Late in 1932, Sergei Prokofiev was approached by the Saint Petersburg (formerly Leningrad) based film studio Belgoskino Studios and commissioned to score their upcoming film Lieutenant Kijé. To be produced and released in 1933, it came at a time where Prokofiev, who lived in Paris and had been away from his native country for nearly a decade and a half, had been gradually reintroducing himself into Soviet-Russian cultural life as a performer and composer. Given the popularity of film as a medium, the opportunity to score a movie was personally significant to Prokofiev as it would be a substantial boost to these reputation-building efforts.

A Superly Duperly Brief Summary of the Film’s Plot

The film, Lieutenant Kijé, is often defined as a satire on bureaucracy and involves the creation of a non-existent person called, Kijé. An army clerk, who was listing names for promotion, accidentally writes the name Kijé and does not have time to change it. Eventually shown to the Emperor, the Emperor is drawn to Kijé’s name and asks for Kijé to be presented to him the next day. To cover up a series of blunders so proceeds a series of events that involves the further promotion, flogging, banishment (to Siberia), wedding and funeral of the Lieutenant, then Colonel, and then General(!) Kijé.

From Cinema to Concert Hall: the challenges of arranging

Lieutenant Kijé was arranged as an orchestral suite the following year, in 1934. However, according to Prokofiev himself, the arrangement of the suite was not an easy task. Captured by Shlifstein in a collation of autobiographical sources, Prokofiev says:

“The following year I made a symphonic suite out of the music [referring to Lieutenant Kijé]. This gave me much more trouble than the music for the film itself, since I had to find the proper form, re-orchestrate the whole thing, polish it up and even combine several of the themes.” (Sergei Prokofiev: Autobiography, Articles, Reminiscences. 2000:83)

Prokofiev alludes to one difficulty here. The film score is insubstantial. The cues are often short, not lending themselves to what we might call a copy and paste job. In other words, the cues could not be taken as a complete or near-complete movement, meaning the music needed to be, as Prokofiev exclaims, reformed and embellished.

Composed for the film The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Bernard Herrmann’s science-fiction score has a lot to teach us about composition …

Simple vs Significant: Prokofiev on the “light-serious”

Another possible reason for the challenge Prokofiev faced in rearranging the music, beyond the musical material itself, is a sensibility regarding his target audience. Referring back to my introduction, the notion of cinema as a popular media form was something Prokofiev was acutely aware of. Furthermore, as I also said, he wanted the music to appeal to the broader audience of the film. Prokofiev needed to be appreciated as a composer, and to do that, perhaps quite uniquely in Soviet Russia, at this time, successfully composing music for different mediums was something of a requirement. And, perhaps less uniquely, success was measured intangibly by public perception.

Further contributing to the effect on the reputation that Prokofiev was trying to cultivate, the suite needed to also strike a balance with audiences. Prokofiev wanted to please the film audience, providing compelling film music. However, he also needed to please and, at the very least, appease his existing and new music followers. These music lovers would likely have different tastes and criticisms for what they hear. So, especially for the arrangement of the music suite, the music needed to be nuanced enough for them to appreciate it. In other words, he did not want to ostracise any of his listeners, who might then label him as a particular kind of composer. He needed the music to be accessible.

Demonstrating a sensibility for what he intuited in Russian cultural society at this time, Prokofiev identifies two types of music. He does not specify the name of the first. However, judging by the name of the second, “light-serious”, we can assume it would be something along the lines of serious, significant or art music. This is what he says about “light-serious” music:

“It is by no means easy to find the right idiom for such music. It should be primarily melodious, and the melody should be clear and simple without however becoming repetitive or trivial. Many composers find it difficult enough to compose any sort of melody, let alone a melody having some definite function to perform. The same applies to the technique, the form—it too must be clear and simple, but not stereotyped. It is not the old simplicity that is needed but a new kind of simplicity. And this can be achieved only after the composer has mastered the art of composing serious, significant music, thereby acquiring the technique of expressing himself in simple, yet original terms.” (Sergei Prokofiev: Autobiography, Articles, Reminiscenes. 2000:99-100)

Idiomatic composing

I find many of the remarks Prokofiev makes here to be intriguing. For example, “the right idiom”. When I think about idiom and idiomatic writing in terms of music composition, the first place my mind goes to is idiomatic writing for instruments and performers. Does the music I have written suit the instruments it is for, or what instrument in my ensemble is best suited to each part of the music I have written? In this instance, however, Prokofiev is talking about the audience and the context in which the audience will be engaging with his music. Is it idiomatic to the audience and where they are viewing the performance?

If you are enjoying this article, then you should consider subscribing to Any Old Music’s emailing list.

Simple within the bounds of significant

The other point Prokofiev makes, regarding the need to have written “serious, significant music” to be able to express oneself “in simple, yet original terms”, I find to be a compelling point. It is not a point that I think is wholly true or false.

The part of the statement that I think is true is that to write something “simple” and “original” requires a firm grasp. So often I marvel at just how simply composers within the Western Classical and Hollywood musical canons, who we thus consider eminent, compose.

To explain my thinking, an analogy I would like to draw is that of a javelin thrower. If I were to attempt to throw a javelin, 20 metres would likely be a significant throw. On the other hand, as a competent amateur and, undoubtedly, a professional, the challenge would likely be to ONLY throw the javelin as short as 20-metres. A significant throw for the professional, olympian, would be 3 or 4 times as much. At 20 metres, therefore, it would be more a case of trying to accurately throw that length, which is the difficulty, perhaps, that Prokofiev alludes to. Accuracy, not range!

On the other hand, referring to the previous point regarding idiom: what is musically significant? For Prokofiev, he means, if not the Avant-Garde, then the peripheral fronts of contemporary classical music. However, at the time of Prokofiev, the musical similarities between idioms or disciplines of music composition, such as film, opera, ballet and other concert styles, were not as far detached as they are today. Western film scoring, in its infancy, was borrowing much of its technique from the stage and symphonic music. Now, the different mediums are much more their own disciplines.

To write serious and significant film music is not so clear cut as writing serious contemporary concert or popular music. Of course, skills do overlap, and the borrowing of ideas and techniques from different idioms can be a lucrative means of standing out. However, rarely are those things at the very boundary of the idiom from which they are plucked and applied in a relative field. The ideas are, referring back to competency, better understood.

Perhaps I am wrong though, what do you guys think about what Prokofiev has said? And, by extension, what I have discussed about Prokofiev?

Composition Analysis

Overview

Troika is the fourth movement in the Lieutenant Kijé Suite. In the film, the music underscores a sleigh ride. The sleigh is drawn by three horses, which is where the Russian term troika comes from. (Link to point in the film.) At the point in the movie where Troika cues, one of the Emperor’s aides returns from Siberia “with” Kijé. Having been sent to retrieve the banished Lieutenant Kijé, the Emperor remains unaware of Kijé’s non-existence and wants to make him leader of his guard, promote him to General and have him marry his daughter.

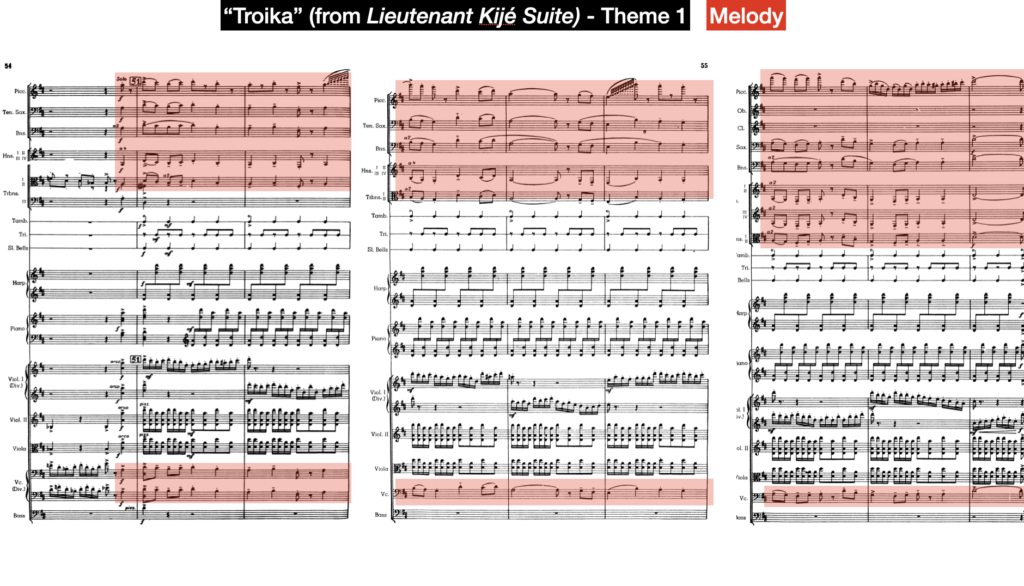

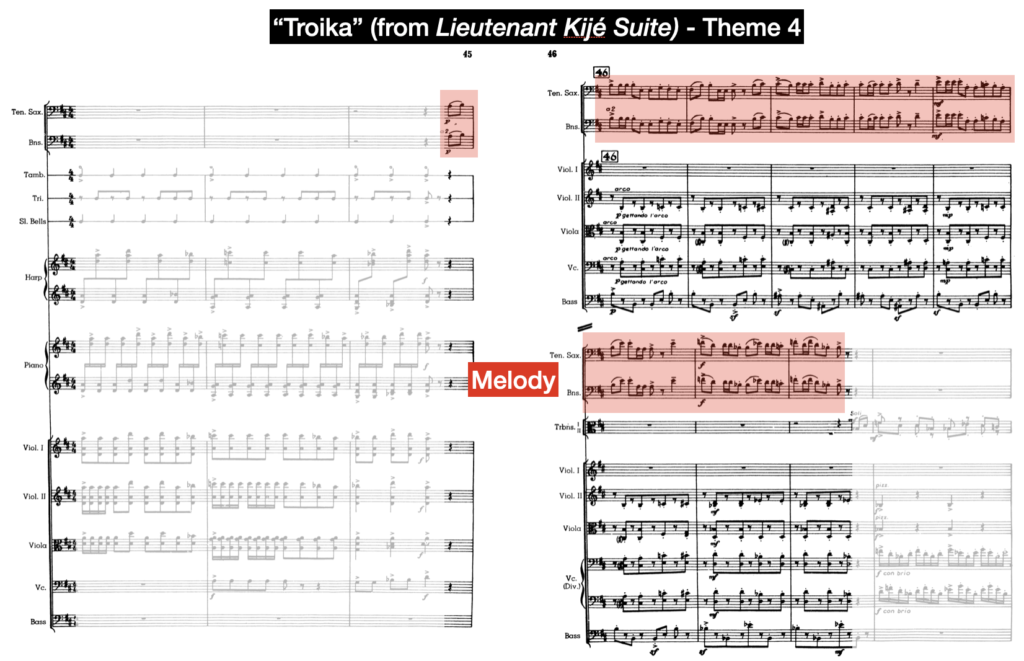

In the film, the cue from which Troika originates is much shorter and features a solo voice that sings themes that I label as 1 and 3. Theme 2, which is a version of Kijé’s theme, is the same in both versions, performed by pizzicato strings, harp, percussion and piano. Unless cut from the film, or appearing somewhere in sketch form, the fourth theme appears to have been composed specifically for the suite.

A complete analysis of Nocturne No. 19, looking at form, structure, harmony and melody.

Melody and Arrangement

In keeping with Prokofiev’s assertion that idiomatic “light-serious” music be “primarily melodious”, the introduction and codetta––which open and close the piece––are homophonic settings of theme 1. Beyond this, each section of the piece is a distinct theme. Each melody forms what we might call modules, and Prokofiev can lay down each of these modules of the arrangement in a simple but well-crafted manner. For example, there is no reason we could not take out some of these modules and still have an intact movement. Or, conversely, we could slot some repetitions of the modules into the piece to extend the movement, for that matter.

Excluding some orchestration changes to theme 1, each repetition of themes 1, 2 and 4 is the same. Moreover, theme 1’s changes only occur towards the end, involving the addition of a piccolo to unison tenor sax, bassoon and cellos, three then four octaves above the melody. The piccolo is used humorously throughout the score as a militaristic reference.

Theme 2, as I have said, is Kijé’s theme, which emerges subtly out of the accompanying texture to theme 1. In other parts of the score, it is frequently performed by the tenor saxophone.

Theme 4, is the newly composed theme, which does not appear in the film. Appearing twice, it is performed by tenor sax, but with two bassoons doubling, rather than one bassoon and celli, like in theme 1. We will be looking at the harmony of this section later.

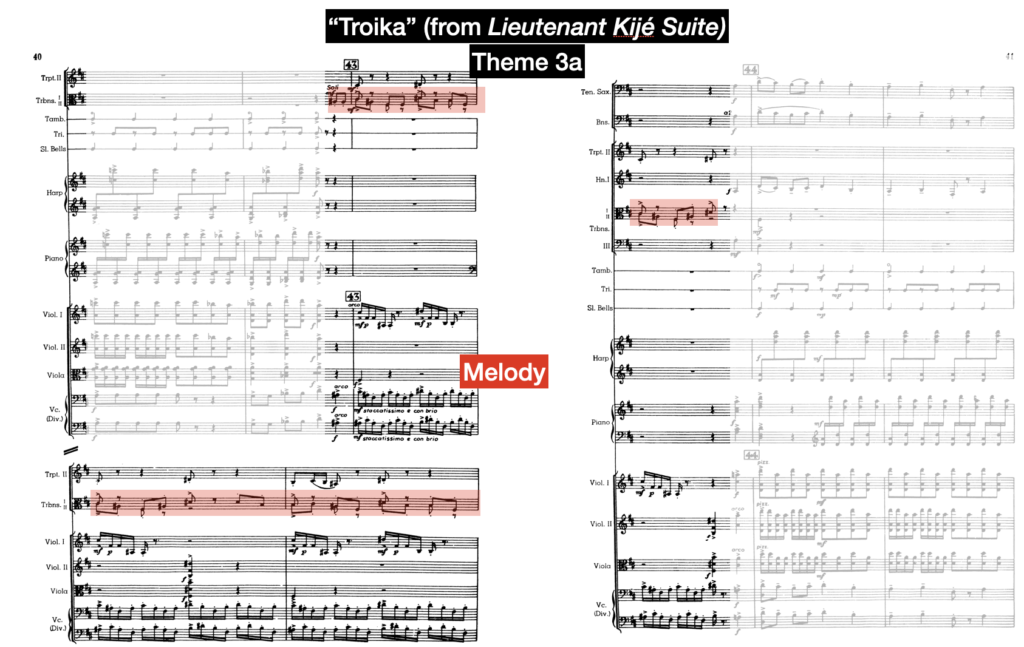

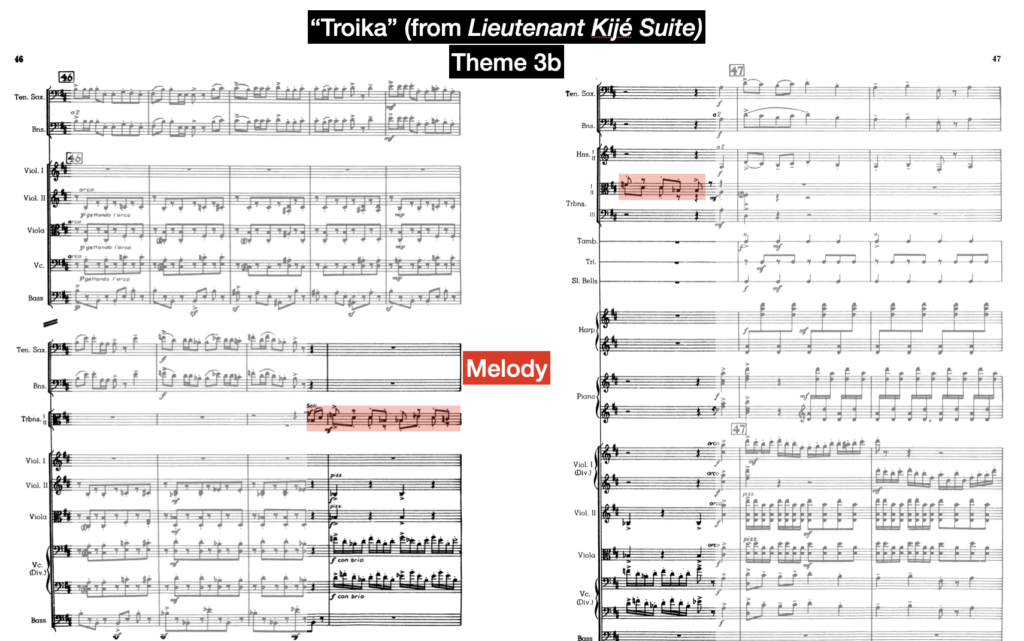

Theme 3, compared to the others, is the only varied melody. Already a short idea, one way in which Prokofiev varies this theme is by altering its length between 2 and 4 bars. Moreover, Prokofiev ties tonal changes to these modifications in length, so that we may define each as theme 3a and 3b. Theme 3a is four bars in length and in the key of B, while theme 3b is two bars long and in the key of Bb.

Albeit a short idea, I like how Prokofiev presents the two theme 3 ideas. The broken, dove-tailed trombone line adds weight and emphasis to specific notes, which I think comically colours the line. Furthermore, the heterophonic way in which other instruments, such as the divided cellos provide harmony, but skitter around the melody is a clever texture. (Not that Prokofiev needs a pat on the back from me. But kudos anyway, Sergei.)

Tonality

Tonally the movement is constructed around a series of juxtapositions. These juxtapositions occur around the modular design concept introduced when discussing melodies. Each module boasts a different modality or tonal centre. For example, theme 1, while not overly asserted, is distinctly D-major. Whereas, theme 2, or Kijé’s theme, the tonality is an implied D-minor. (What I mean by “implied” here is that we intuit D-minor through the use of C-natural and B-flat. However, we never hear an F in the harmony or melody.) Theme 3 is the only module in which there are two different keys. Hence my decision to label one 3a and another 3b. 3a is in B-major, while 3b is in Bb-major. Finally, theme 4 orients around a tonal centre of B and Bb, implying a minor modality for each. Furthermore, how these two keys, B and Bb, are presented within this section is juxtapositional. We will take a closer look at the harmony of this section soon.

As we can see, there are tonal shifts between the themes, reinforcing the modular design. Moving from D-major to D-minor, then to B-major and so on, Prokofiev uses direct modulations in tonality to maintain interest.

Harmony

As well as tonal juxtapositions, Troika boasts juxtapositions of harmonic structures too. What I mean by this is that we get themes that use different chordal sonorities. For instance, one section might use chords constructed by thirds, while another might use chords made of seconds. Furthermore, sometimes Prokofiev will even use functional tertiary harmonic progressions, as he does in the introduction and close of the composition.

Adding further to the modular nature of the movement, themes 3a and 3b are tertiary, with the celli predominantly in thirds and the melody itself outlining the harmony. For themes 1 and 2, we get more static harmonic structures built around open-string multiple stops.

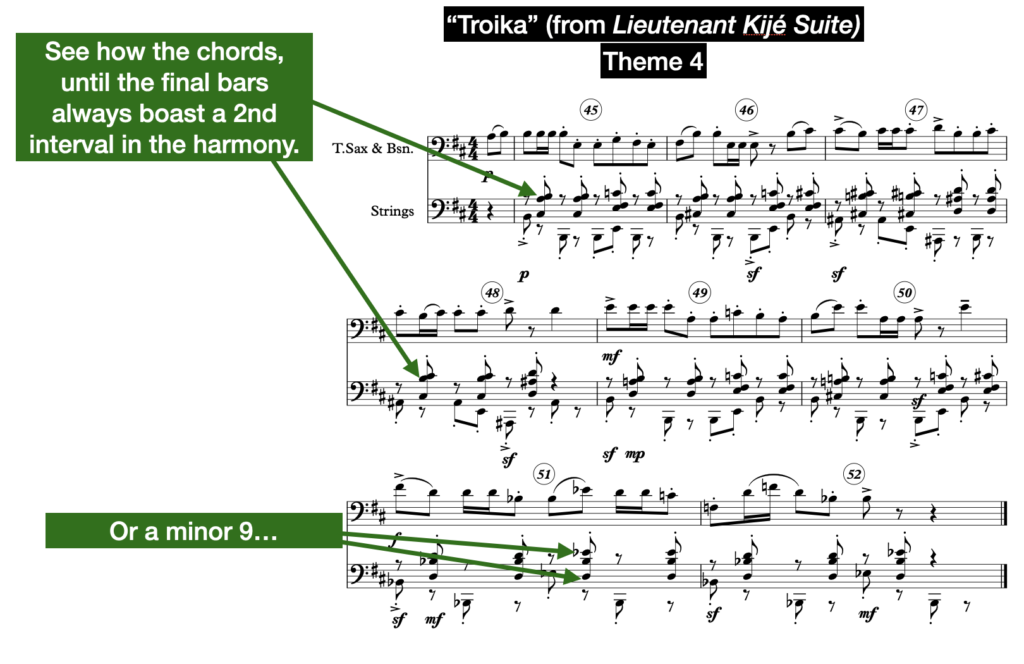

Theme 4, on the other hand, uses a combination of what we might call secondal and added-note chord structures. In these sections, the tonal centre is asserted by concise pitch sets and the repetition and emphasis of particular notes. For instance, if we take bars 45 and 46, we can see Prokofiev only uses the pitches B, C, C#, E, F#, G and A. Excluding C-natural, the pitches are the scale of B natural minor, without the third. Moreover, note B is emphasised, through repetition, by both the melody and bass.

On a larger scale, the secondal structure comes through in both the chordal progression of the two bar phrases and then the juxtaposition of these phrases. For example, the roots of the two chords in bars 45 and 46 are B and C. Meanwhile, the starting roots of each phrase are either B, A# or Bb.

Theme 4 is more complex and dissonant in quality compared to others. Furthermore, it seems to have been composed specifically to extend the cue into a movement for the suite. Upon reflection, is this what we might call a form of musical marketing? This section, which seems to have been added purposefully by Prokofiev, is tailored more to those musical individuals who would be tuning into or attending a musical performance of a concert suite. Is this a subtle wink to those listeners who might appreciate secondal harmonies a little more?

Close

Today we have taken a closer look at the movement Troika from Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kijé Suite. However, beyond the techniques of composition that we have unearthed, such as the concept of a modular arrangement, the emphasis of theme and the use of various harmonic structures, there is a lot to learn as composers more generally from Prokofiev here. While I think one should always write for oneself as a creator because at least you can guarantee one person will like what you have done that way. There is a definite need as artists, particularly professionals and those composing for popular idioms, to consider the contextual aspects of our work. In part, this could be aesthetics on a grand scale. However, I am thinking more in terms of a project by project basis and the creation of music for specific contexts such as a film or concert commission. Sometimes we might need to try and make our music idiomatic for certain settings as well as players, altering or emphasising parts of our language. I guess, in a way, sort of how we might adjust how we speak in certain contexts. What I say to my mates in a group WhatsApp, for instance, would not be the same words and phrases I say to my parents or grandparents. In this way, as Prokofiev does here, we might use less dissonance and more triadic language. Or, maybe even functional harmony, if we were writing music for a particular group, medium or event. Conversely, for a different context, we might use more challenging techniques and language. In essence, we need to be mindful of who and what we are writing for, assuming we care about them.

If you have enjoyed this article, then you should consider subscribing to Any Old Music’s emailing list.