Delineating a string quartet and string orchestra in the instrumentation and engraving of Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Strings impacts its composition, orchestration and arrangement. The reason is that it imposes a compelling dichotomy between a string quartet (solo strings) and a string orchestra (sectional strings). Doing this allows and, undoubtedly, encourages Elgar’s exploration of the solo – section contrasts between these ensembles. We are going to take a look at those contrasts.

A couple of weeks ago, we looked at Vaughan Williams’s Dives and Lazarus. In this article and video, we investigated the blending of solo, divisi and sectional strings. Elgar uses similar effects in this piece. However, the structuring and distinction of the two ensembles that I outline above offer further ways and different methods into how we can write for strings.

There are three lessons that I want to present here, taken from what Elgar does in this piece. These are:

- Structural counterpointing/juxtaposition of musical sections between solo and section string timbres

- Colouristic and numeric accenting of musical passages

- String Quartet as a section within the String Orchestra

1. Structural Counterpointing: solo vs section

The first lesson that I want to discuss here is structural counterpointing between solo string instruments in the quartet and sectional strings in the string orchestra. In other words, as the piece unfolds, we will hear a section that uses solo strings, followed by a section for string orchestra, or vice versa. The value of this is that we can hear, with clarity, the distinctive qualities between solo and section strings as they are laid barely before us.

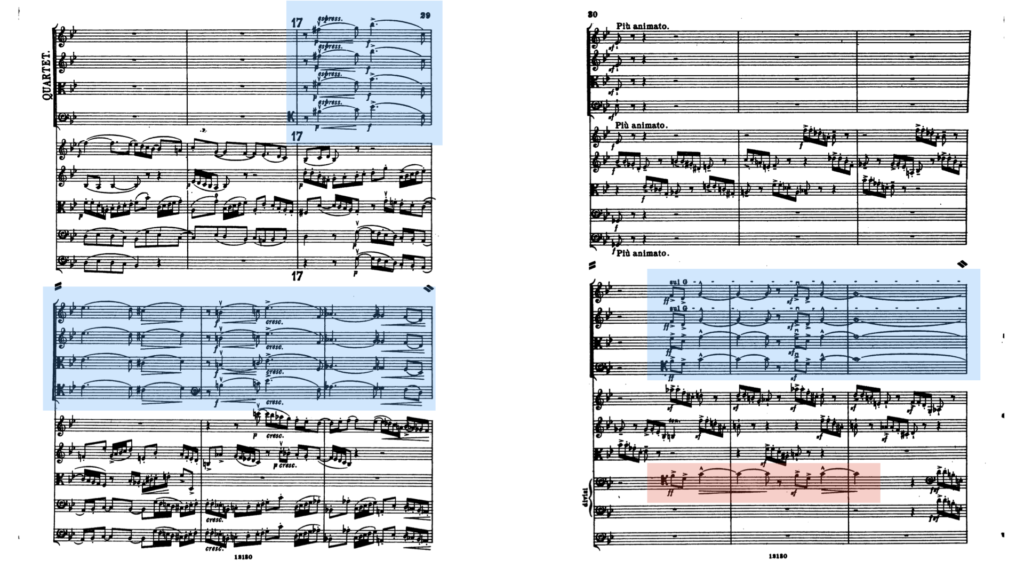

There are several examples within Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Strings, where one can see and hear this technique in action. The first, setting the tone of the piece, occurs close to the beginning, immediately after the emphatic Elgarian opening. At rehearsal mark 1, highlighted in the annotated examples below, we get a series of call and response interchanges between solo and string timbres. (We also get some divisi techniques and string blending similar to that which we identified in Vaughan Williams’ Dives and Lazarus, just before rehearsal mark 2.)

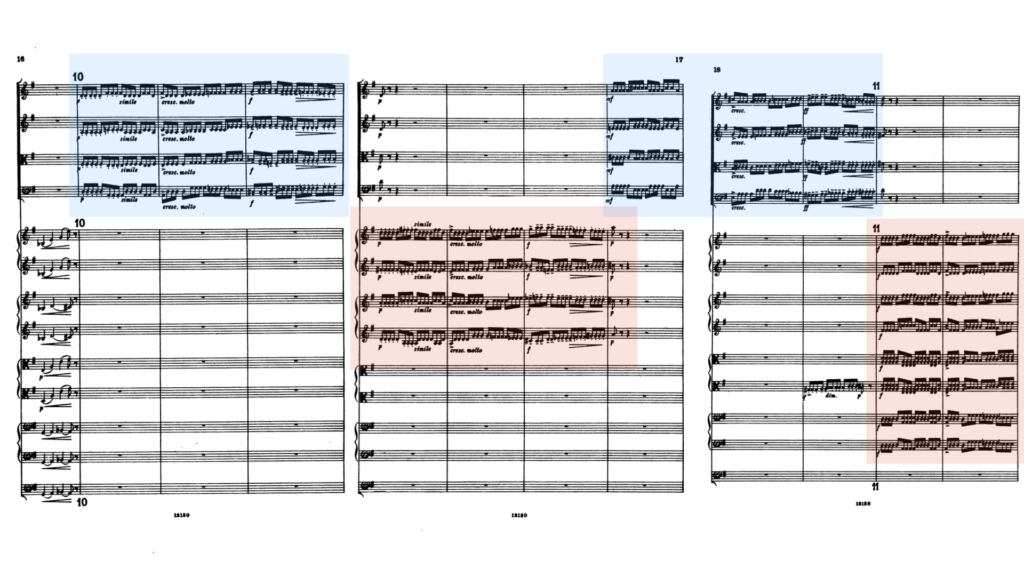

The same idea in ex.1 appears in a similar form throughout the piece. The motifs used in ex.1 being thematically significant. However, Elgar uses this same technique in different settings as well. For example, at rehearsal marking 10 (ex.2), Elgar juxtaposes solo and section strings using a quicker, measured tremolo figure. I particularly liked this brief section as it laid bare the timbral differences between solo and section strings.

Concepts of Orchestration: Presence and Weight

The distinction between these two timbres (solo and section) lies in what contemporary composer Rodney Sharman defines as “presence” and “weight”. In a fascinating 7-minute discussion (linked below) on orchestration, Sharman discusses how orchestration has a 3-dimensionality that is not only based on spatial-physical positioning (although this does have an impact) but acoustic aspects relating to instrumental/voice numbers, dynamics, effects and register. In other words, depending on instrumentation and orchestration, the presence or weight of particular notes can vary. Moreover, it is these things that allow us to play with this dimensionality as orchestrators.

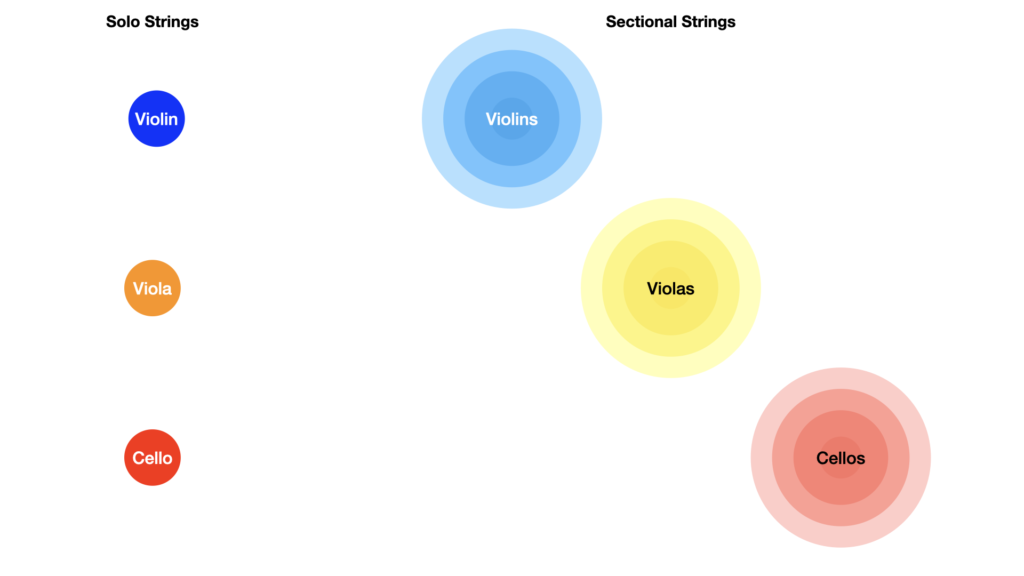

In Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro for Strings, the colouristic contrast between phrases is a numerical weight that leads to a difference in presence. I attempt to visualise this in the example below (ex.3). With solid, incisive colours, the three solo instruments stand out. They are distinguished via the intensity of their sharper colours. In contrast, sectional strings have a different presence. Less strident in colour, their presence is delivered via their weight in numbers. Their colour is hued but given mass.

Elgar, experimenting with this, juxtaposes incisive single voiced lines with the weight of many. The result is an altered presence. While the sectional strings rumble steadily through the hall, one feels as though they are more distant but that their momentum would be harder to stop. On the other hand, the solo strings have the speed and agility acting alone affords. Therefore, like a crack of lightning, they cut through the air with urgency and precision. (Maybe a little dramatic, but illustrates the point!)

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

This week I was fortunate enough to stumble on a YouTube video by composer Zach Heyde. In this video he analyses the

2. Numerical Accentuation and dovetailing

This technique, numerical accentuation and dovetailing, is similar to that of solo-section blending in RVW’s Dives and Lazarus. However, the way that Elgar deploys it here can expand our understanding and application of it. This is because Elgar uses the technique differently and in a more fragmented manner.

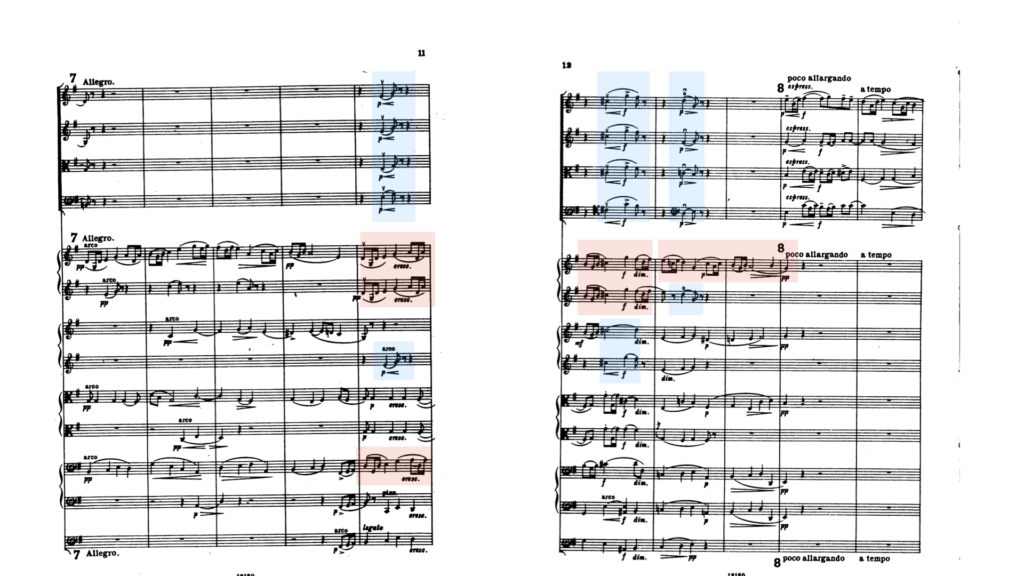

The technique, in Introduction and Allegro for Strings, centres around the string quartet. However, Elgar also frequently pairs this ensemble with a section or divisi section. Elgar makes use of the technique in two ways. One of these is to accent or counterpoint a line, while the other is to tether two phrases (dovetail).

Both of the techniques, however, colour melodic or accompaniment lines by altering their weight and presence. For example, if we take the below example (ex.4), Elgar uses the effect to dovetail the melodic line. Note how the melodic line in the 1st violins becomes a full section in the final bar of page 11, doubled by divisi celli. An altered repetition of the previous four bars, Elgar adds weight to the line and presence via the octave. The weight of the accompaniment is also increased. However, in further contrast to the previous four bars, Elgar uses the string quartet and divisi Violins, first the 2nds and then the 1sts, to dovetail the phrasing. Given additional dynamic and articulation markings, they not only smooth the phrases, but they do so by adding subtle shifts of weight and colour.

How does this affect the colour/timbre?

This form of doubling affects colour in multiple ways, including presence and weight. The numeric addition and momentary subtraction (between phrases) on these particular notes will cause shifts in perceived depth. (This perceived depth could also be affected acoustically by the layout of the ensemble(s).) As we have discussed, solo instruments carry less weight but have a forwarded presence due to their incision. Like a knife or rolling pin, the knife (solo-instrument) cuts, and the rolling pin (section of instruments) squashes.

Therefore, in the example above (ex.4), we have a pair of shifts between weight and presence. At the moments of dovetailing the 1st violins and cellos, the weight increases. However, there will be a moment of sheen between the phrases as the sections break and the string quartet and divisi 2nd violins continue sounding.

As Rodney Sharman discusses in the video on writing for orchestra, we can play with space in a 3-dimensional sense, and this is what happens here. Not only is there a numerical accenting, via increased weight, but a forwarding of the sound through increased presence. The orchestration steps forward and then back, forward and then back again.

In addition to this, the colour is also affected by the blending of different solo instruments. Similar to what we observed within the Dives article (see “3. Solo-section doubling” and “4. Divisi-section doubling”), the timbre will be altered momentarily by other string instruments. Here the viola and cello (particularly once the divisi cellos take up a different line), doubling 8vb, subtly reshape the timbre.

Overlooked in orchestration and instrumentation manuals, in my opinion, are dynamic levels. In one sense, I understand the reasoning for this: restricting the use of dynamics in learning about orchestration means one has to focus, as a student, on other means of finding balance and controlling the fore, middle and backgrounds of a texture. However, ignoring these leaves out a lot of opportunity for effect. Dynamics and articulations impact timbre and, thus, colour and shape a musical line. (Articulations are more readily spoken about in orchestration manuals. At least the ones I have read!)

To an extent, Elgar invites timbral change via dynamics in this example by having slight differences between the string quartet and section dynamic markings. (However, I wonder if this was a consideration of balancing as opposed to effect…?) He instructs the solo instruments to play slightly louder: piano as opposed to pianissimo. Furthermore, Elgar asks them to perform crescendi and articulate notes with accents and different bowings. While I cannot explore this here, the different dynamic levels and articulations will add shades of colour that make this line more interesting from an orchestration standpoint.

Teresa Amabile’s book, Creativity in Context (there are no affiliate links in this article), is one of the very few texts that I

3. String Quartet as a section

The last example of string writing in this article is a direct result of the ensemble. Broken into a string quartet and string orchestra, this example pits the two against one another. However, in contrast to the first example, which involved juxtaposition, this one exhibits superimposition. Superimposition, at least my use of it here, is where the two ensembles are pitted against one another simultaneously. (Juxtaposition, if you recall, is successive counterpointing of the ensembles. So, if we had a phrase of the string quartet, the next one might counterpoint this by having the string orchestra play.)

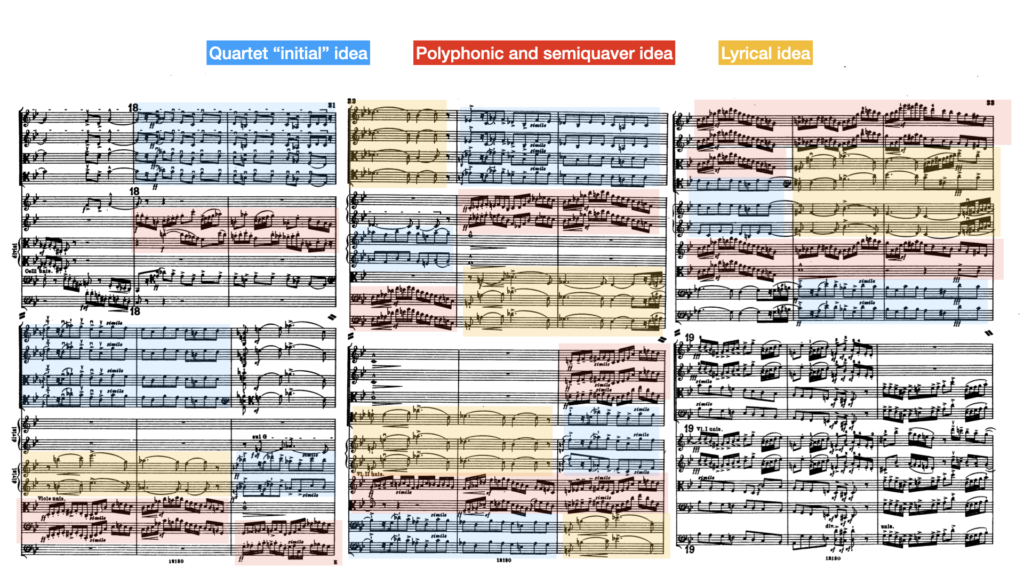

In this instance, the string quartet plays a melody in octave-unison and the string orchestra providing an accompaniment texture. Already an intense passage within the work, the accompaniment is polyphonic. The section, five bars before rehearsal mark 16, presents an 8-bar canon that morphs into a fugal, imitative texture. An energetic subject with several distinctive motifs, we get fragments of ideas that wrestle for our attention. This polyphonic texture is sustained as the accompaniment, as the string quartet comes in with a legato, expressive melody at rehearsal mark 17.

The orchestration creates the tension of this section. It is delicately balanced. Both string ensembles, their sounds are homogenous, the orchestra could engulf the quartet if it wanted to. Even with the material being distinct: the melody counterpointing the accompaniment in character. If the string orchestra was to increase in volume too much or change its material to be more similar then the quartet would stand little chance of being heard. This is where the tension lies, in this delicate balance.

Following this passage, the orchestration becomes even more complex as the ensembles’ roles become more stratified. At rehearsal mark 18, the string quartet takes up a doubling at the unison. Creating a distinct timbre made up of 2 violins, viola and cello, the quartet counterpoints the ongoing polyphonic texture and fragments of the lyrical melody.

The roles shift and cycle between sections of the whole ensemble. For example, at rehearsal mark 18, while the quartet is in unison, the string sections of the orchestra are divided. The second violins play the polyphonic texture in counterpoint with a portion of the violas, and a portion of the cello section doubles the quartet. However, this changes two bars later. The quartet continues, but the second violins take up the lyrical melody while the violas and cellos take up a semiquaver figure, a liquidation of the polyphonic texture. Another shift occurs two bars later. The quartet takes up the lyrical melody in octaves, supported by a portion of the 1st violins. The second violins play what the quartet has just played; the semiquaver figure moves to the cellos and double basses. After this, the violas, cellos and basses take up the lyrical melody; the quartet take up their initial idea, and the first violins get the semiquaver figure.

The cycling of these ideas continues between parts and combinations of the ensemble. The dance-like play with space that Rodney Sharman highlights is played out here in Introduction and Allegro for Strings. Varying levels of weight and presence give the ideas colour, planes of attention that creates variety between these cellular ideas that would be more difficult to pull off if thinking about the string orchestra as sections alone.

Summary

Just as with Dives and Lazarus, I would recommend taking a listen and look at this piece. There is certainly more to be taken from it than I present here. For example, Elgar briefly, but really cooly, uses con sordino and sul ponticello (playing with mutes and on the bridge to create a glassy sound) in this piece to reimagine one of the reoccurring melodies that often prepares the return of an allegro passage. (You should be able to hear it here. It makes the cello pizzicato a harp-like quality IMHO.) Furthermore, the use of the techniques I discuss is so frequent there is plenty more nuance to be unearthed.

The other thing is to try and get these techniques into your works. The overriding strategy that could encourage this is to set up your score or Digital Audio Workstation with separated solo, divisi and section strings. Doing so reduces the resistance to trying ideas out in different combinations. Give the solo strings a unison feature within your larger orchestrations! Test it out!

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …

![Remember that orchestration is not just a question of colour but, in the orchestra imparticular, it is a question of presence and weight. Perhaps the best examples of this in music are violin concerti. The solo violin always sounds closer to us and more present than the body of strings, and if they have mutes on[, sounding more distant,] and if they play harmonics [more distant, again] and we can go back and forth with these in what sounds to us like a three-dimensional sound space.](https://anyoldmusic.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Rodney-Sharman-Quote-1024x1024.png)