Teresa Amabile’s book, Creativity in Context (there are no affiliate links in this article), is one of the very few texts that I can say definitively changed my thinking and approach to musical composition. Reading it was a personal, paradigm-shifting moment where I started to understand what music composition and wider studying of music meant to me. Or, at least, what I wanted it to become, where before it was uncertain and ambiguous.

In this article, therefore, I will attempt to unpack some of the core concepts from Creativity in Context and discuss why I found them significant. The first half will do the unpacking. Briefly, it will offer an overview of Amabile’s underlying thesis: what is meant by a componential theory, which she presents. I will then give some brief definitions of the components and discuss how they come together to form a reduction of the creative process. In the second half, I will attempt to articulate why I found these meaningful to my approach to music composition.

Componential Theory/Model

Without unpacking the entire history, study and discourse on creativity, which I would not be qualified to do anyway, there is a clear link between Amabile’s componential theory of creativity––that is to say it is made up of units(, components or parts)––and a very early theory on creativity, known as Staged Theory.

An early 20th-century thesis, by Graham Wallas, the staged theory of creativity essentially breaks down the creative process into four phases, which I try to offer extremely brief definitions below:

- Preparation: the gathering of information about and for the problem to be solved.

- Incubation: the gestation or subconscious mulling over of the information and problem.

- Illumination: the light bulb moment where your subconscious hands over a potential solution.

- Verification: the act of exploring and testing the solution to see if it is suitable.

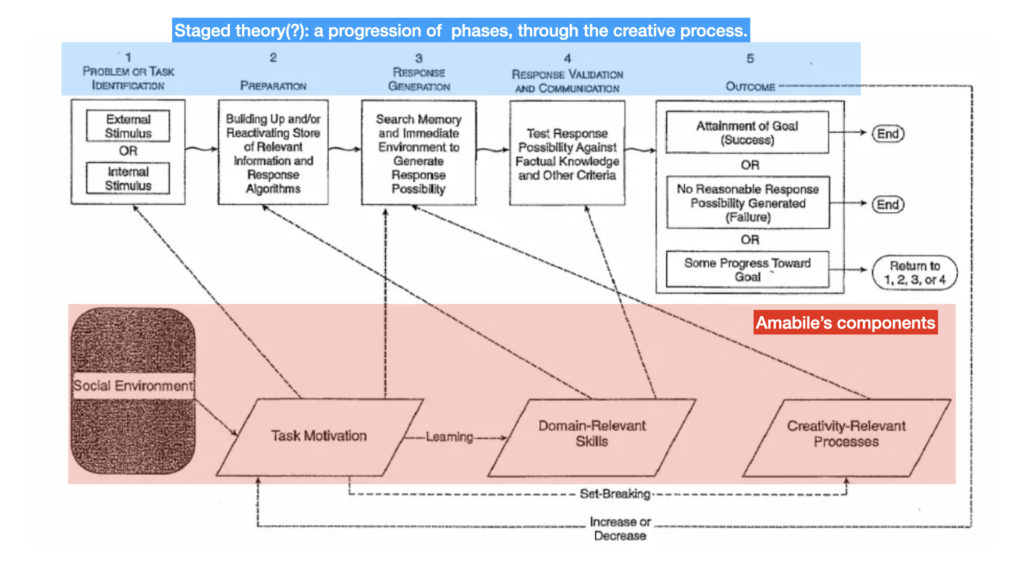

Amabile’s componential theory runs alongside a critiqued, adapted version of the staged theory. Furthermore, her componential approach explains what is happening at each stage and how the individual and their working environment influences their creativity. In doing so, she––rightly in my opinion––emphasises the iterative nature of most creative tasks. In other words, the gradual, step-by-step approach to reaching a creative solution. As opposed to the sudden realisation of an entire artistic work or scientific theorem.

In addition to this, Amabile’s staged reduction of the creative process focuses on the observable, active work involved in creativity. What I mean by this is that her work is grounded empirically in the observation of people working on creative tasks. As a result, her phases focus on actively working toward a goal, where Wallas’s define different phases of conscious and subconscious working.

Below this paragraph there is a diagram of a model taken from Creativity in Context. It demonstrates what we have just been discussing regarding Amabile’s componential theory of creativity. Note how along the top we have what could be Amabile’s “stages of the creative process” and, below this, the components of her theory. It also demonstrates other connections far more concisely than I could attempt to unpack here.

Bernard Herrmann’s “Walking Distance” is full of different orchestration and composition techniques. Last week we focussed on some of those orchestration techniques, such

The Components

Before discussing the significance of Amabile’s thesis and concepts, the four components of Amabile’s theory are social environment, task motivation, domain-relevant skills and creative-relevant processes.

Domain-relevant skills

Domain-relevant skills are an individual’s knowledge base, experience and practice within the field or fields that a creative problem presents itself. An individual develops their knowledge base through study and may do so in direct preparation for a creative task. They draw possible solutions to their creative problem from this knowledge base and use these relevant skills to determine the value and validity of their potential solutions, deciding, ideally, upon the most valuable.

Linking to my previous article on Overcoming Writer’s Block, it could be seen as playing a valuable role in understanding and defining the conceptual space within which you are working. In other words, you require prior knowledge in your field to understand it and determine that creative responses are aesthetically commensurate with that space. Forming a conceptual framework, therefore, allows for a more confident verification process.

Creative-relevant processes

Creative-relevant processes are an individuals innate “cognitive style” and “personality characteristics”. In other words, how we consider and understand problems are vital to our response generation. How I think is different to how you think, although we might have similarities in some areas( and vast differences in others.) For example, I might be more inclined to think laterally and “synthesise” ideas from different domains. However, you might have a “greater tolerance for ambiguity”. There are many subtleties to how each of us deals with whole or facets of creative problems. It is these individual, inherent subtleties that this component encompasses.

Task Motivation

Task Motivation is our desire to work on a problem. How that desire emerges is critical in positively or negatively impacting our creative potential. If the desire is innate, our willingness and want to work on the project will be greater, which will have significant, positive ramifications on our work. Whereas, if the desire is not there, but something or someone is making us work on a creative task, then the impact is detrimental. In essence, we do our best work when it does not feel like work: it gives us meaning and a sense of pleasure and purpose.

Social environment

The social environment is the context within which an individual or group are working and how this affects creativity. For example, highly critical superiors or the imposition of deadlines hurts creativity. Whereas working environments that encourage risk-taking (in a creative sense!) and greater creative autonomy usually see creative people flourish.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up for our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

The significance of Amabile’s thesis

I discovered two important revelations within Amabile’s work, which altered my understanding and approach to musical composition. I want to discuss these discoveries concisely here. These are, firstly, that creativity is a process of iterative learning and development: both in of itself and across multiple creative tasks. Secondly, creativity is not just something that we do in our heads, but in a location, possibly with other people, certain tools and over a period of time.

1 Creativity as iterative learning and development

We can see creativity as iterative learning and development in Amabile’s model to demonstrate her theory (presented earlier). In the interconnection between preparation, as a phase in the creative process, and domain-relevant skills, as part of an individual’s creative potential, there is a clear feedback loop. In preparing to meet the creative challenge, we practice and study, building our knowledge and expertise. To put it another way, the process of composition is a process of learning and discovery. We discover new ways of ordering and articulating musical ideas, each time we attempt to go through that activity.

If we consider the whole creative process as a representation of music composition, we can begin to identify a circular, repetitive quality. In a music project, we may study and then attempt to create ideas based on that practice. However, we may fall short of composing the piece we want or need to. Therefore, we have to repeat the process, hoping that we get closer each time. Amabile’s fifth stage, “5. Outcome”, demonstrates this. We iterate toward our goal: study, ideate, verify, repeat (if necessary). Or, study, put study into practice, verify, repeat (if necessary).

On a larger scale, in achieving our goal (or attempting to, at least), our expertise is grown. Some of this knowledge might fall away, but some will stay, remaining useful in future projects. The relevance of the experience may vary. In future compositions, some skills be directly useful, some laterally, and some not at all. However, the process repeats and we learn each time we compose.

Iteratively, in a project, we improve ourselves to rise to a challenge. Iteratively, project by project, our expertise is grown.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QYUPk1vKxQk&ab_channel=AnyOldMusic Witold Lutosławski’s Chantefleurs et Chantefables is a song cycle for soprano voice and chamber orchestra, completed in 1991. Textually, the songs

2 Creativity happens in a place and time

It is easy to forget or not be aware of this: we have to create somewhere. In Amabile’s model, she identifies how the social environment––although I would extend this to be an environment more generally––impacts a person’s creative potential. Usually influencing task motivation, which has a substantial knock-on effect, our working environment can considerably determine how effectively we work toward a creative solution. We should be mindful, therefore, of how our creative environment influences our work.

For me, understanding how your creative environment impacts motivation makes me think about what I need at a given phase of the process to achieve what I need to. For example, do I need a feedback mechanism to create my music. If so, will my trumpet, piano, or sample instrument or instruments help or hinder me? Could the shorter feedback mechanism help motivate me or lead to my motivational demise?

Sometimes I find it helpful to imagine or develop an idea more fully before trying to verify it. Therefore, being in an environment where I cannot access a feedback mechanism could be motivating and, thus, helpful to my creative endeavours. Alternatively, maybe I need to study or practice something before I can ideate. In this case, setting up a location free of distraction, where I can only analyse a score with absolute focus, could be beneficial.

Music composition is multi-faceted, and not all environments are equal. Furthermore, some are more specialised than others in ways that are not always obvious. So often, we can set up a space that we hope can serve all parts of our creative process. However, this, in my opinion, leads to a “master of none” situation. One environment might help us define, practice or ideate, while another might help us verify our work. It is context dependant.

Close: further reading and watching

Hopefully, my efforts to discuss this book has proven insightful, and my efforts to articulate its personal significance has added to this commentary. I present a whistle-stop tour of Amabile’s concepts and thesis, so please do not judge the work on what I say here. If you are interested to know more, here are some helpful links:

The book: Creativity in Context.

A video of Amabile giving a brief intro to her ideas: Teresa Amabile – Creativity and Motivation.

A nifty “working paper” that is freely available online, giving a concise overview of her work: “Componential Theory of Creativity”.

I consider the study of creativity to be one of the most valuable efforts I have made, over the past 6-years, to better myself as a composer. Having a better understanding of the mechanics of creativity means I can, when I need to, be mindful of what I am doing. While this is, ironically, a negative creative state, as I have exited that free-flowing state of play, it does give me an idea of how to work back to that state. For example, I might need a break to feed my mind or body. Or, I might need to change my workspace. It is not clear, but it is more persistent.

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …