Video watchers look up, Readers scroll down!

In this article, I want to investigate the compositional technique used in Arvo Pärt’s Für Alina. One of the earliest works to use his trademark style of Tintinnabuli, I think Für Alina is a fantastic study in this style of composition. Therefore, it is a great starting point to explore and learn the techniques of Tintinnabuli and Arvo Pärt.

In analysing Für Alina and discussing Tintinnabuli, we will about restricted creativity and how we can source inspiration from musical and sonic influences. For example, the origins of Tintinnabuli lie in a mixture of medieval organum and the overtone series of bells. These influences, each impose restrictions on texture and harmony/tonality.

The article, therefore, will discuss the following:

- Tintinnabuli and its origins in the overtone series of bells

- Tintinnabuli and organum

- Rules of counterpoint in Für Alina

- Symmetry of structure via phrase lengths.

Interested In Learning How To Compose Tintinnabuli? If so, I am currently offering the first chapter of my new tintinnabuli composition course for free here.

Tintinnabuli, bells and their relationship with Für Alina

Tintinnabuli, as a compositional technique, in part, originates from the overtone series of harmonically tuned bells. Tintinnabulum, from which Tintinnabuli derives, roughly translates from medieval Latin into “little bell”. Looking at the overtone structure of a European “well-tuned” church bell, therefore, seems a good starting point. This is because we can then draw broader parallels with Für Alina.

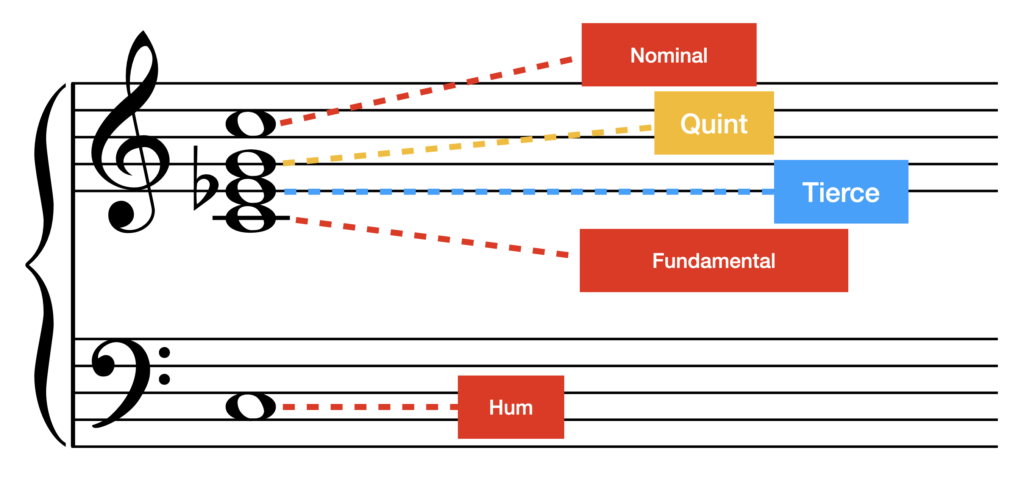

Below, I present a figure from a dissertation on Pärt’s tintinnabuli music, which I would recommend searching for if you would like to know more after reading this article. As we can see, in this image, there are several tones. However, the most important of these, excluding the fundamental tone, are the “hum” tone, tierce, quint and nominal. This is because these overtones are the most prominent and give a bell its distinctive timbre and sound.

Another great resource that discusses Bells and their acoustic properties in detail is the “Bell” entry on Grove Music Online. I was able to access the article without a subscription.

What is so special about the overtone series of bells?

We perceive the timbre of instruments through how they produce their fundamental note and emphasize upper harmonics. The relationship between those two things is vital as well. For instance, when playing an instrument, the pitch we hear is the fundamental note. However, within this note, instruments tend to produce other, less audible pitches. These less audible pitches are known as harmonics or overtones. The subtle variance of audibility between each of these harmonics is what gives an instrument its distinctive sound.

(Side note.) Timbral information is abundant in the attack (or transience) of musical instruments. This is because the accent of a note stresses and extends the overtone series momentarily. It also does it in a way that is unique to that instrument. For this reason, the amount of nuanced information within that split second increases. Therefore, if you remove or alter the attack of an instrument, so too is its timbre. As a result, the perception of a sound is, becomes harder. Sounds Good has done a video on this and timbre more widely.

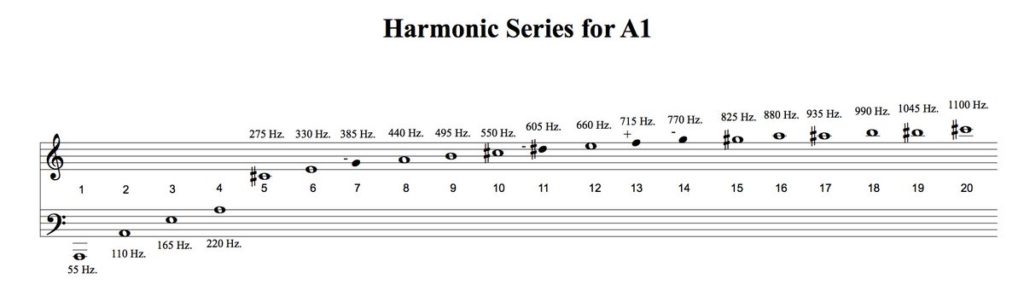

Harmonics and overtones produced by instruments tend to be restricted to the harmonic/overtone series. However, in the case of the bell, its structure is very different. Where the first few partials of the harmonic series are the octave, Perfect-5th and Perfect-4th; the bell emphasises the minor-3rd (tierce), perfect-5th (quint) and nominal (octave). (Compare Ex. 1 & 2.) Furthermore, the bell produces a hum tone, an octave below the “strike tone”. The “strike tone” is the fundamental pitch we hear at the attack of a bell’s note.

What’s so significant about a bell’s overtone series in relation to Tintinnabuli and Für Alina?

The unique overtone structure of bells is crucial to tintinnabuli and Für Alina through their emphasis on the root and minor-3rd relationship. In the bell, as we have seen, this comes in the form of the tierce. The tierce is a minor-3rd relationship between the fundamental tone and the 1st harmonic.

Tintinnabuli is a style known for its solemnity, which frequently uses minor modes. Furthermore, the technique involves a relationship between two voice types. One voice type is free to use pitches of the diatonic scale (m-voice) or mode; the other voice typically uses only notes of the triad (t-voice). Usually, that triad is the root triad of the key, which is frequently minor.

Für Alina, a composition that deploys the tintinnabuli technique, is in B-minor throughout. The minor-3rd and root relationship is the core characteristic of defining a mode or triad as minor. Moreover, the composition uses two parts, the m-voice and the t-voice. The t-voice only uses notes of a B-minor triad. (I discuss this more in the “compositional technique: tintinnabuli & Fur Alina section.)

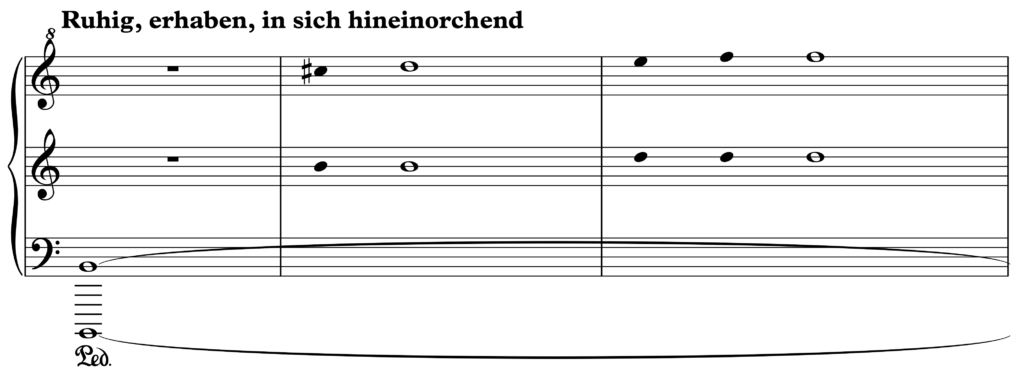

Additionally, in Für Alina specifically, Pärt further emphasises the relationship with the overtone series of bells by opening the piece with a low double octave (Ex.3). The effect of this reflects the “strike” – “hum” undertone effect distinctive of bells. The “hum” tone is a pitch that gradually resonates underneath the tone of the bell. Moreover, the decision to engrave the pedal tone on a third staff below the piano’s left hand is reflective of church organ music and its use of a pedal staff.

Interested In Learning How To Compose Tintinnabuli? If so, I am currently offering the first chapter of my new tintinnabuli composition course for free here.

In this article I discuss concepts in Margaret Boden's book Creativity and Art. Pulling out three points from her book, I discuss why I found them significant as a composer/creative practitioner.

Tintinnabuli, Für Alina, Organum and Plainchant

The use of the phrase tintinnabuli itself holds greater significance to the style of Für Alina‘s composition. As I have said, it is a medieval Latin term. While neither pastiche nor an artistic revisiting similar to neo-classicism. The technique evokes the sound of medieval sacred music such as organum and plainchant, while being more codified and prescriptive (at least in its use in Für Alina).

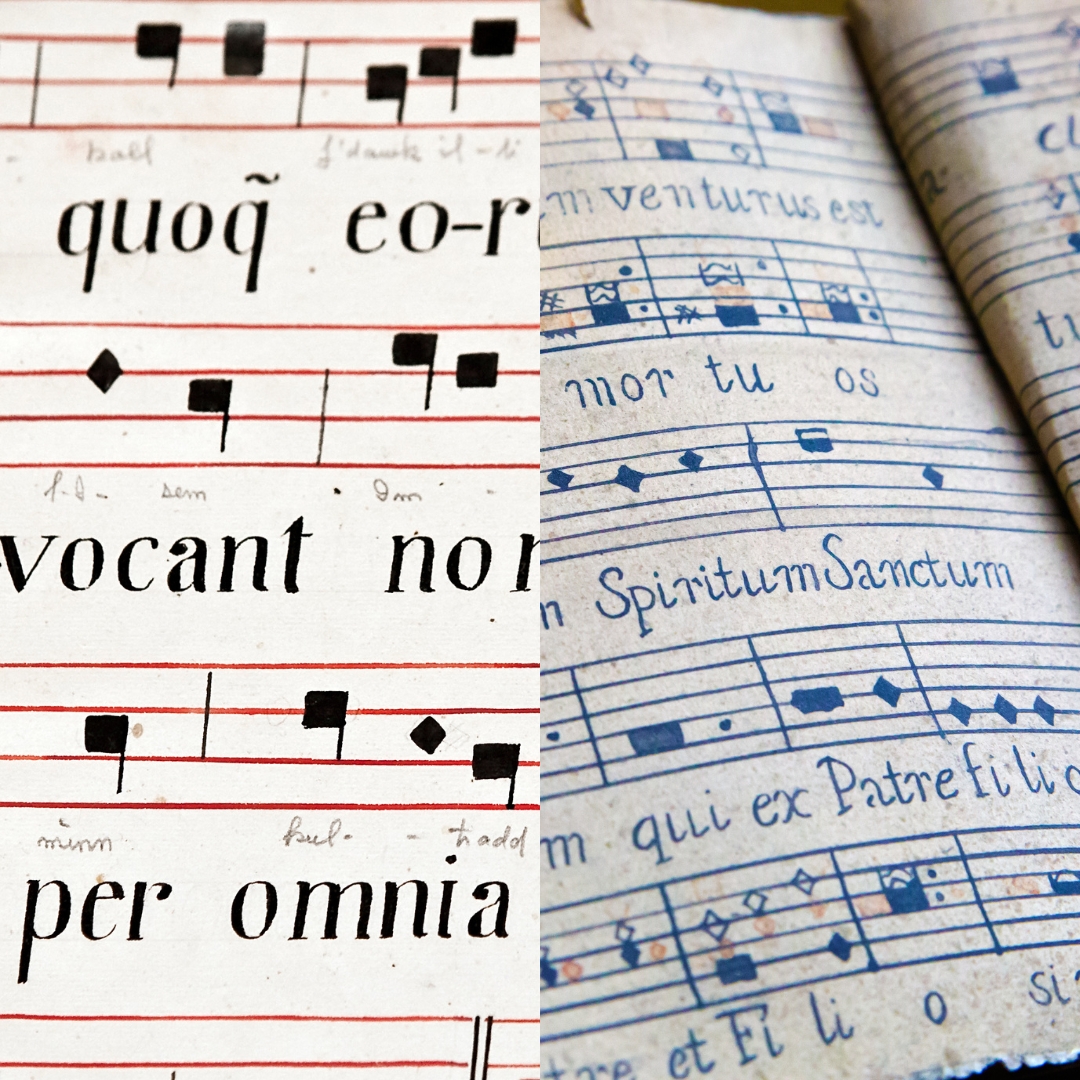

Für Alina reinforces the plainchant connection not only in its use of musical texture and tonality/modality but through the way it is engraved. What I mean by this is how it is scored visually, as sheet music. As we can see, Für Alina boast similarities with plainchant music through its use of note heads. Für Alina only uses filled-in note heads and semibreves, making rhythmic details more ambiguous. Relatable to plainchant, this gives the performer(s) freedom.

Für Alina, texture and early organum

Für Alina is reflective of early organum and medieval music, where polyphony and counterpoint start to emerge. Organum often used two voices: a melody and an accompaniment voice. Unlike later counterpoint techniques that emphasised contrary and oblique motion, organum was much freer. It frequently used similar and parallel motion.

Für Alina is remarkable as it only uses two voices in similar and oblique motion. There is some parallel motion but this is limited due to the restrictions of the left hand, which we will come on to. There is no contrary motion in the entire piece. Pärt’s disciplined exploration of tintinnabuli is the reason for this, which we will now discuss.

In the video below, you might note how there are no stems on the notes. Für Alina’s notation is a reflection of this, as is the omission of time signatures. The use of bar lines is similar too. Although the organum composition below has longer phrases and uses a tick style bar line, probably to denote a break point.

Rules of Counterpoint: Tintinnabuli & Für Alina

M-voice and t-voice

In the earlier section, I briefly mentioned the concept of m- or melodic-voice and t- or tintinnabuli-voice. In Für Alina, the m-voice is in the right hand/treble part and has the freedom to play notes of the B-aeolian (or natural minor) scale, while the t-voice can counterpoint notes by playing notes only of the B-minor triad. The distinction and relationship of these voices will become important as we dive deeper into the compositional technique of Fur Alina.

Motion and voice-leading

Startlingly, the counterpoint of Für Alina is exclusively in similar, parallel and oblique motion. The result of this is a pair of voices that never move in opposite directions (contrary motion). This likely comes as a confluence of other restrictions. For example, the tonal implications of having the t-voice occupy the root triad mean that, while dissonance and consonance can exist, harmonic tension does not. Furthermore, Pärt avoids the octave and unison, at least in Für Alina. Contrary motion, with the restrictions of the voices would likely have led to an octave or unison.

The omission of contrary motion comes from what seems to be an aesthetic restriction that Pärt imposes on himself. In analysing and discussing Pärt’s work, musicologist Paul Hillier identifies a series of relationships that can occur between the m- and t-voices. One of these is the distance between tones, referred to as 1st or 2nd-position. The second is the relationship between voices that are either superior or inferior. (There is also an alternating relationship, but this is essentially where the relationship switches from superior to inferior, and vice-versa.)

Interested In Learning How To Compose Tintinnabuli? If so, I am currently offering the first chapter of my new tintinnabuli composition course for free here.

Positions explained

The concept of a 1st or 2nd position comes from the distance between the voices. What defines this distance is the presence (or non-presence) of a triadic tone between the two voices. As we have established: Pärt avoids octaves and unisons in Für Alina and restricts one of the voices to notes of the B-minor triad. The result of this is two positions when one considers voice relationships as well.

The 1st position is where the m-voice is as close as it can be to the t-voice without being the same pitch. Furthermore, in the 1st-position, there should not be another triadic tone between the two voices.

The 2nd-position is where the m-voice is as wide apart from the t-voice as it can be, without being or exceeding the octave.

The easiest way of visualising this is to think of the 1st and 3rd of the root triad. In Für Alina, this would be B and D. If we imagine the top line, the D, is the m-voice, this means the note can move down a step without the position of the voices changing. However, if we move it upwards, the distance becomes a 2nd-position. The reason for this is there is a triadic tone, the D, between the B and E. To maintain the position, we would need to raise the T-voice upward from B to D.

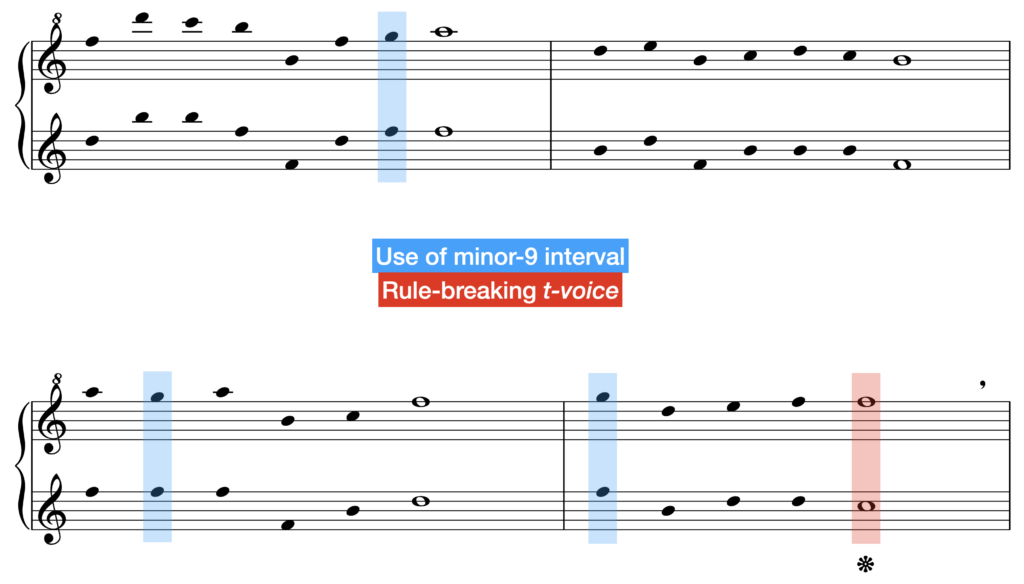

To demonstrate the positions and relationships more clearly. I have, below (Ex.4), created a series of harmonisations on bar 8, using the different positions and relationships. Labelling each one, note how, for the superior relationships, the t-voice is positioned above the m-voice. Also, how in 1st position, when transposed into a closer octave, there is no space to put a different triadic tone. Likewise, there is only space for one triadic tone in the t-voice, in the 2nd position examples.

In their 1976 composition, Für Alina, for solo piano, Arvo Pärt introduced the world to his algorithmic technique, tintinnabuli. At first glance,

Für Alina's counterpoint

If we combine the relationship and positional definitions we have just learned, we can make some important observations regarding Für Alina. As we have said already, it avoids the use of contrary motion. However, the reason for this may lie in Pärt’s decision to maintain an inferior, 1st position relationship between the voices throughout the composition. (Excluding one point that I will come to.)

Assuming that we transpose the two voices within an octave of one another, this means there is never a triadic tone between them (1st position). And, the t-voice never goes higher than the m-voice (inferior relationship).

Für Alina's voice switching climax

Pärt creates a climactic moment in Für Alina through the changing of position and relationships between the voices at bar 11. The left hand, in this bar, drops to a C#. This is notable in the obvious sense that the t-voice leaves its restriction of only performing triadic tones. However, this is because the roles have switched. The right hand, or what was previously the m-voice, moves to an F#. It is a hugely significant moment, as it is the one point that the position becomes a 2nd-superior relationship between the voices. In other words, the t-voice and m-voice not only switch positions but their span is extended so that another triadic tone could be placed between them.

Pärt actually further accentuates this moment with a comma and break in the piano sustain pedal. Furthermore, in the build-up to this section there are several uses of the dissonant minor-9th/compound-minor-2nd interval (ex.5). While not climactic in the sense we might think of a Tchaikovsky finale, there is a sense of shape and punctuation to this passage of the music. Pärt draws attention not through dramatic, but subtle changes. Introducing greater intervallic dissonance, leading to a switching of the voices and positions, there is a subtle imposition of climactic shape given to the composition here.

Structural symmetry and infinitude in Für Alina

Lastly, I want to highlight the symmetrical structure of Pärt’s Für Alina. From bar 2, if you look at the score of Für Alina and begin to count the notes of each bar/phrase, you might start to notice a pattern emerge:

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 (3)

If we ignore the final bar, it is a palindromic or non-retrogradable sequence. The numbers go up sequentially to 8 and then count down in the same pattern. If we read the sequence backwards, it is exactly the same. However, including the final bar raises a question? Is this the end?

In the recording given at the start of this article, the performer-uploader repeats the track. Similarly, the recording below loops the track several times. The performers have clearly identified this infinite quality in the piece and want to emphasise it. That or they just want people to hear them play for longer… classic performers.

Follow us.

Summary

I always remember my PhD supervisor giving a lecture on complexity and simplicity in music when I was an undergraduate. Essentially, he implied that Pärt’s music while seemingly simple is actually incredibly complex as its austerity causes us to go searching for more. And, that is the beauty of this piece from a compositional perspective. It is so compact and clearly uses a set of rules, giving us plenty to take from it.

We have identified several techniques that we can take and reapply to our writing of a tintinnabuli piece, or more widely. These are:

- Inspiration lies in all forms and can influence a composition in many ways. Pärt appears to have been influenced either consciously or sub-consciously by religious and medieval music and sonic stimuli.

- Restriction can lead to ingenuity and clarity.

- Breaking and playing with the restrictions you impose on yourself/construct can be used to create shape and interest within a work.

Sources

Griffiths, P. (2010) Modern Music and After. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jon Anderson (2019) Part’s Fratres, tintinnabuli construction.

Milton Mermikides (2020) Arvo Part’s Sacred Minimalism [Video].

Price, P. Rae, C. B. & Blades, J. (2001) Bell (i) [Website]. Grove Music Online.

Whittall, A. (1999) Musical Composition in the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia. (2020) Arvo Pärt [Website].

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …

Pingback: The Flag Parade - Music Composition Techniques - Any Old Music