Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers is an opera set on the South West coast of Cornwall, in the United Kingdom. Perhaps indicative of an incredibly cosmopolitan society during this time, despite the subject matter and Smyth being English, the opera’s initial libretto was in French. However, Smyth had difficulty securing a performance for a French-speaking audience. As a result, the first performance was given in the German language, to a German-speaking audience in Leipzig, in 1906.

Today I want to look at the opening 27 bars of The Wreckers Overture. Featuring three orchestrations of similar melodies, I want to analyze how Smyth varies the orchestration and thematic material to create an exciting curtain-raiser for her opera. Following this, I want to take a melody I composed in 2016 for a pirate exploration game and reorchestrate it for a similar orchestra that Smyth uses. I also want to try and reapply similar orchestration and composition strategies and devices that she uses too.

The aim is to create a classic swashbuckler sketch reminiscent of Golden-Age cinema. Or, at the very least, have three solid orchestrations that help us further our knowledge and skills as composers and orchestrators. Either way, I hope you’ll join me on this swashbuckling adventure!

Below is a score video of Ethel Smyth’s The Wreckers Overture (enjoy!). Today we are going to be ultra-focused, looking at the first 30-seconds.

Instrumentation

The Wreckers Overture is orchestrated for a standard arrangement of strings, with an unspecified number of chairs. However, given the period, it’s likely Smyth would anticipate a large string contingent. The table below highlights the woodwind and brass instruments that Smyth scores for.

Woodwinds | Brass |

3 Flutes (Dbl. Piccolo) 3 Oboes (Dbl. Cor Anglais) 3 Clarinets (in Bb) (Dbl. Bass Clarinet) 3 Bassoons (Dbl. Contra-Bassoon) | 4 Horns (in F) 2 Trumpets (in C) 3 Trombones (1 Bass) Tuba |

There is also a timpanist and two percussion parts. However, only the Timpani is used in the extracts that we analyse. Furthermore, the piccolo is the only woodwind auxiliary that Smyth uses in the extract that we are analysing too.

Smyth’s Orchestration

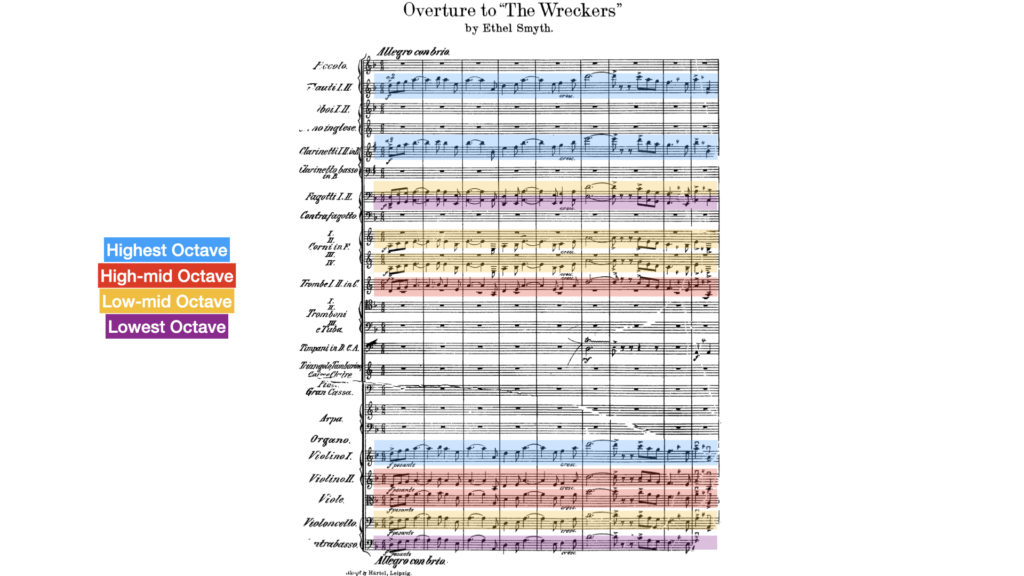

Smyth Orchestration #1: the octave unison

In The Wreckers Overture, the opening orchestration is a beautifully simple octave unison that clearly states a thematic idea that will be reiterated, in different forms, throughout the opera. However, Smyth is particular about her orchestration of this octave unison, choosing not to make it an orchestral tutti. Being specific gives her a bold opening to the overture while not being overbearing. It also means that we do not hear every colour in the orchestra at once, saving some for later.

The theme spreads across four octaves. In the highest octave (blue), Smyth uses 2 Flutes, 2 Clarinets (in Bb) and 1st Violins. In the middle-high octave (red), there is 1 Trumpet, the 2nd Violins and Violas, while 1 Bassoon, 2 Horns and Cellos take the middle-low octave (orange). Reserved for the lowest octave are 1 Bassoon and the Double Bass section (purple), while the timpani punctuates a couple of moments.

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four

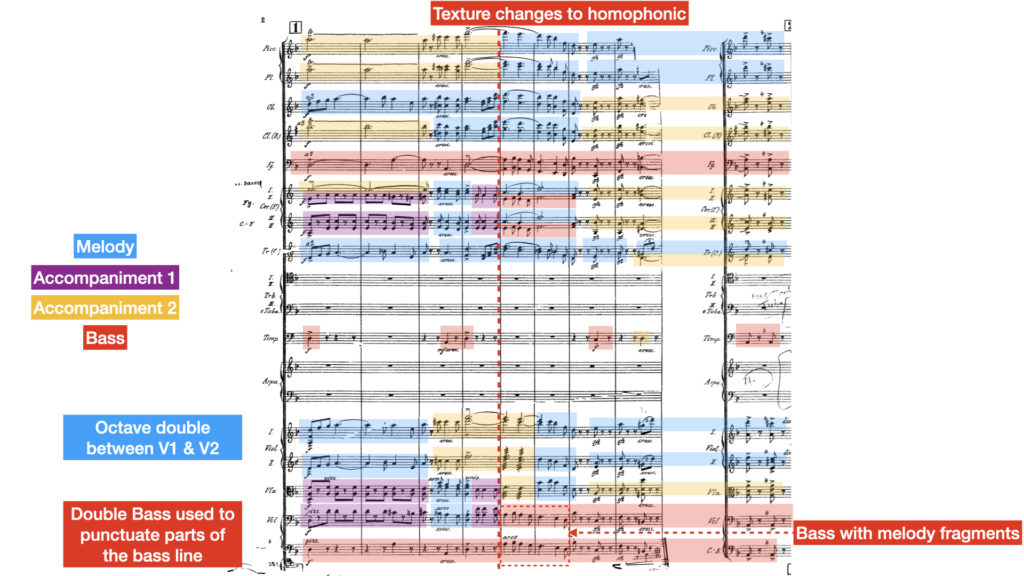

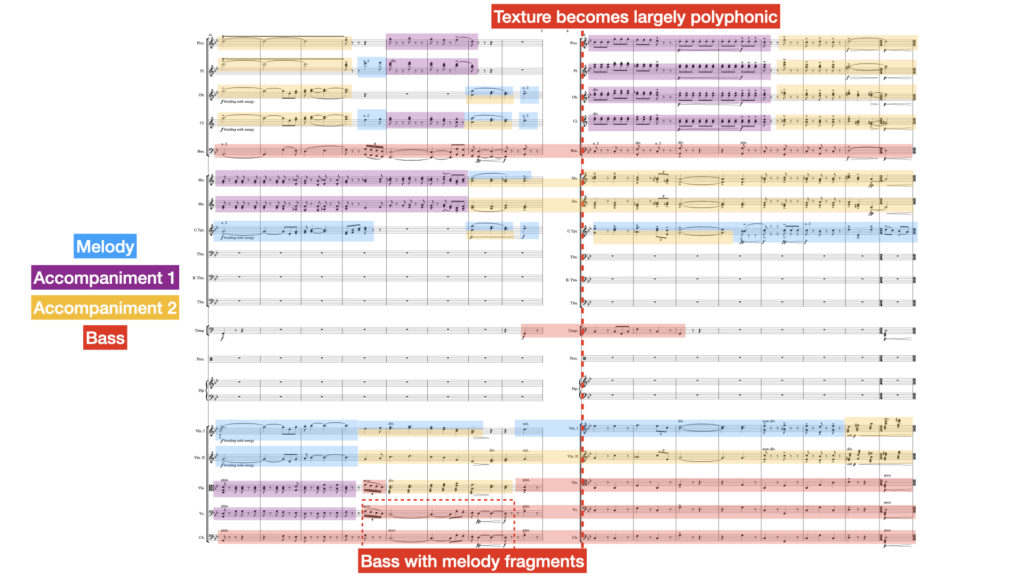

Smyth Orchestration #2: the “total” orchestra

The second orchestration is probably the most complex of the three, despite not featuring all the instruments like the third orchestration. The reason for this is that many of the instruments, momentarily, switch roles to help out certain voices within the texture. For example, the Violas and Cellos take up the melody for just four notes between bars 3 and 4, after rehearsal mark 1, before reverting to an accompaniment role. Similarly, the 3rd and 4th horns double the bass part in the 5th and 6th bar (after rehearsal mark 1). Certain instruments, therefore, switch roles based on where they find themselves and where they are needed.

This orchestration, to draw a comparison with sport, makes me think of the concept of “total football”. Not that I am knowledgeable when it comes to football. Nevertheless, football players, in a total football strategy, take up roles based on the context and position they find themselves and the game in. In this instance, instrumental lines switch roles to help a part, such as a melody or bass line, cut through the texture. However, some roles remain fixed, such as for the Bassoons and Double Basses. These instruments remain on the bass line. (Maybe these are the goalkeepers!?)

In my annotation below, the categorisation of different accompaniments, such as 1 and 2, is arbitrary. They are not specific to a particular idea and are used to demonstrate how there are differences within the accompaniment part itself. For example, the pizzicato Viola and Cello part are different to the trilling Flutes, Piccolo and Clarinets. However, both are fulfilling accompaniment roles.

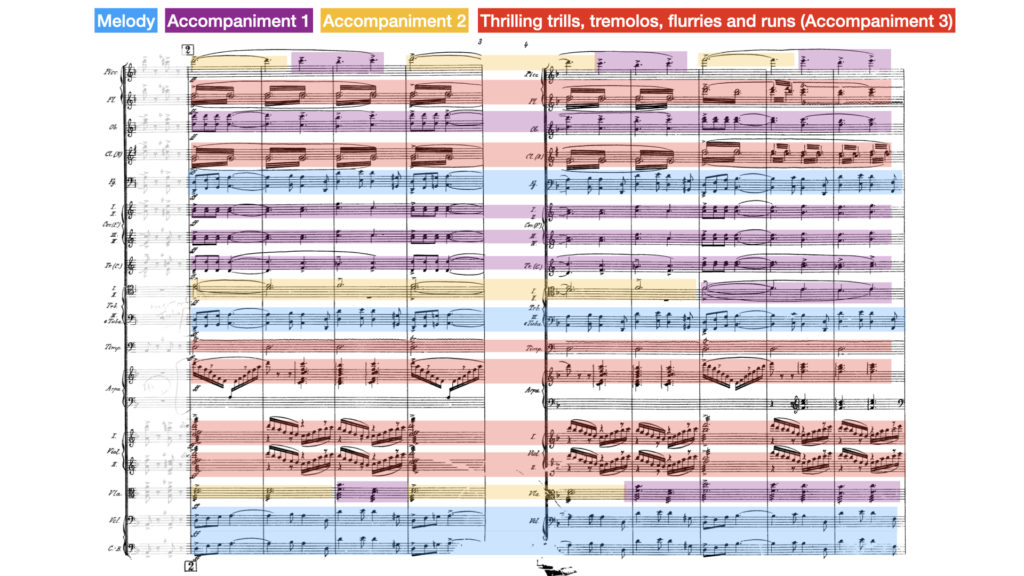

Smyth Orchestration 3: Bass Melody

In the third orchestration, the orchestra remains in four parts. However, the roles are no longer fragmented but more rigid. In other words, if an instrument is fulfilling a role in the orchestration, it does so for its entirety. Moreover, the roles are changed, and the Bass part is now also the melody line.

Given power and weight, the bass-melody part is performed in two octaves. The strident upper octave has 1 Bassoon, Bass Trombone and Cellos, while the weighty lower octave is given to the 2nd Bassoon, Tuba and Double Basses.

Accompaniment 1, like accompaniment 2, in this example, take up harmony notes. However, accompaniment 1 takes on greater rhythmic independence, while accompaniment 2 acts more like a pad, playing sustained notes. The Oboes, Horns and Trumpets provide dynamism by punctuating a 3-bar repeated phrase, which changes to function with the harmony.

Accompaniment 3, or what I call “thrilling trills, tremolos, flurries and runs”, adds to the energy and excitement of this orchestration by filling out the texture. The Flutes and Clarinets perform a fingered tremolo, while the harp and violins exchange runs, bowed tremolos and rolled chords with one another.

The timpani performs a roll on the tonic note of the key throughout this orchestration.

The Original Orchestrations (on an original swashbuckler theme!)

Before going on to talk about my orchestrations, comparing them to Smyth’s, it is probably worth hearing them. Below is a complete score video that lasts about 1-minute. It features the 3 Orchestrations on an original swashbuckler theme.

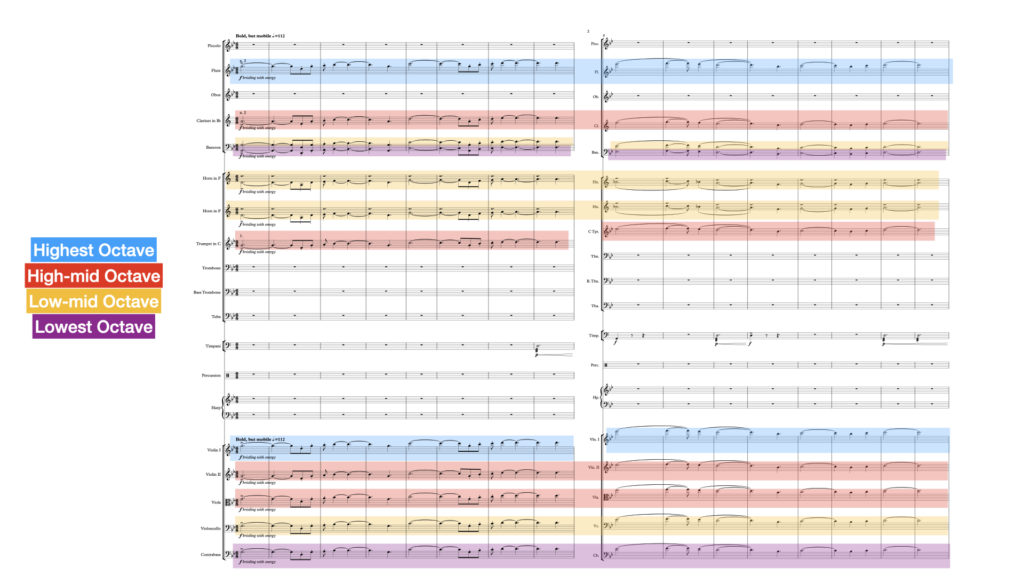

Original Orchestration #1: The Octave-Unison

The first orchestration is the easiest to compare as it was the clearest and easiest to replicate. Or, rather, it is harder to deviate from without being completely different. I copy Smyth’s orchestration, using the same instruments across the octaves, excluding a single change.

The one change I made was to drop the clarinets an octave. The reason for this change is that my melody is in G minor rather than D minor, which leads my melody into a very high register for the clarinet. A register described by Samuel Adler as “piercing” and “shrill” (The Study of Orchestration, 2002, p. 206), Smyth briefly enters this register at the high point of her melody. As the highpoint, therefore, it could be argued that the clarinets “piercing” quality was desirable here to add further intensity. For my orchestration, the context is different, and it would be in such a register for too long, to no effect. Therefore, I decided to drop both of them an octave onto the “high-mid” part.

Original Orchestration #2: “Total Orchestra”

The second orchestration is both similar and different. It is similar in that it redeploys the concept of fragmenting, or what we likened to “total football”––but for orchestra––where parts switch roles. However, I also maintain individuality by exploring the concept in itself. Essentially, there is a combination of my inherent orchestration style, Smyth’s work and an understanding of the “total orchestra” concept, which leads to something novel for me, if not wholly groundbreaking.

There are smaller-scale details that I take directly from The Wreckers, beyond the broader concept of fragmenting. For instance, the iambic 6/8 rhythmic figure that Smyth uses in this orchestration. She gives this idea to her Horns and pizzicato Violas and Cellos; I do something similar.

I also move towards a more homophonic texture as the section progresses and use melodic motifs in the bass part. However, again, these concepts are beautifully broad and have plenty of utility and space for exploration. Smyth just happens to be under our spotlight here, providing us with a means of practising orchestration.

In his 1944 Ballet for Martha, also known as Appalachian Spring, Aaron Copland uses the melody of the shaker song “Simple Gifts”.

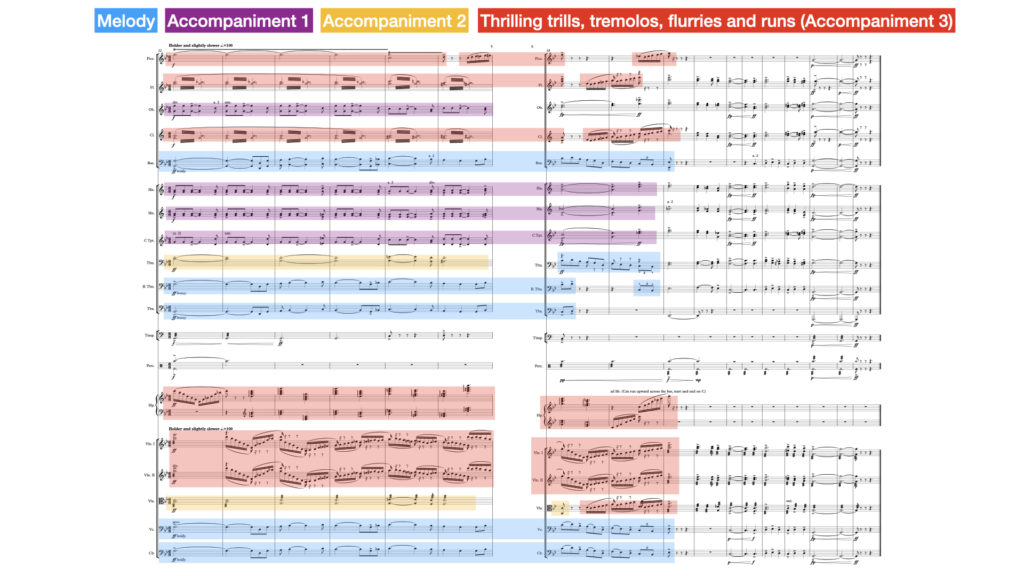

Original Orchestration #3: Bass Melody

My third orchestration is similar to Smyth’s again, as was my intent, placing the melody part in the bass, using the same doublings as Smyth. The instruments, up to where my annotations end, maintain their roles in the texture too. (My annotations end as I deviate from Smyth’s orchestration to bring the sketches to an end.)

Some compelling considerations emerged while orchestrating this sketch. I was initially concerned by the tremolo in the clarinet part, as it crossed what is known as “the break”. Falling between B-flat and B-natural, “the break” is where the clarinet passes into its Clarino register. I wondered if this would cause issues as it can require awkward key changes. However, it turns out they have additional keys to get around this issue. The problem is, the quality and security can be variable. For this reason, I decided to voice the clarinets on different chord tones, as seen in the score.

The other finer detail that is worth discussing here is dovetailing. Smyth’s Violin runs, in her orchestration, do not dovetail, whereas mine does. Dovetailing is where one line crosses over with another to minimise the gap between phrases. In Smyth’s Overture, the semi-quaver runs end before a new one starts. However, mine share a note at their respective beginning and endpoints. There is no right or wrong here. Instead, it is a matter of effect. If you want runs to be divided across parts, but seamless, then dovetail. If you need the runs to be broken apart, possibly to give a stronger sense of metre or pulse, then do not dovetail.

While on this extract of Smyth’s Overture, why the sectional-divisi? She could have simply divided the part across the two violin sections, surely? Well, again, it depends on the effect. As discussed in my article and video on RVW’s Dives and Lazarus, it was common for orchestras to have the violin sections on opposing sides of the stage. Doing this facilitated a degree of antiphonal control, much like stereo panning. It is possible that Smyth did not want the effect of having the runs sound antiphonally between the two sides of the string orchestra. Therefore, she divisi’s the runs within the sections themselves, so they continually sound from both sides.

Close: try it yourself

We have our sketches and I feel it has been a very worthwhile study. Imitation and the reapplication of techniques is an invaluable way of learning. I have an original, smaller orchestration of my swashbuckler theme. Maybe I could have made some bigger orchestrations without looking at Smyth’s The Wreckers Overture? However, if I had done that, where would I be?

You can pick up skills by practising alone. I may have stumbled across a technique while sketching these materials out. However, in trying to imitate and reapply ideas, there is a process of validation, coming from an authority beyond myself. If an orchestration works for a formidable composer like Ethel Smyth, they work for me too.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up for our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …

Pingback: Salut D'amour - Edward Elgar (Music Composition Technique Analysis) - Any Old Music