloan scaring and chasing himself, leading him to fall from the merry-go-round.

Herrmann’s music replicates this falling into the madness of the situation with his chromatic, “falling idea”. Adapting the initial idea, the “spiralling idea” replicates the circular motion of the merry-go-round and the surreal shift in time and events. The choices may not have even been conscious, so we can only speculate as to whether this was Herrmann’s thinking. It seems plausible in post-rationalisation though!

An impromptu analysis of the comedic melodies John Williams created to underscore the devious, Gilderoy Lockhart, in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

“III. Memories”

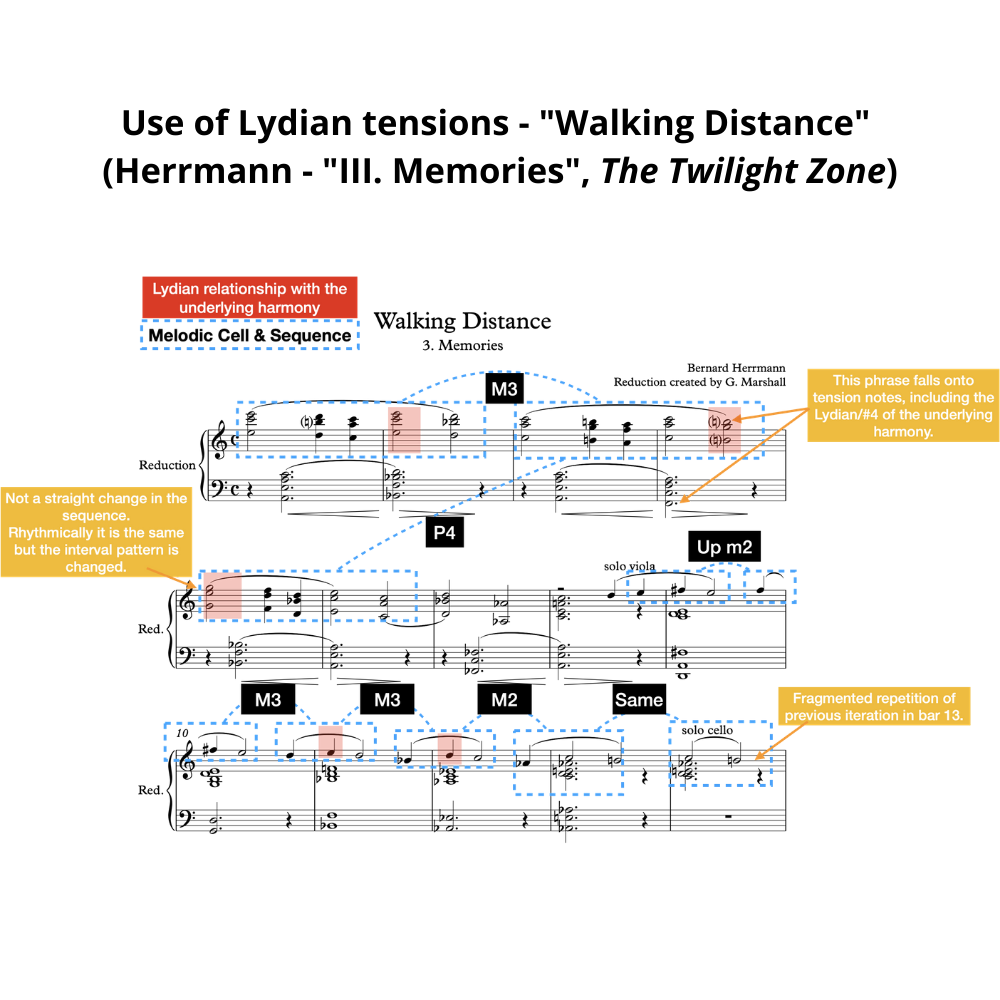

Melodic Sequences and “Sighing” in Lydian (Lydian suspension)

In the opening section of the longer 3rd cue, “Memories”, Herrmann uses two strings of melodic sequences. At the very opening, the first sequence uses an idea doubled at the 3rd and octave. The sequence transposes the idea downward by a Major-3rd and, then, by a Perfect-4th. The last iteration of the cell is not a straight transposition but is rhythmically the same and, thus, easy to see the link to the initial idea.

The second sequence occurs in the solo viola, starting in bar 8. It uses a shorter cell, but there are more iterations of the idea. After going up by a minor-2nd, it then falls successively by a Major-3rd, another Major-3rd and a Major-2nd. The last iteration of the cell is a fragmented echo, performed by the cello.

Lydian and Nostalgia

The descending quality of the sequences has a different effect in this cue. Rather than falling into madness, possibly because the phrases are more drawn out and the tempo steadier, there is a feeling of melancholy. Many of the harmonic tensions, some of which Herrmann uses as resolving suspensions, some of which he leaves hanging, add nostalgia and sentimentality to this effect.

Herrmann, to invoke feelings of nostalgia and past “memories”, uses Lydian tension notes. In bar 2 and 5, for instance, the melody either falls or rises to a melodic note that is the #4/#11 of the underlying harmony. E-natural, in bar 2 (and 5), for instance, is the raised fourth of Bb, which would have an E-flat in standard major (or minor, even). Likewise, in bar 4, F-major ordinarily would have a Bb. However, the melody falls to a B-natural.

Using an appoggiatura style melodic tension in the later sequence, with the solo viola, Herrmann conjures the same effects, extending them across the cue. He also includes other tension tones, such as the Major-7th (F#) in bar 10.

The Broader Takeaway

I think the broader takeaway from this extract is that mixing up tension and resolution adds to the overall complexity of the music. While simply deploying a lot of tension can create intensity and suspense, Herrmann resolves some here and leaves others to stay with us. The result, therefore, is more one of yearning. In this case, yearning for the simpler times that we can relive only in memory.

summary

Thinking about the larger-scale form of a score can easily be overlooked. Yet, the power wielded by media composers in determining what information, however precise or ambiguous, to reveal, or even extend, is immeasurable.

In this article, we have looked at melodic sequences as an economical means of extending and developing ideas, along with two types of tension. One type is that, which frequently accompanied by harmonic instability and dissonance, was used to create suspense. The other, using Lydian and some resolution, evoked emotion.

As I said in the previous article on orchestration, time is of the essence. We all want to put our best foot forward, but doing so requires we manage our time effectively. Time management is one answer to that. However, that’s only any good if you can do what you need to in the time you can allot. Crafty skills, such as reorchestration (in the previous article) or reliable, efficient means of extending your ideas, means you can turn a little into a lot. Turning a little into a lot makes allotted time productive.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …