If someone were to ask me what my favourite film was, I think I would be hard-pressed to answer with something other than 2010’s How to Train Your Dragon. The reasoning is vast should reason be required for doing something like declaring a favourite film. However, in one sense, my choice boils down to how the story and the presentation of that story pulls and pokes at different emotions. How to Train Your Dragon makes me smile and laugh, scares me, makes me angry, and it makes me hold back tears with incredible British restraint and mentally damaging bravado. Most importantly, however, it boasts a masterful score that not only has out-and-out bangers, but adds to the story through its use of harmony, orchestration and leitmotifs.

Today I want to focus on the very opening to How To Train Your Dragon‘s soundtrack as, recently, my wife bought me the How To Train Your Dragon score from Omni Music Publishing (no affiliation) for my birthday. And, this purchase led me to discover, via the publisher’s generous analytical preface of the soundtrack, that there are two versions to the opening of the introductory cue of the film: “This is Berk”. According to this preface, the filmmaker’s felt Powell’s original opening had a “dark tone” that was “not right for the picture”, and, therefore, “the composer [John Powell] wrote an [1M2Alt, “Berk Intro”] alternate ‘warm’ version” (How to Train Your Dragon in full score, Omni Music Publishing, 2020:vi) in response.

The 1M2alt version of “This is Berk” is startlingly different to the original version. Which got me thinking: it’s easy to forget that film scores come into being through collaboration, with directors and producers attempting to articulate the music that they believe matches their creative vision. Therefore, we have a rare opportunity to see where those conversations and articulations can lead in musical terms. I do not know what was said or how the feedback was articulated, beyond what is outlined in Omni Music Publishing’s preface to the score, regarding the dark tone and the responsive composition of the alternate “warm” version of the cue that came to be the film’s score. However, let’s assume the filmmakers did ask for the score to be “warmer”, “lighter”, or “less dark” sounding in some form or other. What does this mean in musical terms? How does John Powell respond to that feedback, and how does he create a warmer feeling to the music?

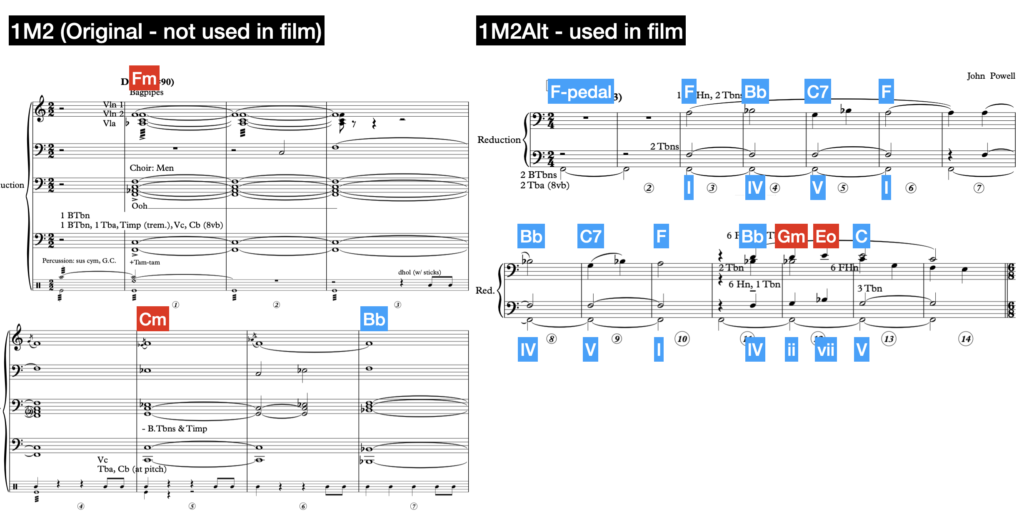

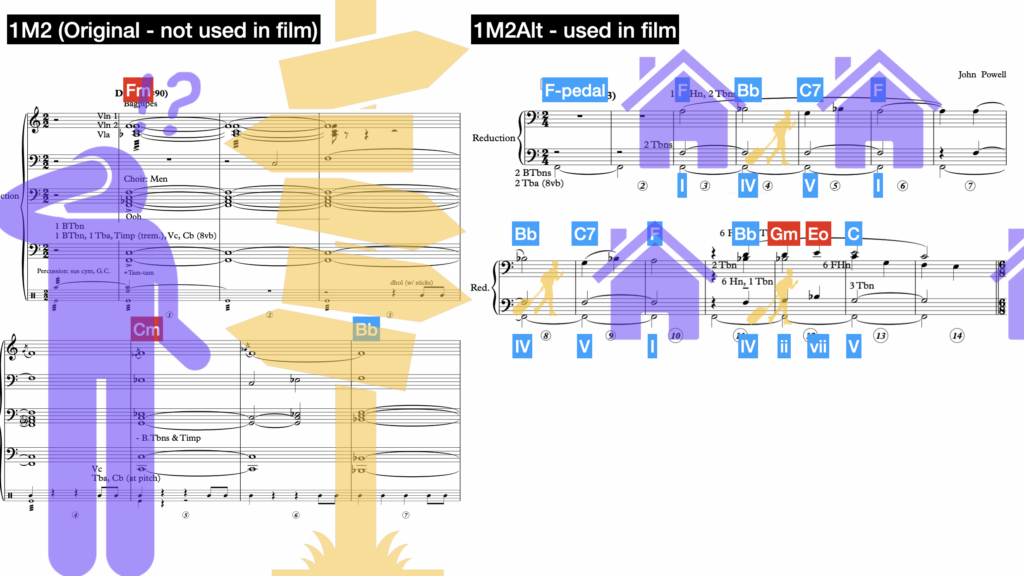

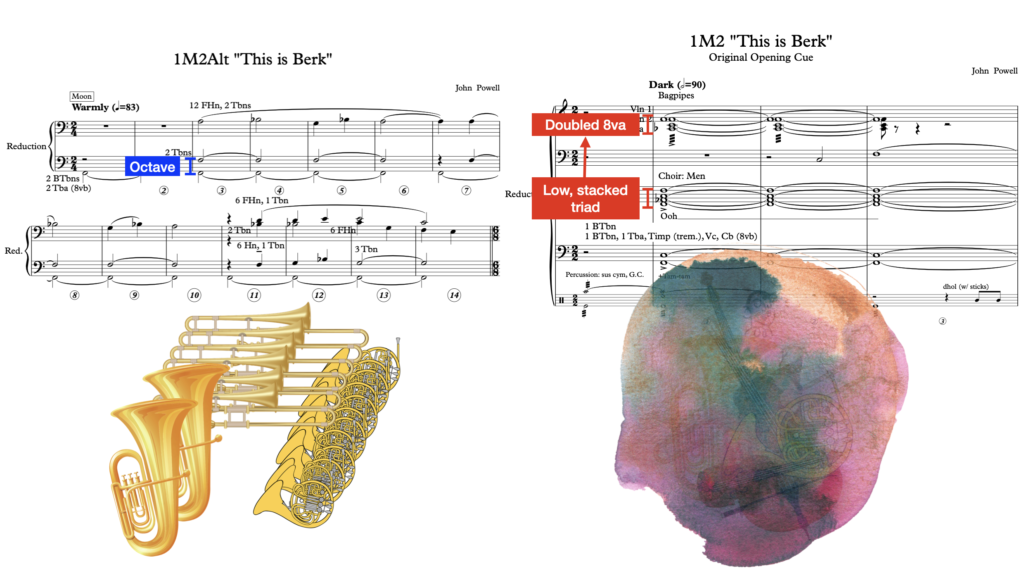

Score Reductions that this article is analysing

Harmony: Major vs Minor

Starting first with harmony, in the “Tranquillo”, 6/8 sections of the two “This is Berk” cues, bar 19-36 for the original and bar 15-33 for the alternate version, the cues are harmonically the same. In other words, while orchestration changes for the 6/8 sections the chords and progressions remain unchanged. In the very opening to both cues, however, the harmonies are very different. The alternate version is in F major, while the original version is in F minor, with tinges of F-Dorian.

The original version of “This is Berk” opens with a dramatic low F minor chord. This F-minor chord is static and only changes to a different chord, C minor, in bar five. Moreover, it is not until bar seven, where we have our first major chord, a B flat. Contextually, this B-flat does little to assert itself or the F-minor as the home key, bringing a Dorian flavour. Moreover, the B-flat’s relationship as a sub-dominant or tonic to F creates further ambiguity. We could be in F or Bb here. The very opening, while emphatically minor, is uncentred.

In contrast to the original cue’s minor tonality, the alternate version opens with a tonic pedal on F. Moreover, the melody quickly asserts F-major by entering on A3, its rich mediant tone. It is not until bars 11 to 14 that we have a clear triadic progression that establishes F, but the melody itself, before this, does enough, on its own, to make us feel at home and unabated by the combination of pitches we are hearing.

Stability vs Instability (Harmony continued)

In effect, we have a combination of harmonic procedures that make the music “lighter” in the alternate version’s opening. One is the simple cultural perception of major and minor: major being uplifting and minor being downbeat. This is not to say that major and minor cannot be the opposites of these things, but that they tend to conjure these emotional responses. Powell uses the optimistic qualities of the major mode to project a lighter opening.

Harmonic progressions, just as tonality can make us feel happy and sad, tend to make us intuit a sense of stability, transience or instability. In the original film version, we have instability, as the harmony is not goal-driven. In the alternate version, on the other hand, the harmony is stable as the melody moves away but returns to a note of the primary triad, F-major. In a sense, both are transient, and it is this transcience that gives a sense of home and, thus, a place of stability. Or vice-versa. The original, for instance, progresses, but there is no goal. The alternative version, however, goes for a brief but planned trip before returning home. In completing those trips, the original is nomadic while the other settled. You can only return home if there is a home to go to.

Orchestration

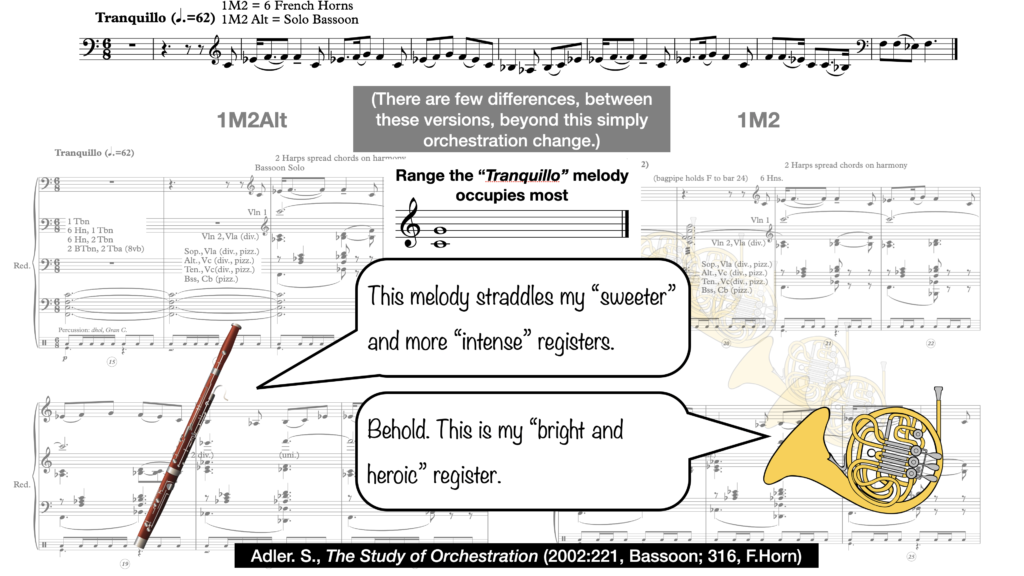

Another area that John Powell addresses to make the alternate cue “lighter” is orchestration. Again this is most obvious in the very opening of each cue. However, Powell also adjusts the orchestration slightly at the beginning of the Tranquillo or six-eight section. Swapping a six horn soli for a bassoon solo at the beginning of the Tranquillo is one example of how Powell, again, uses clarity and, in effect, orchestrational lightness to lighten the character of the cue. Along with the simple interchanges of instruments, Powell also makes changes to the use of doublings, registers and voicing, particularly in the very opening of these two cues, to create the music that the film producers would like. It is these aspects of orchestration that we will look at in this section.

Section/group vs Solo/one

As I’ve mentioned already, Powell switches a section of six French Horns for one bassoon between the original and alternate cues. A small change, why is it significant? The reason this change is significant is, in part, its subtlety, but also the dramatic effect this subtle change has on the clarity of the music and its lightness.

Switching from section to solo has a significant impact on the sound quality of the melody in this section as it increases the clarity and, thus, the perceived agility of the timbres. If we think, for example, about six people in a group tied together, and then one person on their own, there are certain things you would expect the six people to be better at in comparison to the individual. You would expect the one person to be quicker, more coordinated and, consequently, nimbler and more agile. If you put them in a race, therefore, you would expect the single person to win. In comparison, the group of six would win in a tug of war unless the single person was a behemoth. The same, broadly speaking, can be said of a soli and solo: while a soli has greater strength, the solo feels lighter on its feet.

Light Vs Heavy

Rimsky Korsakov identified this comparison of unison combinations, whether different or the same instrument, putting it differently:

“The process of combining two or more qualities of tone in unison, while endowing the music with greater resonance, sweetness and power, possesses the disadvantage of restricting the variety of colour and expression.”

(Rimsky-Korsakov, N. – Principles of Orchestration, 89)

In other words, while a single instrument has the flexibility to create expression, the group does not and, instead, is endowed with greater body and volume.

Placing the horns and bassoon into their respective contexts, their accompaniments are the same. They are both supported by light sul tasto and pizzicato strings, choir, harp and percussion. In character, the accompaniment texture is delicate and light-footed too. The result, therefore, counter-intuitively, is a subdued sounding horn melody, in the original cue, but a forwarded and more expressive Bassoon melody, in the alternate version. Clearer in sound quality, the effect is inherently lighter as the texture, melody and accompaniment roles are more discernible for the listener.

The other way in which these changes and timbres affect the perceived darkness is through the different registers that the melody occupies between the different instrument choices. Looking at my trusty Adler, who offers charts on register characteristics of many orchestral instruments, we can see the melody, which ranges from Eb3 to G4 (but predominantly between C4 and G4), the French horn is in, what Adler calls, its “bright and heroic” register. In comparison, the melody sits, predominantly, in the bassoon sweeter and intense registers, where it further leans out in quality. In essence, therefore, we see another theoretical lightening of the tone quality between these two choices, which carries over into a lighter quality overall in practice. The bassoon is lean but effective in timbre, whereas the bulkier heroes of the horn section produce a darker sound.

Homogenous Clarity vs Blended Obscurity

In moving to the very opening of the two cues, the orchestration, like the harmony, is substantially different. The original uses the string orchestra, low brass, choir, percussion and bagpipes; the alternate version uses only the lower brass. The result of this, along with the register and voicing––which I will discuss shortly––is a texture that allows us to hear a clear statement of the melody along with those harmonies that we have discussed.

To be clear, this is not to say the alternate version is better because of the clarity, but that it produces a different effect. In orchestration, one way in which we can create effects is by doubling instruments and altering their collective timbre. Doubling, particularly at the unison, can lead multiple instruments to imitate the sound of others, create individual colours or produce sound effects. Doubling, therefore, reduces the discernibility of the individual timbres but increase their intensity and density. As is the case with the opening of the original “This is Berk” cue. As Rimsky Korsakov said, “individual timbres lose their characteristics when associated with others”. Veiled or shadowed, the effect of doubling makes the original cue vastly darker in quality than the alternate version.

In contrast to the original version, the use of the low brass choir extensively alters the sound world. Where before the F minor chord was a mass of blended sounds in a low register, the alternative version is transparently a low brass choir. With this change comes a literal certainty: there are no question marks over what we hear in the alternate version.

Voicing and register

Perhaps the most prominent contributor to the different sonorities between these two cues is the voicing and register of the orchestration. In other words, the pitch area: low middle or high, which is the register, and the span between notes of the chords, which is the voicing, dramatically impact sound quality too. For example, in the alternate version, which uses the low brass choir, there is plenty of space between notes of the chord in the lower registers. Each voice or instrument gets space to stand out, allowing us to hear each pitch more clearly. Furthermore, the spacings of these notes increase the lower in pitch or register that we go. The alternate and original versions go as low in pitch as each other. However, the spacing of the alternative version in these lower registers allows for greater clarity.

In contrast to the alternate version, the original version of the cue is voiced very close together, even in its lower registers. The result of this, exacerbated by the doubling and loud dynamic instruction, is a voicing where not only are the pitches inherently fatter in quality, but they get less space to stand out in the texture vertically. The result, therefore, is a sound where pitches and timers bleed into one another, contributing to a further fogging of the texture.

Again, this is not to say that either orchestration is better. A reversal of the cues could, quite easily, have taken place in an alternate universe, and we could have been talking about how John Powell darkened the cue to meet the demands of the film producers. It just happens that in this universe, the producers felt the lighter alternative cue that Powell created suited their creative vision better.

Close

The quality of music as light or dark, objectively, is dubious, possibly even absurd. Can we even perceive lightness and darkness in reality absolutely, let alone music? In both cases, music and life, lightness or darkness is surely contextual? Either way, in the case of How To Train Your Dragon, for example, we have a unique opportunity to observe a composer’s attempt to make music warmer or lighter. An attempt that was judiciously accepted by a jury of filmmakers.

We have gained an insight into just how the composer, John Powell, created his warmer alternative for “This is Berk”. He altered the tonality from minor to major. He simplified the orchestration by limiting doublings and using one instrumental family. And, lastly, he opened up the voicing of the harmony and orchestration as if to cast a light over a previously shadowy place. Powell does all of these things and creates an alternative that is not only a warmer or lighter opening to “This is Berk” but the entirety of How To Train Your Dragon.