Today, I thought we’d take a look at a piece that captured my eye, because it was recently uploaded by Cmaj7 as a score video, to YouTube, and score, to IMSLP. The piece is the opening Nocturne movement from Scènes de la Fôret (Forest Scenes) by French composer, Mélanie Bonis. A composer with a far more detailed and interesting life than I can do justice here, Bonis composed across the end of the 19th century and into the first half of the 20th. Scenes de la Fôret, for instance is a later work, published in 1928 when Bonis was 70 years old.

A very prolific composer, particularly of songs, Bonis shared classes with Debussy at the Paris Conservatoire and produced work during an exciting creative period in Europe and, particularly, France.

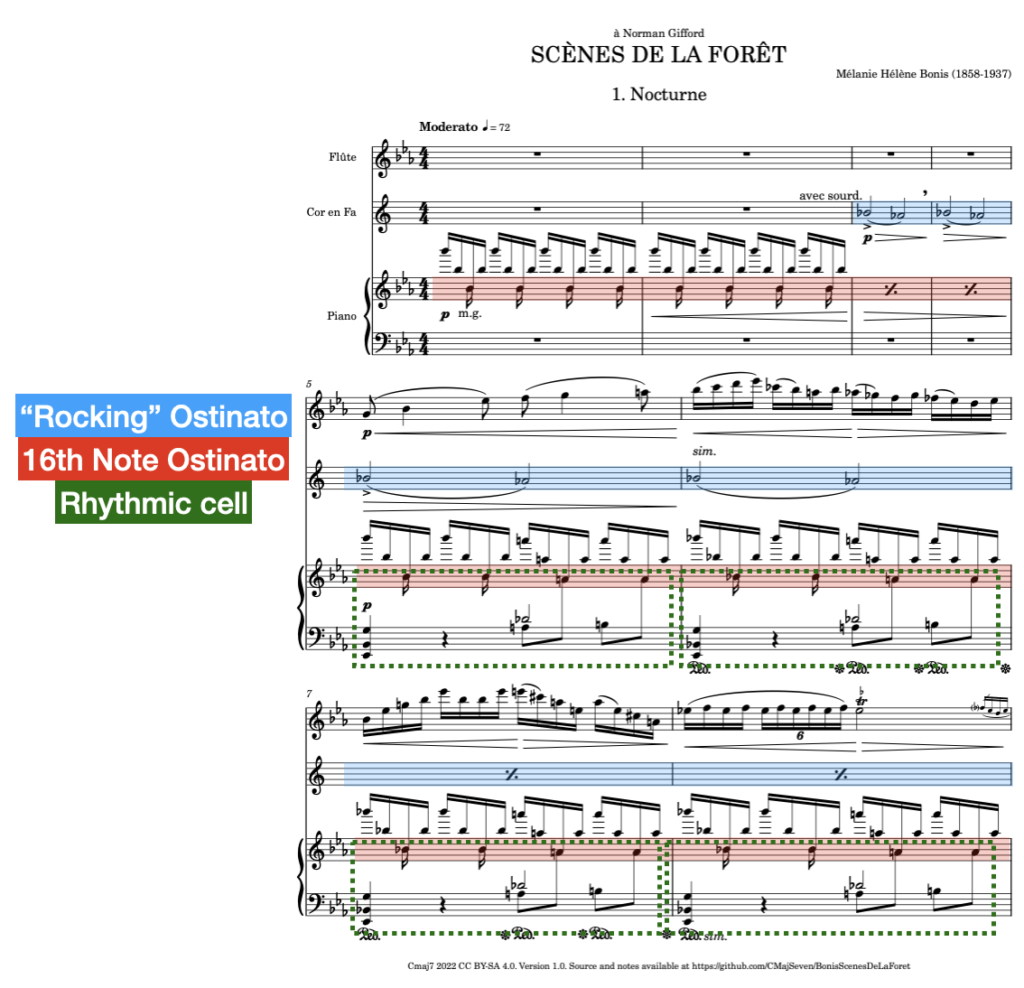

Scenes de la fôret is a suite of four movements, written for flute, French horn and piano. Nocturne is the first movement and the piece we will be analysing in this article. We will be looking at the form of the piece and its loosely ternary structure, the pieces use of melody––while looking at the form––Bonis’ use of repetition, which reveals a use of ostinati and a great deal of economy, and harmony, which pivots around the ostinati, juxtaposes harmonic colours and sonorities/chord structures.

Form & Melody

Bonis’ Nocturne, as I mentioned in the introduction, is in ternary form. Essentially meaning one can identify sections that follow an ABA schema. Largely speaking, in this instance, the form is built around a large-scale change of key in the middle section, to Db-major/Bb-minor. The outer A sections are in Eb-major, though all sections have modal-chromatic inflexions.

The ABA form is also supported by a reoccurrence of the opening four bar melody. While the closing A-section is truncated, using what could be described as the opening theme’s antecedent phrase, the opening A-section uses this theme twice while adding a consequent and additional four bar idea to the mix.

In some respects we could argue that the repetition of the opening melody, in the short final section, is more like a coda or codetta, and the structure is more Binary, on balance. It’s up for debate, but I would edge towards ternary as the repetition is a clear restatement and not a fragment or varied version.

Furthermore, regarding the piece being ternary form, the movement has an evocative title: Nocturne. Chopin, the quintessential nocturne creator along with John Field, almost exclusively used ternary structures for his his Nocturnes.

Different to A Chopin Nocturne?

That being said, drawing the comparison to a Chopin Nocturne, Bonis’ is very different. The melodies, for instance, are not bel canto and more idiomatic of flute. Moreover, as we will touch on, the chromaticism that Bonis uses is significantly different. For example, Chopin, who was an early-romantic, used chromaticism in a way that pulls against the underlying functional tonal harmony as if it were an anchor. Whereas, in this piece, the chromaticism is often used functionally, in a sense, to elucidate or embellish the underlying harmony. Bonis’s chromatic notes add washes of colour and thrust the harmonies upon us. Chopin’s pull and tug at the tonal anchorage.

If you are enjoying this article, then you should consider subscribing to Any Old Music’s emailing list, to be notified when we release new and mailing list exclusive content (e.g. One Page Summaries and Creative Briefs etc.).

An impromptu analysis of the comedic melodies John Williams created to underscore the devious, Gilderoy Lockhart, in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

Economy: repetition and ostinati

Mélanie Bonis uses a great deal of repetition in Scénes de la Fôret’s, Nocturne, which becomes immediately apparent when looking at CMaj7’s edition of the score and their use of repeat bar short hand markings. Moreover, one can also immediately see the repetition of a semiquaver figure in the right hand of the piano and a use of a rhythmic figure/cell that is used throughout the A-section of the composition.

Ostinato

The semiquaver figure and the rhythmic cell are themselves a form of ostinato. Particularly, the former. However, the main ostinato figure in this movement is a simple “rocking” idea presented by the muted French horn, between concert Eb and Db (Written: Bb and Ab). The “rocking” idea persists throughout each section of the piece, and the semiquaver figure typically takes on a form of counterpoint against the “rocking” ostinato, enriching the subtle motion between these parts and the underlying harmony.

The harmony, which we will go onto, tends to orient, or pivot, around the ostinato, enforcing an economy on Bonis that requires her to use different chord structures (e.g. augmented) to maintain a coherence between ostinato and harmony notes.

Delineating a string quartet and string orchestra in the instrumentation and engraving of Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Strings impacts its composition, orchestration and …

Harmony: juxtapositions of roots, structures and modal colours

Having established the sense of a “rocking” motion in the main ostinato idea, the orientation of the chords around that ostinato invites a further “rocking” or “swaying” motion in the harmonic language.

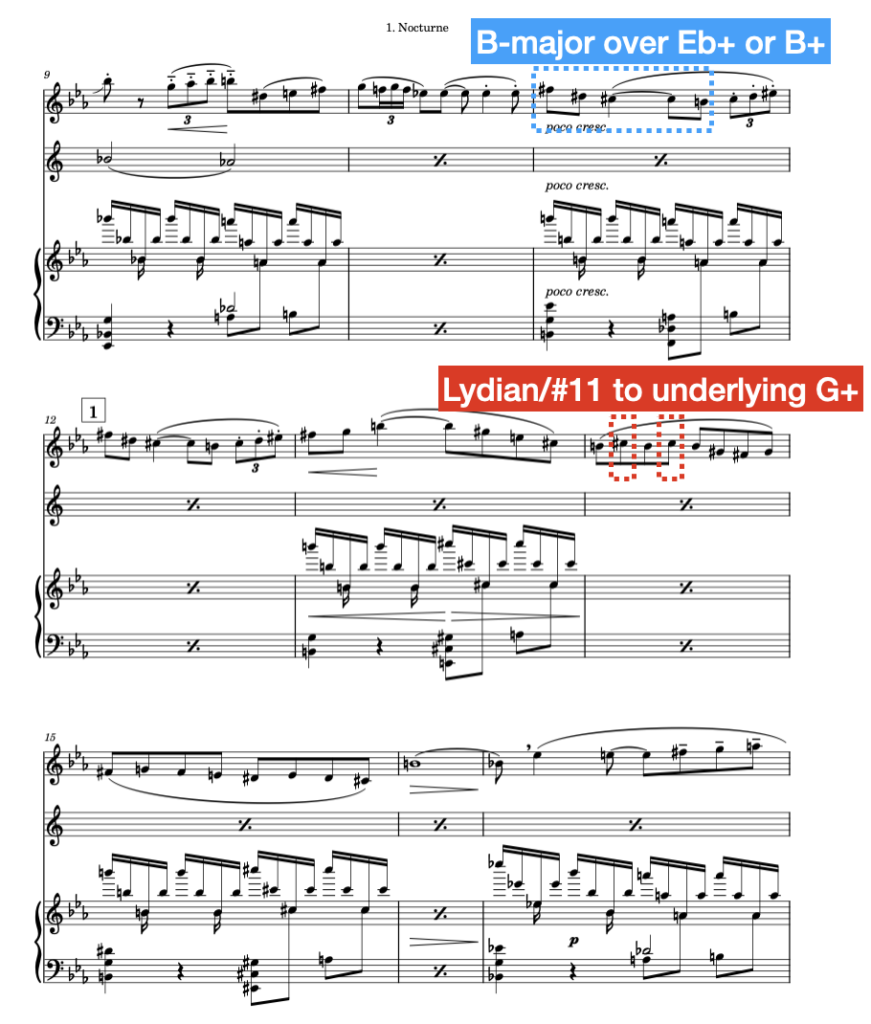

Bonis, building chords around the notes of the ostinato, oscillates between chords that have fundamentals/roots a #4 (or b5) apart. For example, in the very opening bar switches between an Eb and A+ chord. And, while the A+ often changes, the note A often remains in the bass position, rocking us back and forth between Eb and A. Moreover, from bar 13 – 16, Bonis switches between chords of G+ and C#-minor (bar 13 -14) or C#-major (bar 15-16). The G+ is rooted by B-natural, but I would argue, having had the “rocking” #4 root motion established so repetitiously in the beginning, we still feel that motion between the G+/B and C# chords.

Modal Inflexions

(I do not really do this section justice, or as clearly as I could in the video. I will attempt to do better here.)

As I mentioned in the earlier section regarding the difference between Bonis’ use of chromaticism to that of Chopin in one of his Nocturne’s, Bonis’ chromatic notes tend to elucidate the harmony. What I mean by this is, the melody––though certainly not always––takes up notes that complete or colour the harmony in some way or another. For example, in bar 14, the use of C#s over the G+, similarly to the larger chordal juxtaposition between G and C#, impose a #11 or lydian quality.

Similarly, in bar 11, Bonis juxtaposes a B-major passage against an Eb+, reorienting/pivoting the the augmented chord, that could also be seen and is rooted as B+, around the ostinato. In this instance, the melody helps affirm B-major, in some respects, while also demonstrating the parsimony of Eb and B harmonic structures.

Close

Not intending to be a comprehensive analysis of Mélanie Bonis’s Nocturne from Scénes de la Fôret, as I only came across the piece earlier this week, I hope to have provided some useful insights and compositional inspiration by revealing some of its inner-workings!

The Nocturne is a remarkable piece that accomplished what very few musical pieces do for me: inspire imagery. The music gave me the feeling of walking through a forest at night time. Dark, broodingly mystical, the branches and leaves of trees sway in the wind. The wind then glances off my face, chilling my cheeks. I can feel the wind; it’s remarkable. Even more so when one considers Bonis only needed a flute, French Horn and piano to give me such imaginings.

If you have enjoyed this article, then you should consider subscribing to Any Old Music’s emailing list, to be notified when we release new and mailing list exclusive content (e.g. One Page Summaries and Creative Briefs etc.).

Pingback: 5 Music Books I would Take into Exile - Any Old Music

Pingback: Salut D'amour - Edward Elgar (Music Composition Technique Analysis) - Any Old Music