First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves writing one note of counterpoint for each note in the cantus firmus (fixed melody). By mastering first species counterpoint, students build a solid understanding of melodic and harmonic principles that are essential for more advanced counterpoint studies.

Sources (Counterpoint Books)

This article is a culmination of my study and use of 2-part counterpoint as a composer. While preparing my course 30 Days of Counterpoint, I have focused on two primary books. The first, a recent discovery, is “The Rules of Counterpoint: Systematically Arranged for the Use of Young Students” by William Smyth Rockstro. The second is my all-time favorite book on counterpoint, Owen Swindale’s “Polyphonic Composition.”

Interestingly, I discovered Rockstro’s text through a negative critique in “Contrapuntal Technique in the 16th Century” by Reginald Owen Morris. In this book, Morris criticises the rigidity of Rockstro’s and other species counterpoint teachings. I sympathise with Morris’s views, as I believe that learning counterpoint through the species method requires a period of assimilation into your personal fabric as a composer. However, I also think that learning systematically through the species method is a good way to achieve this assimilation. It allows you to consciously and unconsciously decide which concepts are universally (or at least more ubiquitously) important and which are aesthetically important or unimportant to you.

Below is a list of counterpoint books that I like, including some that I have used less thoroughly but have dipped into. All of these books are available online, many for free in digital format. I also provide links to digital and print versions of these books, with the print books including affiliate Amazon links:

- “The Rules of Counterpoint: Systematically Arranged for the Use of Young Students” by William Smyth Rockstro

- “Polyphonic Composition” by Owen Swindale

- “Contrapuntal Technique in the 16th Century” by Reginald Owen Morris

- Amazon US

- Amazon UK

- Internet Archive [Recommended over Amazon options]

- “The Study of Fugue / Gradus ad Parnassum” by Joseph Fux / Alfred Mann

- “The Study of Fugue” by Alfred Mann

- “Elementary Counterpoint” by Percy Goetshius

Historical Context

Counterpoint has its roots in the monophonic music of the early mediaeval period, where a single melodic line dominated. From the 10th century onwards, composers began experimenting with combining two or more lines. Experimenting with multiple lines that grew in complexity and independence led to the development of polyphonic composition, with notable contributors like Machaut, Dunstable, Dufay, Ockeghem, and Josquin des Prez. By the 16th century, polyphony reached a high level of technical perfection, as exemplified by composers like Lasso, Victoria, and Palestrina. Their consistent and refined use of polyphonic techniques allows us to formulate precise rules for counterpoint, which we begin to use here in their most constrained form: the 1st species. In subsequent articles, we will discuss 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th species counterpoint.

Fundamental Rules of First Species Counterpoint

First species counterpoint is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It involves writing one note of counterpoint against each note of a given cantus firmus, adhering strictly to consonant intervals and focusing on melodic smoothness and harmonic clarity. Mastering first species counterpoint builds a solid understanding of the fundamental principles of counterpoint, which is essential for progressing to more complex contrapuntal writing.

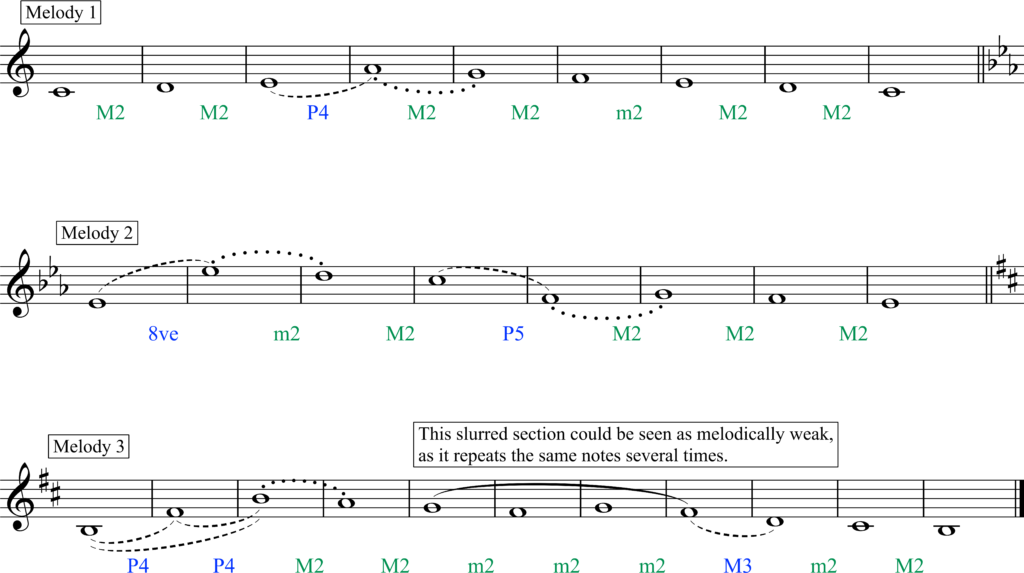

1. Melody

The melody in first species counterpoint should be smooth, stepwise motion with carefully controlled leaps. A focus on conjunct (smooth) melodic writing ensures a coherent and singable line that complements the cantus firmus.

- Stepwise Motion: The melody should primarily move stepwise (by seconds). Octave leaps are permitted, but major and minor sevenths and major sixths are not allowed. Minor sixths can be used as upward leaps. Augmented and diminished intervals, including the tritone, are strictly forbidden.

- Leap Compensation: Any leap should ideally be followed by a step in the opposite direction. Two leaps in the same direction are allowed if they do not add up to a major seventh or exceed an octave.

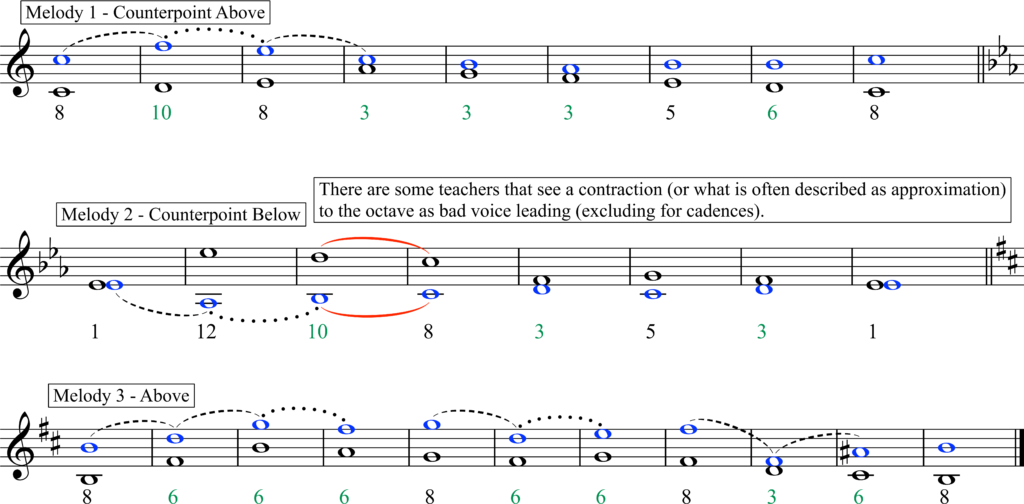

2. Harmony

Harmony in first species counterpoint relies on the use of consonant intervals to create a pleasing and stable sound. The careful selection of intervals helps maintain the independence of the melodic lines while ensuring harmonic coherence.

- Consonant Intervals: Use only consonant intervals between the counterpoint and the cantus firmus. These include:

- Unison (Only allowed on first and last note)

- Octave

- Perfect fifths / twelfths (compound perfect 5th)

- Major and minor thirds / 10ths (compound major / minor 10ths)

- Major and minor sixths

- Avoid Dissonances: Be cautious with the intervals of the fourth and diminished fifth. Although they may appear consonant in isolation, they can create discord in context.

- Emphasise (but don’t overuse) imperfect consonances: In the middle (all notes but first and last note: see next point) of your counterpoint use richer imperfect consonances such as the 3rd and 6th.

- First and Last Notes: The first note of the counterpoint must form a perfect consonance with the first note of the cantus firmus. The final note should typically form an octave or unison with the cantus firmus, providing a sense of closure.

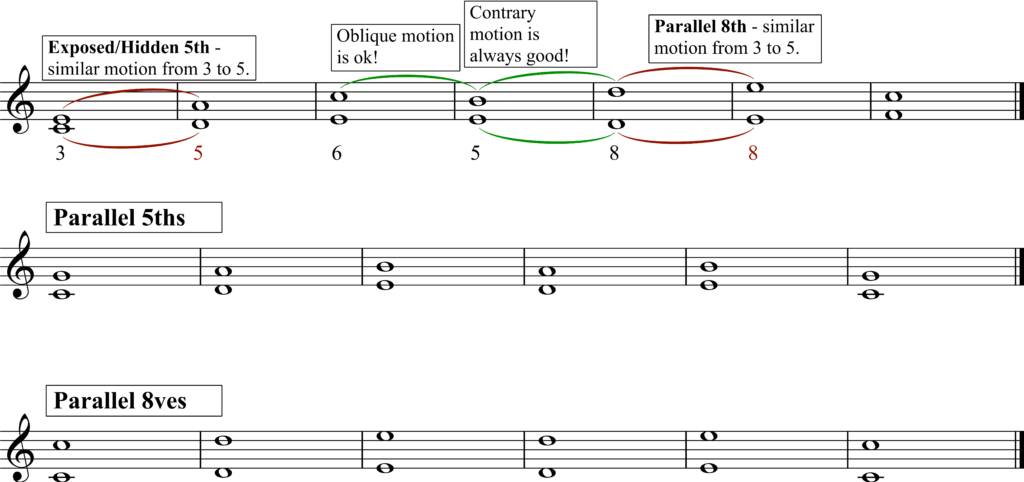

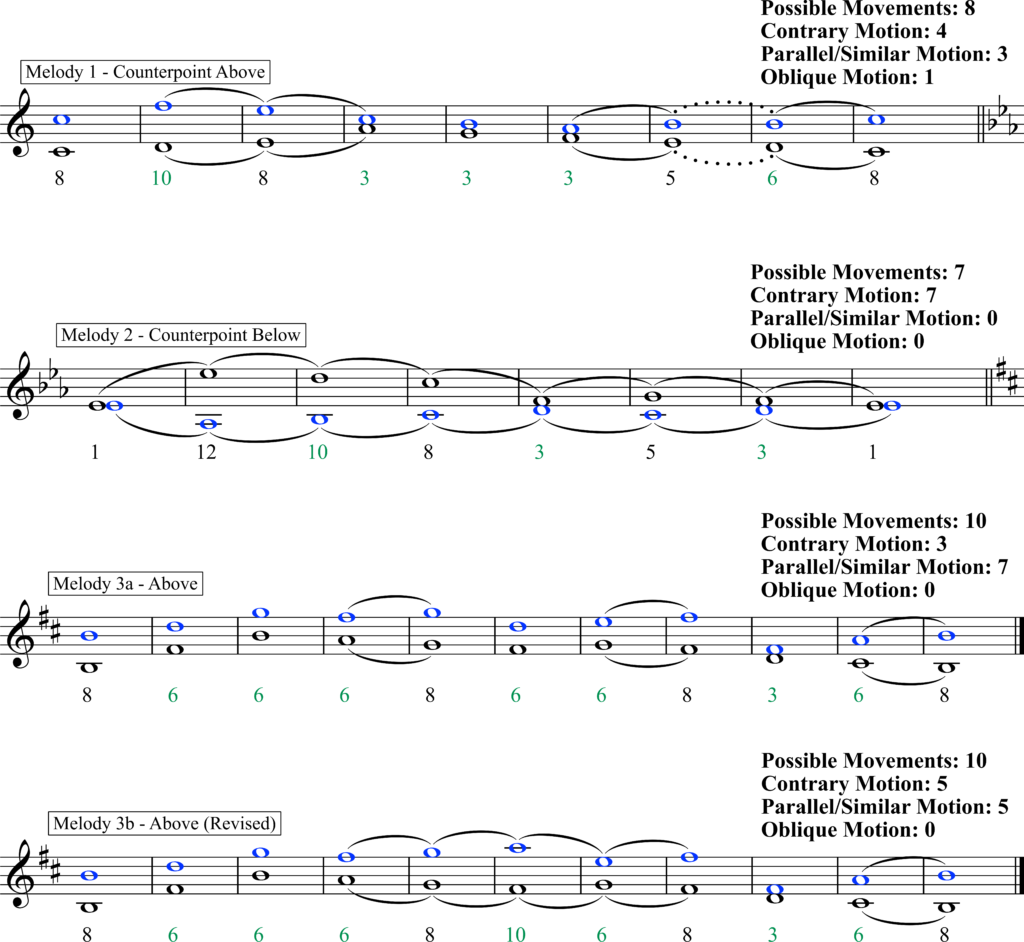

3. Voice Leading

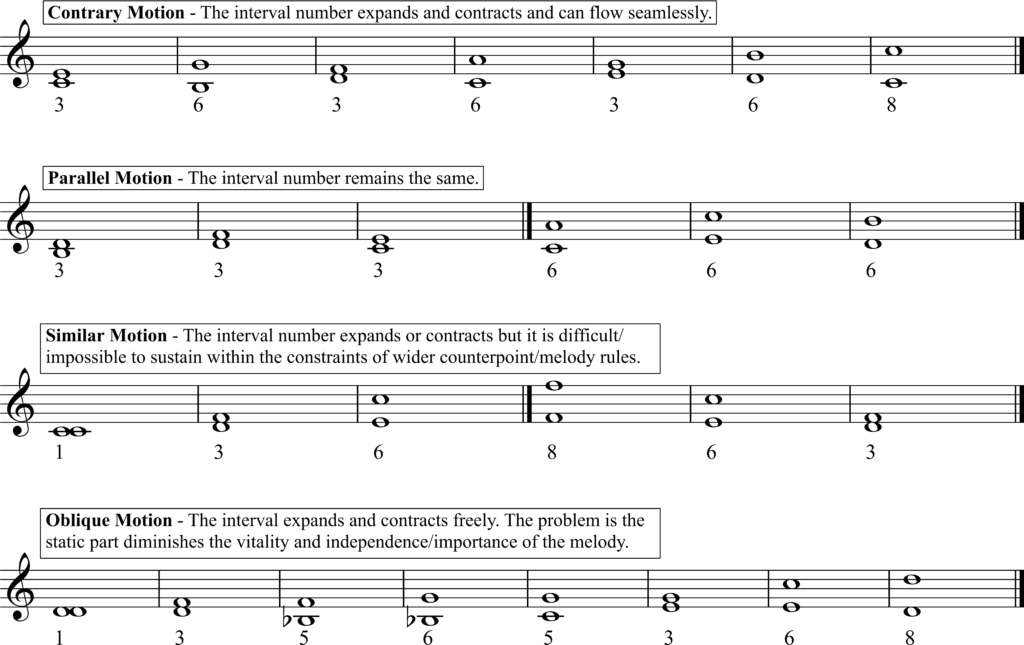

Effective voice leading ensures that the individual melodic lines move smoothly, harmoniously and independently. By prioritising contrary motion and avoiding parallel intervals, composers can create counterpoint that is both clear and expressive.

- Contrary Motion: Focus on contrary motion (one part moves up while the other moves down) as it provides the greatest independence and clarity between the parts.

- Parallel Movements: Parallel fifths and octaves are forbidden as they undermine the independence of the parts. Also, do not overuse parallel 3rds and 6ths. As a guide, use no more than 3 parallel 3rds or 6ths in a before breaking up with different motion and intervals.

- Oblique Motion: Incorporate oblique motion (one part stays the same while the other moves) sparingly to add variety and maintain independence between the parts. However, as it diminishes the vitality of a melody through stasis and note repetition, I would limit its use to once per counterpoint (possibly two if its a longer cantus firmus).

- Avoid Exposed Fifths and Octaves: Ensure that both parts do not move in the same direction to an octave or a fifth, as this creates a sense of ‘exposure’ or predictability.

- True Cadence: Ending with an octave must be approached by contrary motion. Typically, a cantus firmus will approach the final tonic note by a descending step from above, or less frequently, by rising a step from below. Therefore, if the cantus firmus descends a step, you must approach the tonic by a rising step from the leading tone. Conversely, if the cantus firmus rises a step from below the tonic, you must approach the tonic by falling a step from the supertonic above the tonic.

4. Rhythmic Considerations

- Semibreves and Breves: Use semibreves (whole notes) for the bulk of your first species counterpoint. Breves (double whole notes) are best placed at points of cadence at the end of phrases to maintain rhythmic flow.

- Lively Tempo: Despite the appearance of ‘white’ notation (minims and semibreves), the tempo should be lively, reflecting the fast-moving nature of 16th-century music.

Practical Recommendations

- Interval Awareness: Be aware of every interval you write; it can help to number each interval to keep track.

- Hear the Lines: Ensure you can hear both lines separately and together. This aids in understanding their interaction and independence.

- Implied Harmony: Focus on smoothness and independence of parts over strong chord progressions. Understand what chords might be implied if a third part were added.

- Consider my course 30 Days of Counterpoint: Introducing a handful of concepts and rules each day, via short video lessons I provide structured and progressive worksheets that provide counterpoint exercises for your to develop your counterpoint skills. Designed for beginners to counterpoint it is intended for intermediate students too, who might have dipped in and out of texts and courses aiming to provide that shot in the arm to get you counterpointing within a month!

Conclusion

Writing first species counterpoint involves a delicate balance of melodic movement, harmonic consonance, and rhythmic integrity. By adhering to the rules and guidelines outlined above, composers and students can create music that is both technically sound and aesthetically pleasing. Mastery of first species counterpoint lays the groundwork for more complex contrapuntal techniques, making it an essential skill for any serious student of composition.

Pingback: How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide - Any Old Music

Pingback: How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide - Any Old Music