Video lovers, look up! Readers, start scrolling!

In this weeks article, I want to discuss a book that shook my foundations as a composer. Written by philosopher and cognitive scientist, Margaret Boden, the book is a compilation of essays called Creativity and Art: three roads to surprise. Interested in artificial intelligence and the concept of artificial general intelligence (AGI) the essays explore and seek to understand human creativity through the problem of computational intelligence and creativity.

From my perspective as a person who tries to be artistically creative in practice, I found the concepts presented in Creativity and Art fascinating. The reason being that, much like how music theory can reduce music compositions to a form or structure that makes them digestible, they can end up barely resembling the original piece. Similarly, doing so with creativity produces a similar detachment and potential dissonance between theory and practice. However, it is this dissonance and ambiguity that makes the concepts in Boden’s essays, in my opinion, so seductive.

As essays, Boden is positing her ideas, working out her thoughts through writing, rather than suggesting she has uncovered absolute truths regarding creativity. However, it is in these developing ideas, on such a broad subject that so many questions emerge. For instance, from what perspective are we understanding the creativity behind an artistic artefact? In other words, are we interpreting the creativity of another person, through a thing they created? And, if so, is that the right way to go about it? The essays themselves seem to switch perspective. However, for myself, I’ve found the concepts Boden unearths compelling in trying to understand my practice: the creative approaches I take as a composer.

In this article, therefore, I want to focus on the concepts and why I found them significant. In doing so, I pick out three concepts. Two of these are explicitly outlined in the essays, while the third appears implicitly as a result of the discourse. These are:

- P- and H-creativity

- Combinational, Exploratory and Transformational Creativity, which constitute the “three roads to surprise” in the books sub-title

- Conceptual Space

P- and H-Creativity: what in the heck are these?

P-creativity or Psychological-creativity is something that you do, learn or create that is inventive to you personally. For example, maybe you write a fugue. To you, this could be a significant creative feat as it is the first time you have written a fugue. You feel accomplished (and so you should). However, to the world, unless you’ve struck on some piece of untouched musical magic, it’s not historically creative (h-creativity). A fugue is an old form of music, well-traversed by many composers. Therefore, it is defined as p-creativity: significant to you creatively, but not the world and music history.

Conversely, h-creativity is historical creativity. So, in extending our fugue analogy, Bach is often attributed as the father of the fugue. Not necessarily because he devised the form as forms themselves tend to emerge over time, but because he did many remarkable and historically creative things with the fugue. For example, The Well-Tempered Clavier is a historical feat in western classical composition, as composing fugues and preludes in the 24 major and minor keys was novel in the 18th-century. To an extent, it held importance from an artistic and scientific perspective due to its exploration of the new well-tempered tuning system. Therefore, it has become regarded as historically significant and, thus, h-creative.

Imposition of Logic

What is significant about this distinction is that it imposes an uncomplicated logic on how we can think about creativity generally. While psychological creativity can occur on its own, historical creativity cannot. To create something historically creative, you must be discovering or doing whatever you’re doing for the first time as well. Therefore, P-creativity can exist alone; h-creativity must be p-creative too.

Why do I find the concept of p- and h-creativity significant?

I found this concept notable as it made me aware of my previously naive approach to music composition. In combination with another book, Creativity in Context (by Teresa Amabile: book link; link to video summary by author), which I will likely discuss in the future, it made me realise how cripplingly stupid it was to so doggedly pursue and expect originality. Every composition felt like it had to reinvent the wheel if I was to compose something musically meaningful.

You would probably think the concept of p- and h-creativity would have had the opposite effect and reinforced my previous approach. Without Creativity in Context and other influences, including other concepts within Creativity and Art, maybe it could have. Furthermore, it is not to say I do not seek originality, but realising the logic behind the fact that: to be historically creative, it needs to be the first time for you as well changed my approach to composition.

My approach now is to take incremental steps as opposed to trying to take one big leap. As opposed to reinventing the wheel, I try to look at the things I have done and determine how I can build upon them. What worked? What did not work? What did I like, and how can I do it better next time? My logic being that if I find and do enough p-creative things, I stand a much better chance of creating something of h-creative value. Although, if I do not, nevermind!

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Norman Del Mar’s engaging and informative writing provides unique insights into instrumentation and the lived experience of a knowledgeable conductor and horn

Combinational, exploratory and transformational creativity: what in the treble-heckers are those?

Combinational, exploratory and transformational creativity are ways in which we can engage in creativity. Or, in other words, they are forms that creativity can take: labels that we can use to try to distinguish them. I’ll now try to offer a concise definition of each.

Combinational Creativity

Combinational creativity is the synthesis of two or more disparate ideas to create something novel. Boden defines this form of creativity as the easiest. For example, we might combine salsa with Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. Here the arranger combines the familiar motif of Beethoven’s 5th with the tropes of salsa music. The listener’s interpretation and enjoyment, therefore, largely stems from an appreciation and awareness of said combinations.

A fun arrangement, this supports Boden’s further assertion that the ideas need to be familiar for the creative artefact to be appreciated. Although I only think, in practice, that matters from the audience’s perspective, which is not always the same as the creators. As a composer, you might want to veil the combinational origins. However, this is where the fuzziness lies in Boden’s argument. From what perspective or perspectives are we understanding the creative approach when discussing these concepts: the creator, the actor or performer, or the audience?

Sidenote: Another good demonstration of combinational creativity is Post-Modern Jukebox. They combine popular tracks with one or multiple styles of older pop music. However, the question, which I come on to, is whether this is only combinational and not a step into the exploratory and, even at time, transformative forms of creativity? Who decides and what perspective matters?

Exploratory Creativity

Exploratory creativity is where the creator identifies an aesthetic or conceptual space and uses it to inform their creative decision making. Or, alternatively, the thing you are creating becomes the vessel through which you are engaging and discovering things about a conceptual space.

Boden does not offer much explanation on what she means by conceptual spaces, beyond alluding to them being a form of widely understood aesthetics. Much like how an audience might appreciate the combinational creativity of a composition by identifying its components. An audience enjoys and critiques exploratory creativity through an understanding of the underlying aesthetic. This understanding may be implicitly understood or explicitly laid out, possibly by the artist offering programming information.

Exploratory creativity is more an exploitation and confluence of multiple tenets within an aesthetic. Therefore, the audience identifies this aesthetic-style/conceptual space and appreciates and enjoys what the artist has done within that space. The conceptual space acts, in a way, as the creative context for both artist and audience. Artist to create; audience to engage. (At least, that’s the theory.)

Transformational Creativity

Transformational creativity is similar to exploratory creativity in that it relies on conceptual space in much the same way. However, rather than creating or admiring the artefact as a confluence of characteristics that make it stylistically aesthetic. The creative artefact combines or does something unexpected with one of the characteristics, shifting our understanding or perspective of the conceptual space itself.

In comparison, as a generalisation, we might say that exploratory creativity is an effort to deepen understanding of a conceptual space. While transformational creativity is an effort to alter our understanding of a conceptual space. An example of this could be classicism and neo-classicism.

If we take Sergei Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1 (who did not like the term neo-classical…), in exploring classical style through the prism of his compositional craft as an early 20th-century composer and the time that has passed since the heyday of classical music in the 18th century. He creates a composition that counterpoints and deepens our understanding of classical music by making us hyperaware of its aesthetic tenets. In other words, he is exploring classicism. However, it also has a transformational impact through its historical detachment, positing the question “what might a classical composer compose now (or, rather, in the early 20th-century)?” In a way, neo-classicism is the conceptual transformation of classicism through revisitation.

Why do I find the three forms of creativity significant?

I find these three forms of creativity notable in many ways. One of these is that there is a dissonance between theory and practice. In that, the theory can delineate these forms of creativity. However, in practice, when you apply them to things, they become fuzzier around the edges. There’s no one arbiter of aesthetics. Cultures and societies may provide groups of general appreciation but even within those groups, there are individuals. Furthermore, they are incredibly fluid. We not only have different perspectives and roles as creators and creative observers, but our understandings of conceptual spaces are not uniform and as a result, subjectivity is inescapable.

Despite this, I think it is more than worthwhile, even helpful, to try and distinguish forms of creativity as a composer. The reason being they provide a way of understanding creativity that, at the very least, offers a means of trying to control it. What I mean by this is that if you are working on a composition, inspiration might not be striking. Understanding creativity in these ways offers a way in which you might be able to get the ball rolling.

If you find yourself stuck in a rut you can start to posit questions to yourself regarding these types of creativity. It could be, “what two or three things could I combine to create something quickly and novel?” Or, “what are the underlying aesthetic attributes, or conceptual space, of this composition?” For example, a few years ago I composed several cues for a video-game that parodied sci-fi thrillers and B-movies of the 40s and 50s. The beauty of this project was it established an aesthetic: to write the music in the style of these films. I, therefore, explored tropes, even cliches and the musical language of these films. As a result of this, rather than taking shots in the dark, the understanding of the conceptual space gave me a framework for validating my sketches, which made composing incredibly straightforward.

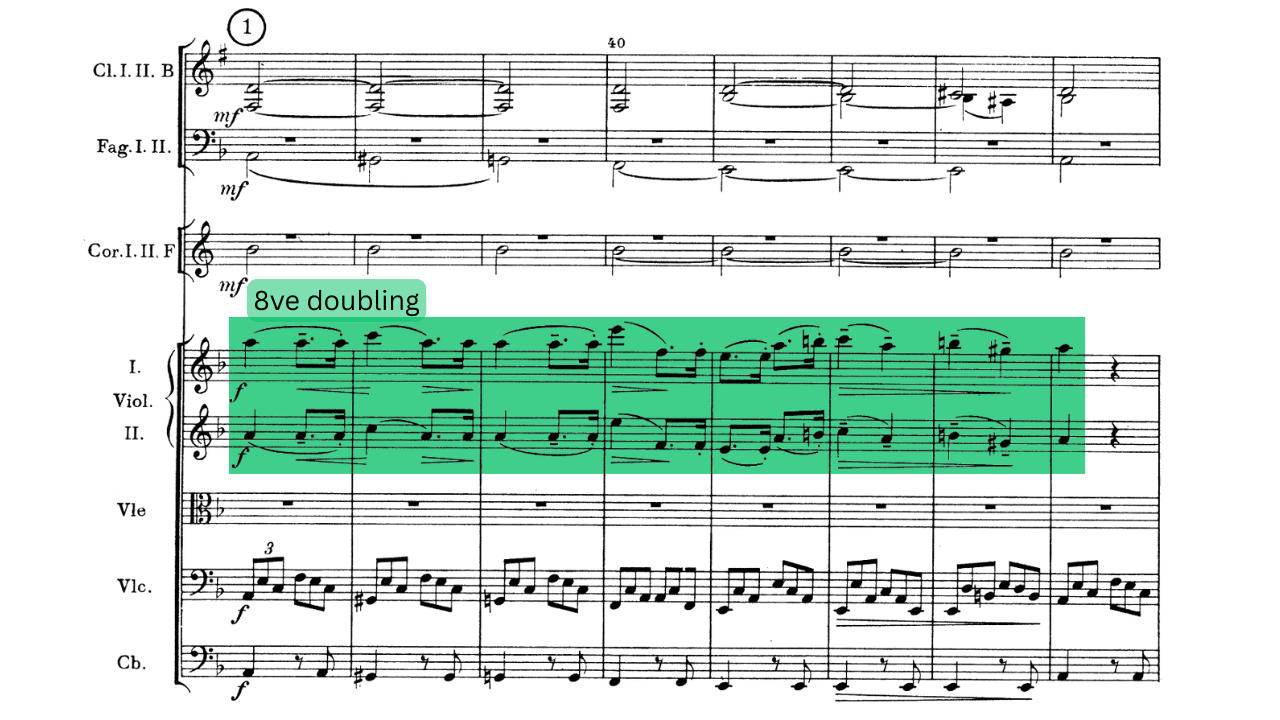

This week I was fortunate enough to stumble on a YouTube video by composer Zach Heyde. In this video he analyses the

Establishing Conceptual Space and expanding on the types of creativity

This is probably a good point at which to pivot into conceptual space. We have already established that it is essentially the aesthetic (or less aesthetic) qualities of a style. A creative artefact, in a sense, is the entity that comes from an individuals engagement with a conceptual space. Or, the critical perspective that an individual interprets and critiques a creative artefact from.

In combination with the types of creativity (combinational, exploratory and transformational), conceptual space becomes a kind of boundary. A boundary that might preexist, being constructed over time, or it might be one that we have to put up ourselves. This boundary delineates the area within which the creative individual or group creates their artwork. To make this easier to explain I like to form an analogy.

An analogy for Conceptual Space and composing

Thinking about conceptual space in this way and how we interact with it as composers, could be compared to planning a holiday. To have a worthwhile trip we probably want to define a few things that we would want to do on this holiday. Otherwise, our holiday stories will be pretty bland when we come home and friends and family (our audience) ask us what we did, and we say: “not a lot.”

Similarly, if we pick too much to do, not only could the holiday be exhausting or disorganised cacophony, where we cannot fit anything in, but so could the stories. Therefore, we want to pick out understandable things that allow us to learn about the place we have been to. Likewise, when we compose our stories for people, we pick out entertaining and communicable details, not everything.

Composing is much the same. We identify a conceptual space and we explore it through our composition. However, our compositions are not the trip itself but the story we tell of that trip. We don’t take all the details and nuances of conceptual spaces and throw them into a cauldron, hoping they make something nice. Rather, we cherry-pick the ingredients and try to place them together in a recipe. We compose a piece.

Follow us.

Summary

Boden’s essays are not presenting absolute truths regarding Creativity and Art. Rather, they present a developing discourse or snapshot into Boden’s incredibly deep thoughts on the matter. Furthermore, like with any theoretical exploration of something so complex the process of reduction or generalising creates ambiguities and dissonances between theory and practice. Just like the analyses I present of music on this website, there’s a degree of creative play demanded on the reader. You have to connect the dots between the reduced, theory, and the creative artefact: the practice.

It is in this creative play that the text has shaped my approach to composition so significantly. Inviting engagement and, thus, effort to apply and become more cognizant of my creative approach to music composition, the concepts have greatly impacted me as a composer and creative thinker. Much like my analogy of conceptual space, we cherry-pick the theory that we want to present in practice.

Morning Mood Analysis: How Grieg Turns One Idea into Endless Music A Composer’s Guide to Morning Mood Analysis Edvard Grieg’s “Morning Mood” …

This article explains how to orchestrate a melody by reducing orchestration to six fundamental approaches, helping composers make clearer and more deliberate decisions.

O Little Town of Bethlehem looks simple on the page, but it isn’t simplistic. In this analysis of the Forest Green version, I explore how Vaughan Williams creates shape, contrast, and finality using a remarkably restrained harmonic palette, showing how small details in form, cadence, and line carry real expressive weight.

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …