Readers look down, video watchers click above!

Vaughan-Williams’ Dives and Lazarus is a compelling exploration of string writing techniques. By no means avant-garde in the string techniques used, it relies on simple effects that are largely built around the concept of divisi. However, these simple effects are used to dramatically extend the colouristic range of the string orchestra. There is, after all, not only a great difference between instruments and sections of instruments, but also the sound of one, two, three or eight of the same string instrument and, even, the particular strings they use.

The primary concept that underpins Dives and Lazarus is divisi. (See, nothing extravagant.) How then does RVW make this straightforward technique so potent in this piece? Well, it is how he specifies these divisi’s and asks players to perform the music within their divided sections.

To demonstrate how RVW uses divisi, I present five examples (in no particular order) of how he uses the technique. In so doing, I use the following terms to distinguish them:

- Same strings different string

- Antiphonal voicing

- Solo-section doubling

- Divisi-section doubling

- Divisi by desk

Score Video

1. Same strings different string

A slightly confusing name, granted. However, I think its quite catchy, in a way that makes it more memorable once you have the gist of it.

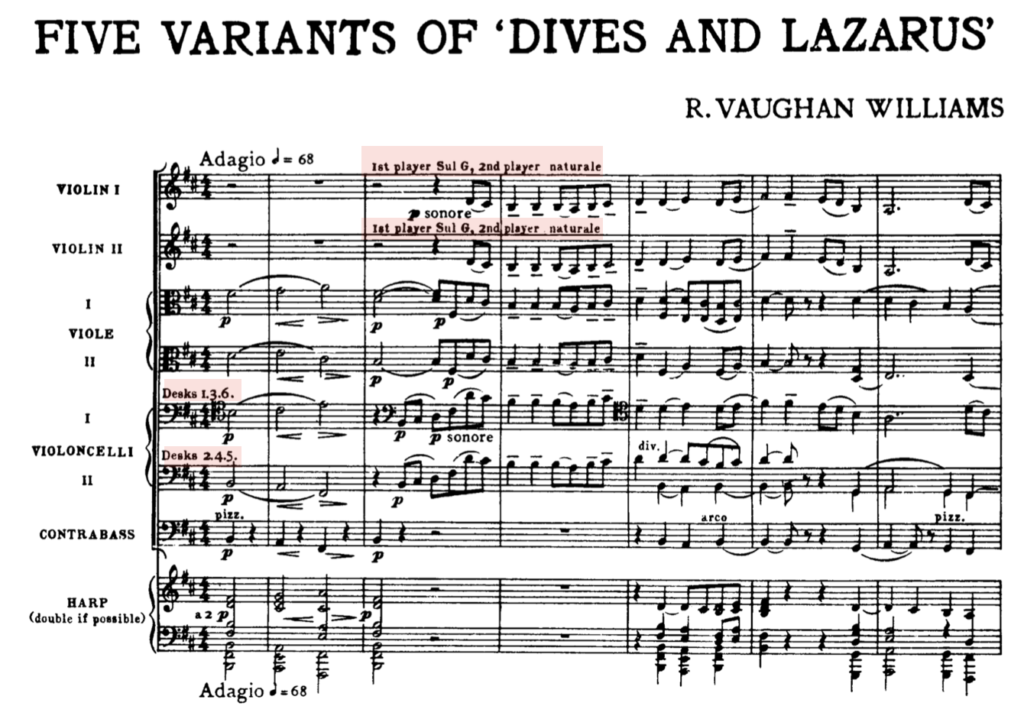

Same strings different string technique instructs divisi in one part, but all the players play the same line. Instead, the divisi tells some players to play naturale and others sul-G. What this means is, half the players play the music how they would, without any specification, choosing what strings and, thus, string position to use for different portions of the melodic line. The other half of the string section play the whole line on one string, the G-string (sul-G).

The below example demonstrates RVW’s use of “same strings different string” at the beginning of Dives and Lazarus. We would usually anticipate the whole section to change or remain on the same string together. However, when the melodic line goes into a range where the D-string becomes available, the tone colour will be subtly different. The reason for this is the different qualities of each string.

In my trusty orchestration manual, The Study of Orchestration by Samuel Adler. There are descriptions of not only string instruments but the characteristics of individual strings on those string instruments. For the violins, he describes the G-string as “most sonorous… as the player moves into the higher positions, the sound becomes very intense”. Similarly, for the D-string he describes it as “mellow”, “probably the least distinctive… yet it can exude warmth and lyricism”. As a result, the divisi here will result in a blend of these timbral qualities. Rather than having a completely sonorous and intense tone, had all the strings played sul-G. We get a mixture of intensity and warmth.

Looking at the example, you may ask, why not just ask the 1st violins to perform sul-G and the 2nd Violins naturale. Well, I think this links to the second point: antiphonal voicing.

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves

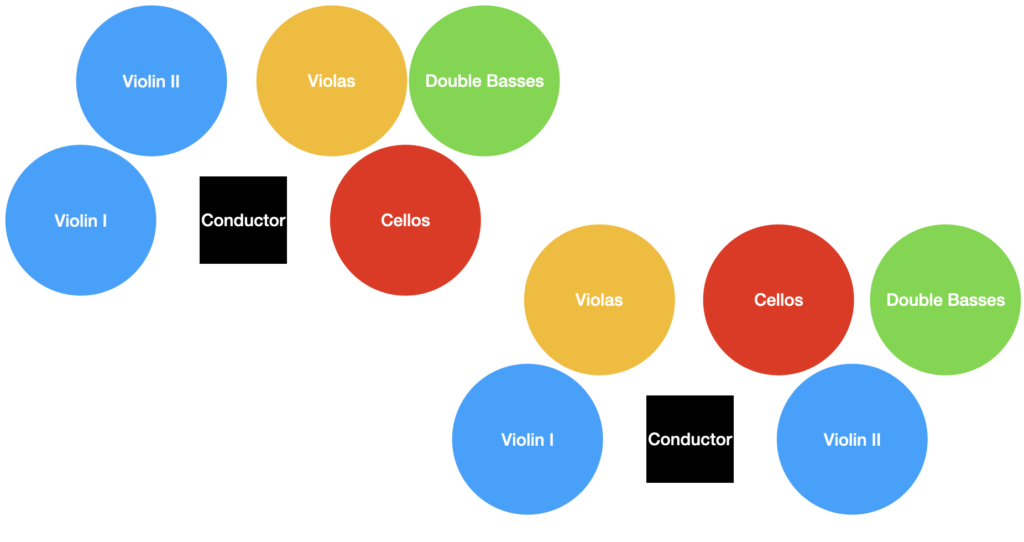

2. Antiphonal Voicing

Moving on to the second example of RVW’s extended use of divisi, antiphonal voicing, in this instance, is essentially the consideration of panning. At this time, the standard set up was for Violins 1 and 2 to sit opposite one another. On the left of the conductor, you would get Violins 1, and on the right, Violins 2. Nowadays, orchestras still use this setup, particularly for media/studio recording, but many prefer to have Violins 1 and 2 next to each other.* Laying the orchestra out with Violins 1 and 2 opposite each other invites antiphonal thinking. Or, in other words, it invites one to consider panning as a compositional device or effect.

*(For me, it depends on whether the strings are solo or sectional and the situation. In recording chamber groupings, I’d probably want violins together. In recording sections, I would prefer the violins opposite. In a live performance, I’d probably want the violins next to each other.)

Antiphonal/panning considerations were important to RVW. Another earlier composition, Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis, is evidence of this. In writing for different orchestras, using antiphonal (call and response) textures, there are three separate ensembles:

- A string quartet

- Orchestra I

- Orchestra II

The ensembles occupy different locations within a performance space. As a result, the technique creates distance/3-dimensionality through the acoustic effect that the spatial positioning imposes.

In Dives and Lazarus, the effect is much more modest but still significant. The effect is more stereo (RL) than binaural (3D). Furthermore, It also offers a reasonable answer to our previous question:

Q. Why not have one violin section use sul-G and the other natural?

A. Because the violins, sat opposite each other, would be less blended. We would have the string sound of Sul-G on one side and naturale on the other. A potentially intriguing effect, RVW wanted the timbre to be whole and blended, as opposed to separate.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

3. Solo-section Doubling

Solo-section doubling is the use of a solo string instrument to double a melody line that is also being played by a full or divisi section of a different kind of instrument. Typically, the solo instrument is in a distinctive and, usually, stronger register than the other instruments it is doubling. The reason being it is numerically disadvantaged and, thus, needs to rely on being particularly sonorous or incisive if it is to add anything to the timbral colour overall.

The result is similar to the first “same strings different string” technique. However, depending on how exactly it is done, it is a little more 3-dimensional. What I mean by this is the sounds are a little more separated. This is because the solo instrument sits forward, with more presence, cutting through the texture as a single voice, while the sectional voices give it “fluffy” (technical term) edges.

Like individual threads of a string, the solo-voice is wirier. Less strong, it stands a better chance of cutting through. Whereas, the section is a string made up of many threads. Less able to cut, it is stronger. If the instruments were the same, the thread would just be a part of the larger piece of string. However, as it is not, the individual thread sits ahead, in the centre of the string as a slightly different colour.

RVW uses this doubling, divisi technique briefly in parts of Dives and Lazarus. The first time is at rehearsal mark A. Here he uses a solo cello, on its A-string, to double a unison section of Violas. The cello and its A-string register are particularly good for this as, like with most top strings on string instruments, it is the most brilliant. (Whereas, the lowest is frequently the most iconic and sonorous.) Therefore, it cuts through textures with greater success and character.

I experimented with this technique recently, using sampled string sections, doubled by recorded solo strings. In this context, it was particularly interesting as the environment was highly controllable. Using samples and multi-tracked solos I could boost or reduce levels to get the balance and colour I wanted. (See video below where I timestamp some points of interest.)

I particularly like this technique as I think it is not only interesting to play with, but it is easily implementable, encouraging experimentation. Antiphonal voices are implementable too and, with certain sample libraries, you may be able to create the other divisi effects. However, either using sample libraries or hiring soloists, which is doable on smaller budgets, you can play around with the effect more easily.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OYqfTcI3Ztk&t=9s&ab_channel=AnyOldMusic Paul Dukas’s The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897) is a musical composition based on a poem, of the same name, by 18th-century German writer Johann

4. Divisi-section Doubling

Divisi-section doubling is similar to solo-section and the “same strings different string” example, in that they blend instruments from different sections. However, unlike solo-section doubling, there is less extreme dimensionality in the sense that there is a single superimposed part layered on top of a section or divisi part.

Similar to the “same strings different string” divisi technique, however, this technique uses and blends the characteristics of different string sections as well as the timbre of divisi sections themselves. Doing so leads to a richer colour, with plenty of instrumental numbers, through the use of mixed timbres, strings and tessituras.

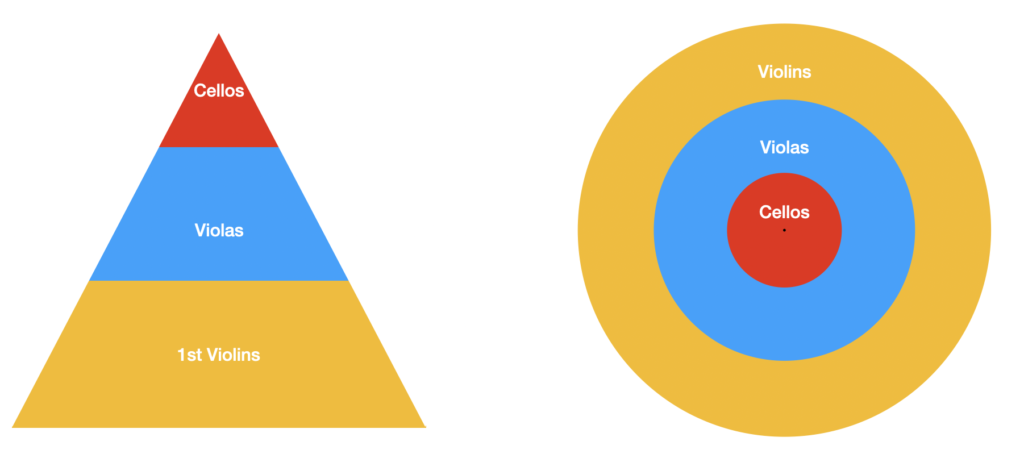

If we look closely at the extract below, we can see a passage that uses divisi celli, divisi violas and unison first violins. The violins are also asked to play the passage on the G-string. The line, despite being the main melodic interest here, is in the middle of the texture. Very briefly, it is actually the lowest sustained ‘arco’ voice. Each part is piano dynamic, so Vaughan-Williams chooses to rely on instrumental numbers and the interesting colouristic blend of these three instrument types to allow it to cut through the texture.

In this brief passage, we will not only have the sonorous sound of the first violins’ G-strings. We will also have the body of the distinctive viola sound and the brilliance of the celli on its A-string. In this way, we could almost start to visualise the sound as the cross-section of a cone, with the celli at the point, violas at the mid-point and violins at the bass. We can then peer down on the top of this cone and see a far more vibrant series of colours.

5. Divisi and sub-divisi by desk

For this last technique, I can only speculate on whether it offers a different timbral effect or is a consideration more of performance and player/section interactivity. I’d be interested to know other peoples thoughts and knowledge on this, so get in touch if you do! (Contact.)

At several points of Dives and Lazarus, Vaughan Williams specifies a divisi by desks, or for one desk to support another part. Typically, there are two players to a desk, within a string section (depending on numbers… and social distancing!). Therefore, a single divisi (not a divisi into 3 or more parts) usually splits each desk in half. So there is one player on a desk playing one line and the other player plays the second line. While this might require some negotiation, depending on how the lines interact, dividing this way has become something of an orchestral behaviour string sections simply do.

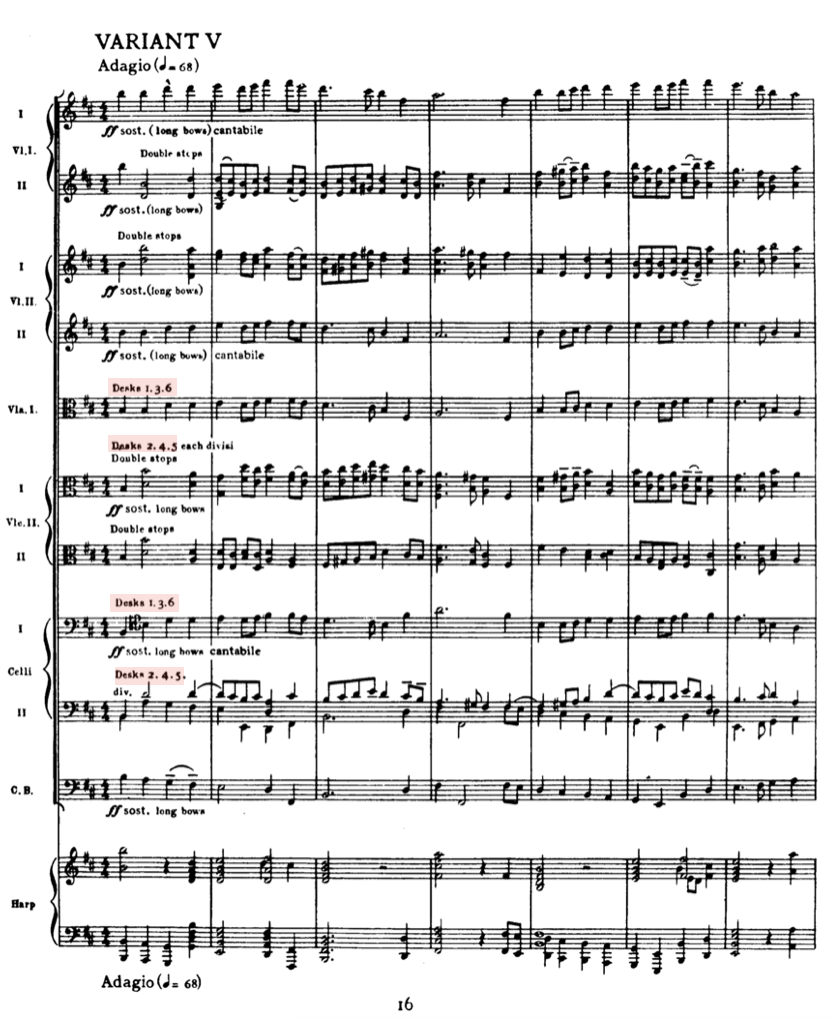

In the case of Dives and Lazarus, RVW frequently asks for a divisi of desks 1, 3 and 6 in one part and 2, 4 and 5 in the other. Sometimes, like in the below example (variant V, opening), this seems to be a way of managing numbers and further divisi’s. Where the first trio of Cello desks (1, 3 and 6) take up a line that unison doubles the same trio of desks of the violas, the second trio (2, 4 and 5) divide again.

In Celli II the divisi will likely be a standard division across players on each desk. Therefore, RVW can add a contingent of players to double the Violin-I-2nd part at the octave, supporting that line. He is also able to blend the other three cellos with the double basses at either the octave or unison (it changes through the passage).

This divisi effect may have a further value that RVW was exploiting, although I can only speculate based on my knowledge and experience. For instance, it may alter the sound quality slightly, due to the cellos being paired in both closer proximities, but across the section. In the case of recording, this might be an interesting effect to experiment with. However, in a concert hall performance, I would be surprised if it affected the sound very much at all for the listener, due to the space between the listener and orchestra.

RVW could well have been exploiting the psychology of the ensemble performers. Gesture and teamwork are a part of orchestral playing. So, thinking about the divisi from the perspective of the individual player. Having paired desks would make the individuals feel more like they are still within a section. Whereas, a traditional divisi might not as the players may be more cognizant of the divisi and, thus, ‘play out’ when RVW would rather they did not.

Dives and Lazarus has a subdued quality to it. Quite impressionistic in the way it hues and blends more delicate string sounds. Therefore, while ironically thinking of each player as an individual within the string orchestra, he wants to suppress that idea amongst the players (unless he specifies solo). In dividing by desks, RVW may be wanting the players to be reminded that they are not a soloist, but an ensemble player, part of a larger organism responsible for bringing the music to life.

Summary

With some of these divisi’s their use is self-explanatory. However, with some we have to speculate on Vaughan Williams’s reasoning. However, in these observations and speculations, we can start to spot interesting ways of enriching and experimenting with our use of the string orchestra. These experimentations could be with a string orchestra alone or the string orchestra within a wider orchestra.

Of course, many of us are limited to samples when it comes to string orchestras. I certainly cannot afford one on retainer. However, some of these are more than easy to experiment with while using samples. Especially given the growing forms sample libraries come in, with soloists and divisi performers. This being said, I would recommend any composer or orchestrator look at using recording soloists to combine with their samples, even if they are restricted by smaller budgets. In my experience, it provides valuable learning and is very worthwhile and personally enriching.

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …