A few months ago, I shared an analysis on the Hal Leonard arrangement of John Williams’ Flag Parade cue from the first Star Wars prequel, The Phantom Menace (1999). With these types of articles and videos, the objective is to unearth structure, concepts and techniques of composition via analysis. Occasionally, as I present today, I like to try and double down on those composition technique articles and videos by composing something based on the analysis. The aim of these pieces is not to create a pastiche of the original composer but to combine my inclinations with concepts and techniques discovered in the analysis article. Undertaking this process will, hopefully, provide two things: (1) a deeper understanding of the analysed piece and (2) an opportunity to develop our skills as composers.

In today’s article, I will be reflecting on my effort to compose an original composition that takes John Williams’s Flag Parade as its model. To do this as clearly as possible, I will compare the different sections of my work with Williams’s. Starting first with the main sections, I will compare the main themes of the pieces and the creative decisions I made. In the following sections, I will look at the smaller parts of the compositions, which were, surprisingly, more challenging to compose. Lastly, I will discuss, briefly, the tonal structure of the work and how I deviate from Williams’s piece. Below is a score video of my composition.

Composing the main sections

Theme A

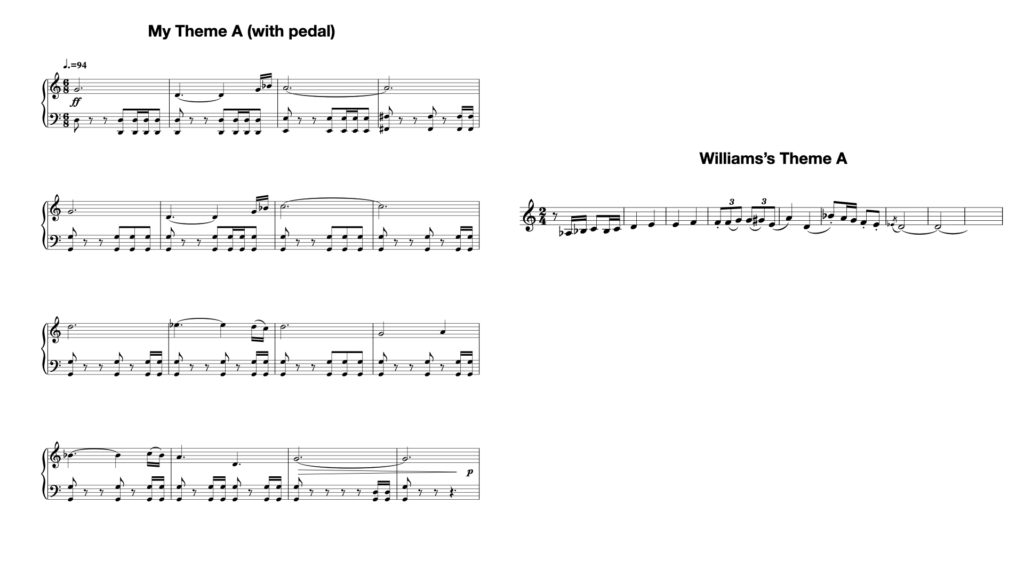

In terms of the arrangement, I paralleled the breakdown I created of Williams’ composition quite closely. For example, I use two core themes, one of which is used more extensively in different keys. This theme is called “Theme A” and is a melody I composed several years ago. I saw this composition lesson as an opportunity to purge the idea and get it out of my system!

Theme A is very much my melody and is in 6/8 rather than 2/4. It also does not undertake chromatic modal inflexions, like Williams’s. Instead, it is broader, featuring a compact series of motifs. The clearest similarities with Williams’s theme A is the textural setting and the orchestration. Williams uses a heavily doubled harmonic pedal underneath his melody. I do something similar using four horns, two clarinets and Violas on the melody, and two bassoons contrabassoon timpani piano divided cellos and double basses on the bass pedal.

For the repeat of theme A, which is a minor third upwards, I delay the movement of the harmonic pedal to the tonic note like Williams. However, due to where my harmony ends after the fanfare transition (that we will discuss shortly), I start my pedal on the dominant note, D, rather than the raised submediant, E. (These are D and F respectively for Williams’s Flag Parade, as his piece is a Major 2nd lower than mine. Something else we will discuss shortly.)

This week I was fortunate enough to stumble on a YouTube video by composer Zach Heyde. In this video he analyses the

An impromptu analysis of the comedic melodies John Williams created to underscore the devious, Gilderoy Lockhart, in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

Theme B

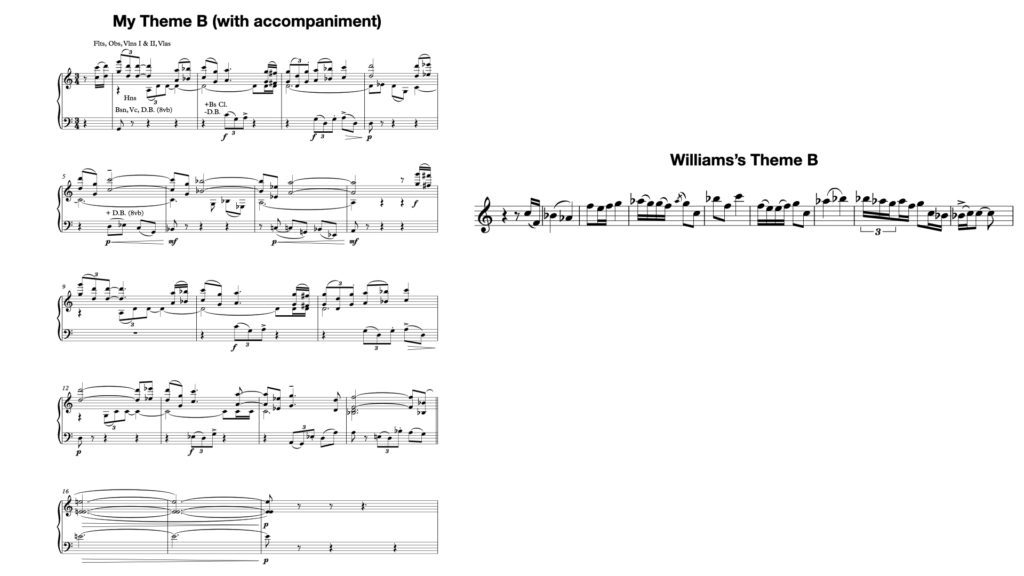

Theme B, composed specifically for this piece, counterpoints theme A. Just like how Williams creates a less rhythmically stable theme to juxtapose his theme A, I also orchestrate the idea top heavily and ensure smaller note durations fall on the stronger beats of the bar. I also switch the metre of my theme B from 6/8 to 3/4, altering the division of the bar. Due to all these things it contrasts Theme A greatly, in my opinion.

I still think this melody is very much my own. However, I do think, out of the two themes, it gets closest to Williams due to its rhythmic qualities. Furthermore, while Williams doesn’t do this in his composition, my decision to use imitative fragments of the melody as part of the bass accompaniment feels like something he would do. For example, he uses imitative––almost fugal––counterpoint in March of the Resistance from Star Wars VII: The Force Awakens.

As with all my analyses, they are not intended to be exhaustive and, thus, definitive. Therefore, there are some ambiguities regarding Williams’s Theme B specifically. For example, the exact tonal and harmonic procedures and how these link to the surrounding section are left uncovered by my analysis. However, I was content to leave those ambiguities in place when composing to try and leave space for my own creative solutions.

Embracing the ambiguity of my analysis of Williams’s Theme B, I decided that it would be economical to use the eight-bar consequent of my theme B. I felt this created a varied repetition on a larger scale that is not changed melodically but in duration and, as a result, shape. Rather than having to invent melodic developments, I felt this worked and was a quick and simple creative solution.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up for our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

The Punctuation Marks: Fanfares (1 & 2), Introductory section and Coda

In addition to the two themes that Williams’s Flag Parade boasts, there are two types of fanfare (1 & 2), a coda and an introductory section that appears twice, once at the beginning. And again, to transition into the final repetitions of theme A.

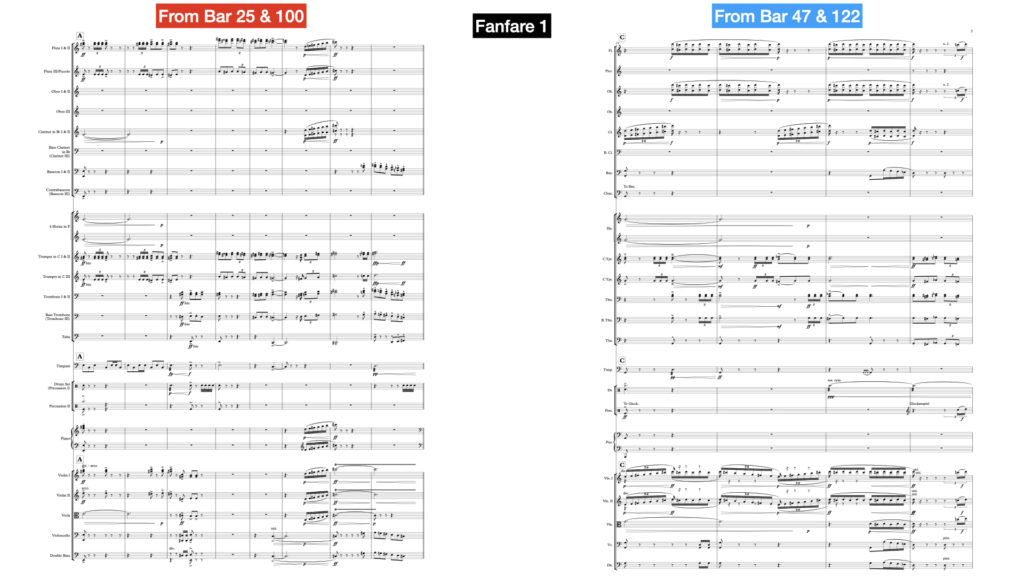

Fanfare 1: planing chords

My fanfare one sections are similar to Williams’s in that I use triple tongue planing figures. However, I also mix in other voicings and use greater chromaticism. For instance, Williams largely planes around the tonic chord of D major using bVII and bII chords. Whereas I, unbound by the presence of a film, afford myself some adventure. For example, in the first of the fanfare one sections, each chord changes as follows: Em – Cm – E – G# – E – G# – D4min7 – E – D# – E – D – C# – D – C – D – C – D – C# – C – D.

The progression I use is much more chromatic but also has qualities similar to Williams’s progression. For example, I also tonicise a chord by moving between tonic and forms of supertonic and leading note chords. Toward the end of the section, for instance, I use chords D (I), E(II), C(bVII), and C# (VII).

The other point of divergence, like with many sections of my piece, is the orchestration. I do this more empathically, without deeper analysis. In other words, I accept the limitations of my understanding of Williams’s piece to allow my own creative choices to take form. Therefore, unlike my London Bridge-Farandole arrangement, where I closely recast the orchestration, in this experiment, the orchestration was imitated from a distance and, sometimes, ignored altogether. Fanfare 1 is one of those sections, particularly in its E-major form. In the E-major sections, the orchestration is less frilly than my other fanfare 1 section, and Williams’s is fanfare 1 sections in general.

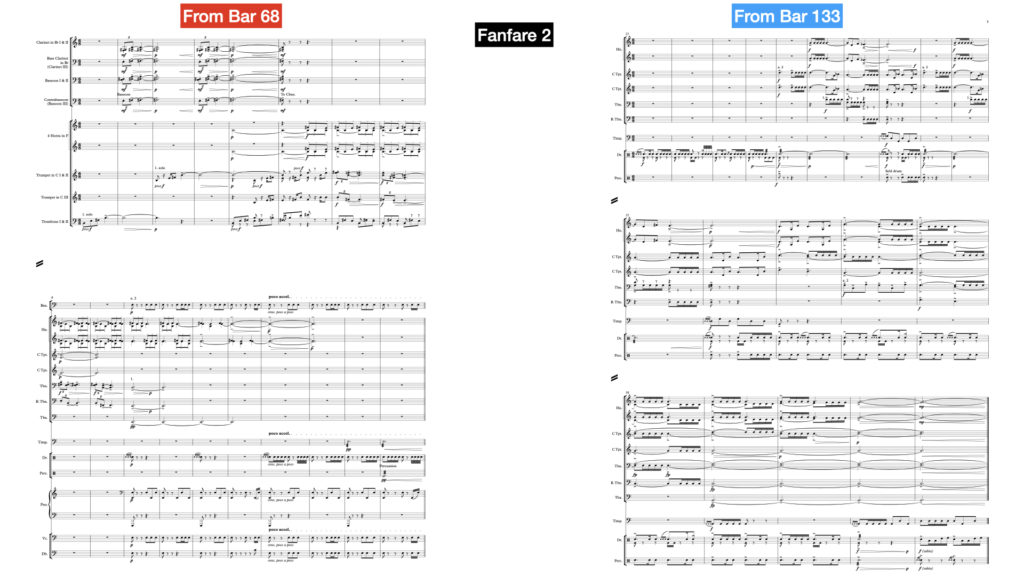

Fanfare 2/Transitions

The two fanfare 2 sections, which are different to each other, serve as transitions in my composition. Weirdly, they were the most challenging sections to write. I am unsure why, and I remain unconvinced with the quality of these sections even now. My guess is that I do not ordinarily think of transitions as a section but something that happens and is something I usually bake into the ending of an idea. Here, on the other hand, I was forced into doing something different, which was good, albeit challenging.

My first fanfare 2 is quite different to Williams’s in that it happens after theme B, whereas Williams’s fanfare emerges out of his theme B. In this way, I think this gives Williams’s first fanfare a feeling that things are occurring naturally, where the mine does not.

For the second fanfare two, both mine and Williams’s use drum rolls to abruptly transition into them. I feel like the shifts here, for Williams, are purely pragmatic, facilitating transitions within the confines of what the film would allow. Despite this, I followed suit, as I thought, again, that it would make me do something different structurally that I would not ordinarily have done.

How does John Williams create such compelling melodies? Let’s find out.

Chopin’s 20th Nocturne in C#-minor, published posthumously, is a brooding piano solo that boasts, unsurprisingly, facets quintessential to Chopin’s Nocturnes. These qualities,

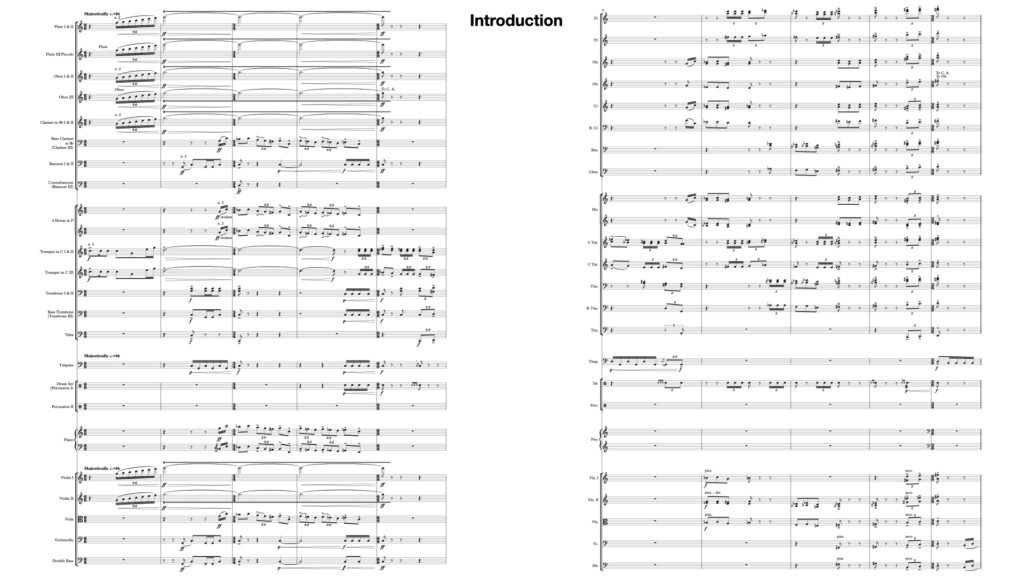

Introduction

Like with the second fanfare 2, the introduction, which appears twice, imitates Williams’s fanfares and introduction on a cursory level. Something I did deliberately, to avoid a straight copy, which is not what I wanted to do(!), I attempted to copy general orchestration gestures via simple observations of the score. I felt this allowed me the comfort of relying on the quality decisions made by John Williams while also coming up with ideas within that safety net.

Tonal Structure and Deliberate Deviations

For the tonal structure of my piece, I largely follow my analysis of John Williams’s Flag Parade. However, I opted to place my composition a major-2nd higher. I did this to ensure the repeat of Theme A would be in the key that I originally composed it: G-minor. Furthermore, starting in G minor and following Williams’s tonal progression would mean that orchestrations of the melody would either be very high or low in the ideal instruments (Horns or Trumpets).

My only deliberated deviation from Williams’s Flag Parade, beyond transposition, was to place the final repeat of theme A into the major, rather than minor, subdominant, A-major. I did this because I liked the effect that Guiraud created in his arrangement of Bizet’s Farandole. In modulating to the parallel major, it was uplifting and heroic in sonority, in my opinion. Therefore, I use major to try and create a similar feeling, which I think it does.

Close

The intent of this exercise was not to write a pastiche, nor was it to write something good. The aim was to practice composition, arranging and orchestration by copying aspects of Williams’s Flag Parade from Star Wars I: The Phantom Menace. Some parts of my piece work very well, providing me with things to reapply in future. For example, the overall structure balances the economy of writing and fresh material very well, in my opinion. Therefore, using this design again or adapting it could be a good approach for a future composition.

Other sections and things work less well, such as the smaller scale writing of my fanfare 2s, which could do with more work or revising completely. I also question the sudden A-major shift for my finale Theme A section. It might have been better to leave the modality to unfold gradually through the section as opposed to confirming it abruptly with a brass A-major chord. Then, I also like its sudden shift in a way too, so… yeah.

In their 1976 composition, Für Alina, for solo piano, Arvo Pärt introduced the world to his algorithmic technique, tintinnabuli. At first glance,

An impromptu analysis of the comedic melodies John Williams created to underscore the devious, Gilderoy Lockhart, in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition

Composed for the film The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), Bernard Herrmann’s science-fiction score has a lot to teach us about composition

Bernard Herrmann’s “Walking Distance” is full of different orchestration and composition techniques. Last week we focussed on some of those orchestration techniques, such

It’s easy, when composing for something like a string orchestra to simply think of it as 5-parts: the 1st Violins, 2nd Violins,