I am not a great reader. Not in the sense of my comprehension. Rather, my focus and concentration are poor, particularly when reading books on music composiation where my capacity to comprehend the contents, ironically, is much higher. As a result, my ability to get through such books or articles is diminished. The reason for this is these kinds of books tend to send me down rabbit holes of thought and imagination. The mentioning of a technique or concept starts me thinking about how I could use that technique or concept creatively. By the time I have come around from my daze, I have progressed by several paragraphs or pages and my lack of focus leads me to lose the writer’s train of thought and explanation. I then have to backpedal to the point where I lost my focus, regather my understanding and reread.

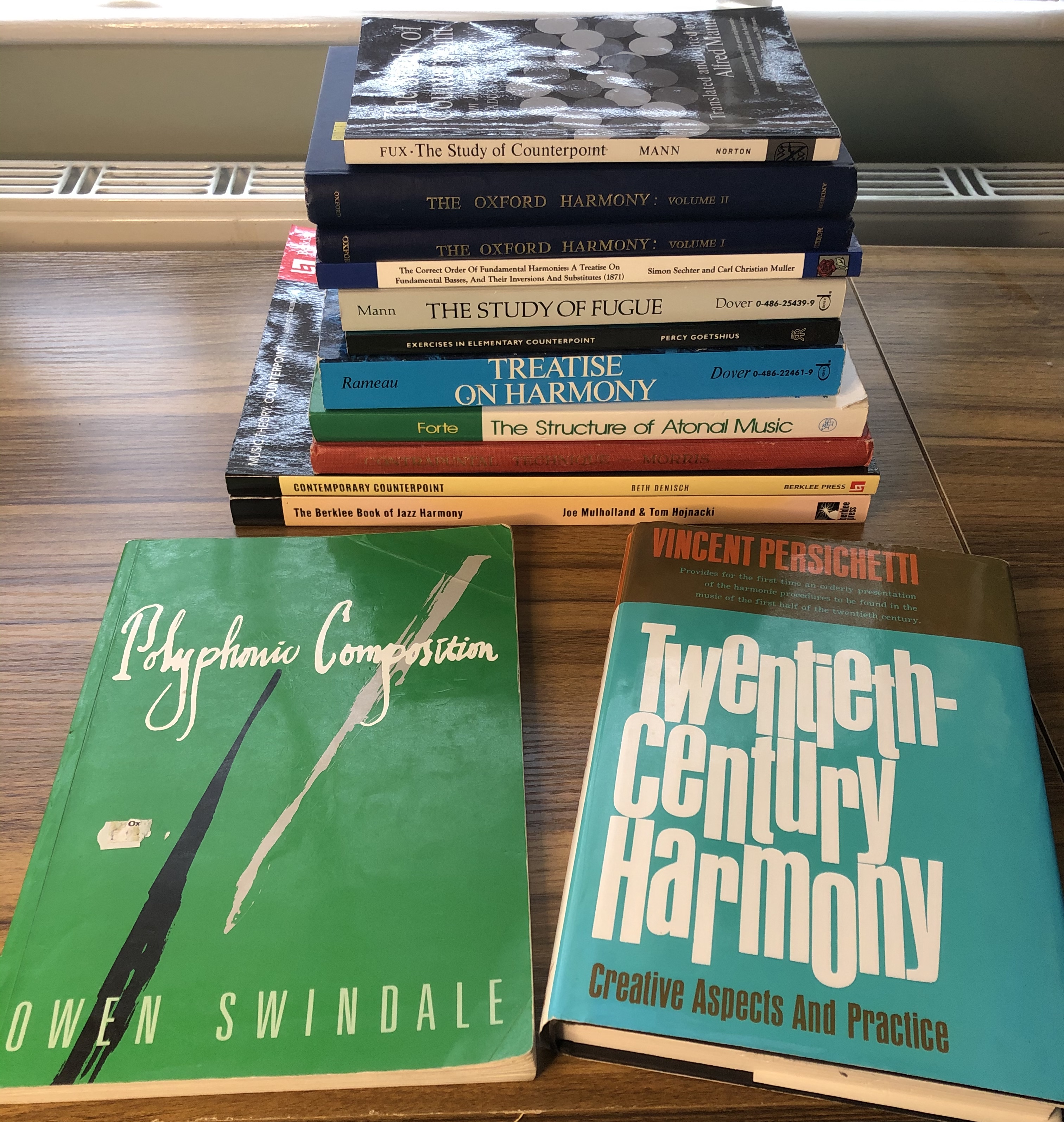

Despite this steady approach to reading, I have developed a modest library of music books. I thought, therefore, it could be interesting to ask and answer the question: what books would I keep above all others? If I were exiled (for crimes against music), what Five music books would I take with me?

The books I have chosen, from my humble personal library, are predominantly related to music composition. I suppose it says something, not only about myself, but about the innate fulfilment studying music composition (or different arts, or fields of knowledge, for somebody else) provides. Even in exile and, possibly, isolation, I feel that I will still have both a compulsion and satisfaction for learning and writing music.

*None of the links I give in this article are affiliated.

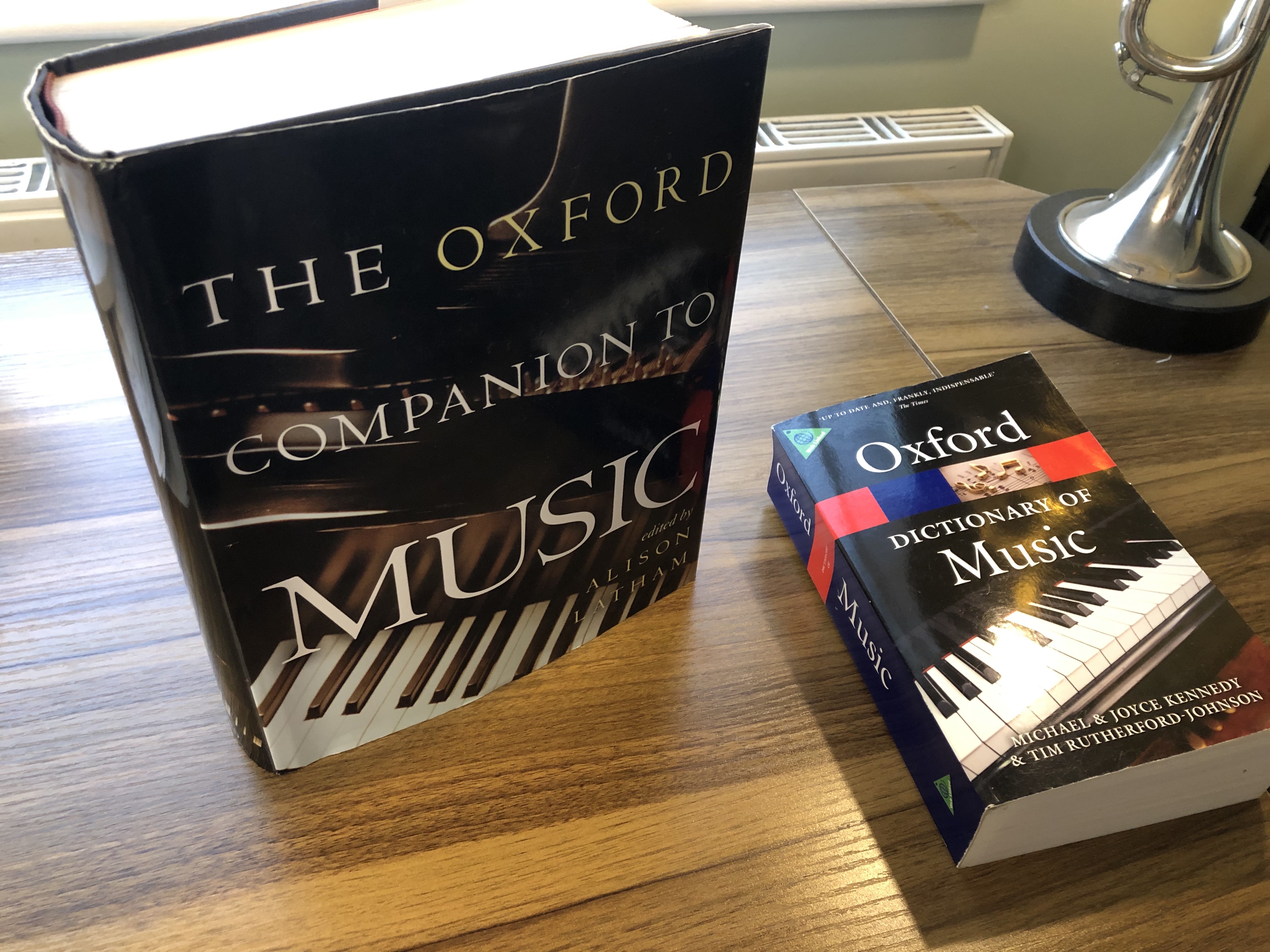

1. The Oxford Companion to Music

This first book, The Oxford Companion to Music, might seem a strange one. And, to be honest, it is not a book I think I would have brought myself but is one that I absolutely cherish now. I was given it as a 21st Birthday gift, and it’s just a fabulous reference book. Even now, (perhaps even more so) with the likes of Google, where I can find things out with ease, the companion is one of the first places I’ll turn to for an answer. Therefore, it is also the first one I’d put in my survival pack.

There is something to be said about a definition set in print as opposed to being online. It could be purely psychological, but knowing the author will not have the option to edit the text gives it more authority. The author and editor are less likely to want to put their name to something if they have not, at least, gathered sources to support their definitions, whether those sources are cited or not. (Practiced only for direct quotation in these kinds of books.)

I have the Oxford Dictionary of Music, which is also a good reference for things, but the companion is a bit bigger, covering a wider range of things. For example, it has some nice “feature sections” on composers and certain important periods, styles or concepts. I could turn to ‘B’ and get a big section on “Bach”. Or, ‘O’ and read up on Opera. What I like about this style of reference book is that it cannot afford to be loquacious. It has to drill down and be selective, and I find that interesting too: what it chooses to leave out and pick out.

Although the book does cover universal concepts, such as “acoustics”, it focuses on important figures and styles in Western music. The two examples I gave before, for example, are titanic parts of the Western music tradition: “Bach” and “Opera”. My only criticism, therefore, which garners a lot of debate within music and educational institutions at the moment, is that it ought to specify that it focuses on Western music in some way or another. A modern edition ought to specify that in its title: The Oxford Companion to Western Music, perhaps? Or, possibly, The Oxford Companion to Western Classical/Art Music. Although, I am not fond of the words “classical” or “art” as terms for defining the music that I mean here. Art suggests superiority to popular idioms and classical also has a specific meaning within music too. Using it discounts music before it. However, there does need to be a way of specifying its focus.

If you’re enjoying this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

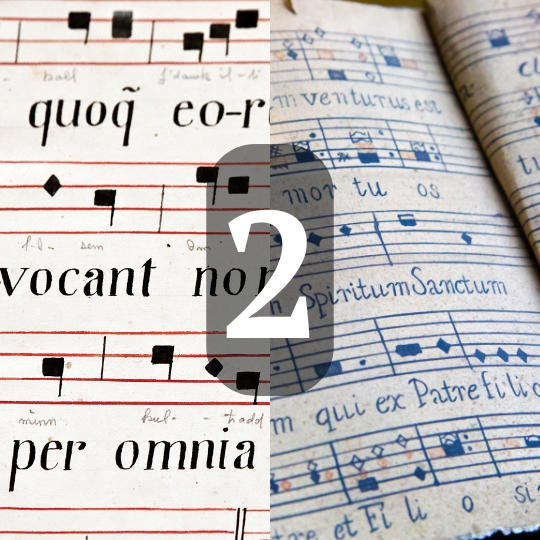

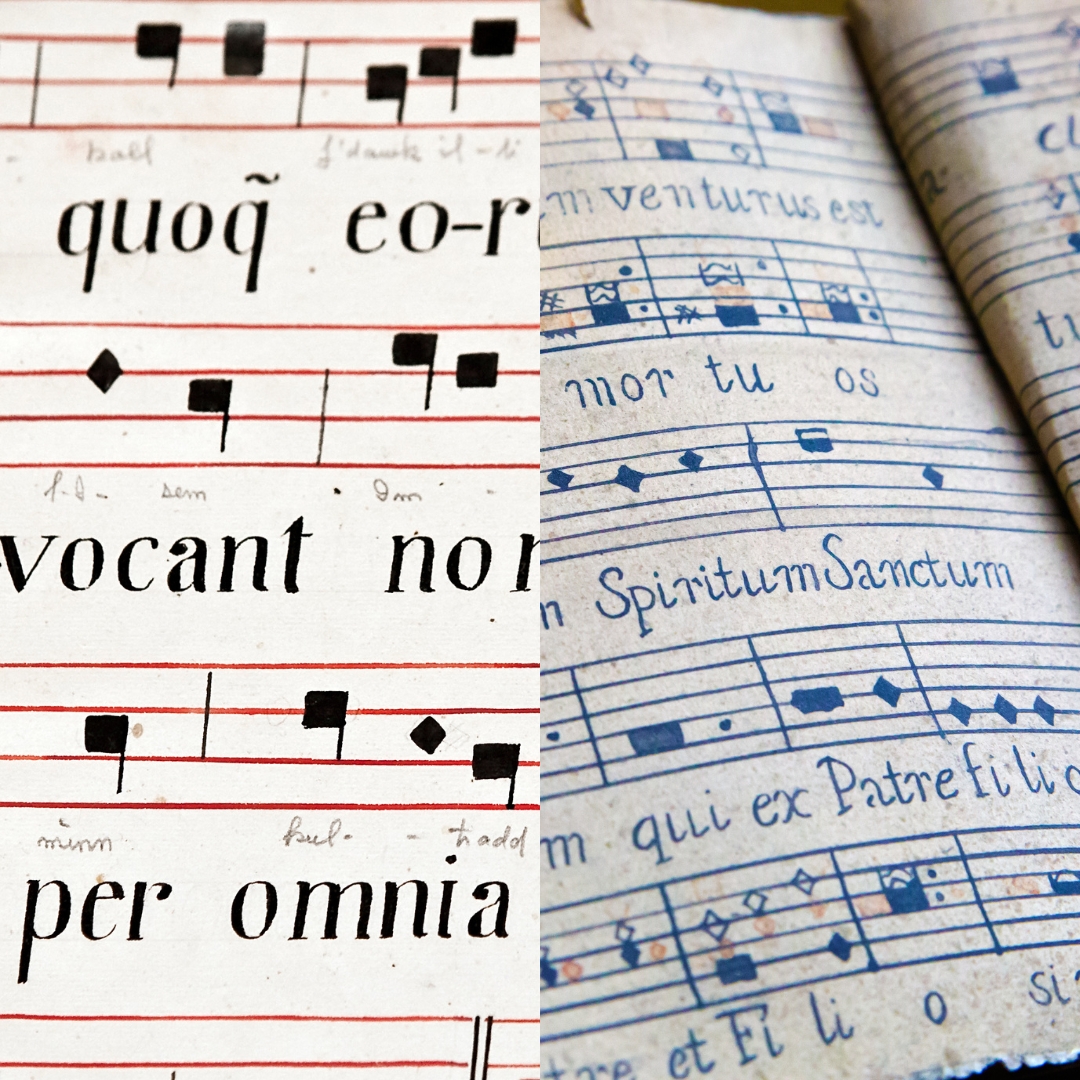

2. Polyphonic Composition (Swindale)

My second book is a counterpoint book called Polyphonic Composition (1962) by Owen Swindale. I figured I might have time to kill, in exile, and might like to revisit my counterpoint studies. (I probably should!) I predominantly self-studied counterpoint at University and have revisited it several times. I particularly enjoyed the 2-part counterpoint as I felt it was the most useful. Whereas the addition of voices seemed to bring with it issues that were not salient to the music I wanted to write. Maybe I was wrong, and this is not to say in my earlier studies that I did not persevere. However, in subsequent visits, I tended to revise and practice only two-part counterpoint.

I have many books on counterpoint. This one is, by far, my favourite and the one I found the easiest to get through when studying my self. I found it easier to comprehend than Gradus ad Parnassum and, despite being an older manual, nicely laid out. One thing I find with older texts is that they can seem like walls of text. Possibly as a limitation of older print methodologies? However, this one is concise and uses well engraved and labelled examples.

Norman Del Mar’s engaging and informative writing provides unique insights into instrumentation and the lived experience of a knowledgeable conductor and horn

3. Twentieth-Century Harmony (Persichetti)

The third book that I would take with me is on the topic of harmony. It is called Twentieth-Century Harmony (1961) by Vincent Persichetti. Similar to how I found three or more voices of counterpoint study to be less readily applicable, I never found a harmony book that inspired or influenced what I wanted to compose.

Where I could easily mould two-part counterpoint into sounds and directions that I wanted to go, Persichetti’s book is similar. Most harmony books taught concepts related to functional harmonic procedures, which typically resulted in pastiche or explicitly harmonic, homophonic composition. That was fine, in of itself, as exercises. However, translating that knowledge creatively, for me, was difficult.

The closest “practical” manual I came across before the Persichetti was Simon Sechter’s 19th-century text, The Correct Order of Fundamental Harmonies: A Treatise on Fundamental Basses, and their inversions and substitutes (1871) (Still here?). However, it just extended 18th-century (“common”) practice into 19th-century practice. Therefore, it is good if you want to understand that, Romantic language more. As a composer, I was after this, to a certain extent. However, I also wanted a combination of different harmonic structures, interactions, voicings and relationships too. (Which I am still working on!)

I like the Persichetti as it is less prescriptive and restrictive, more suggestive. Furthermore, many of the harmonic devices and concepts it discusses are not outdated. Or, if they are, they are not too far detached. It simply lists and describes concepts, beautifully concisely, as if to say: “There you go. Do what you will.”

Another great thing that I like about this book is that it suggests exercises and extensive lists of examples so that, if you can access the scores, you can see the harmonic device he is discussing in practice. Giving you more things to study and deepen your understanding. In exile, I might be able to explore all the things it puts forward… Exile is starting to sound like paradise.

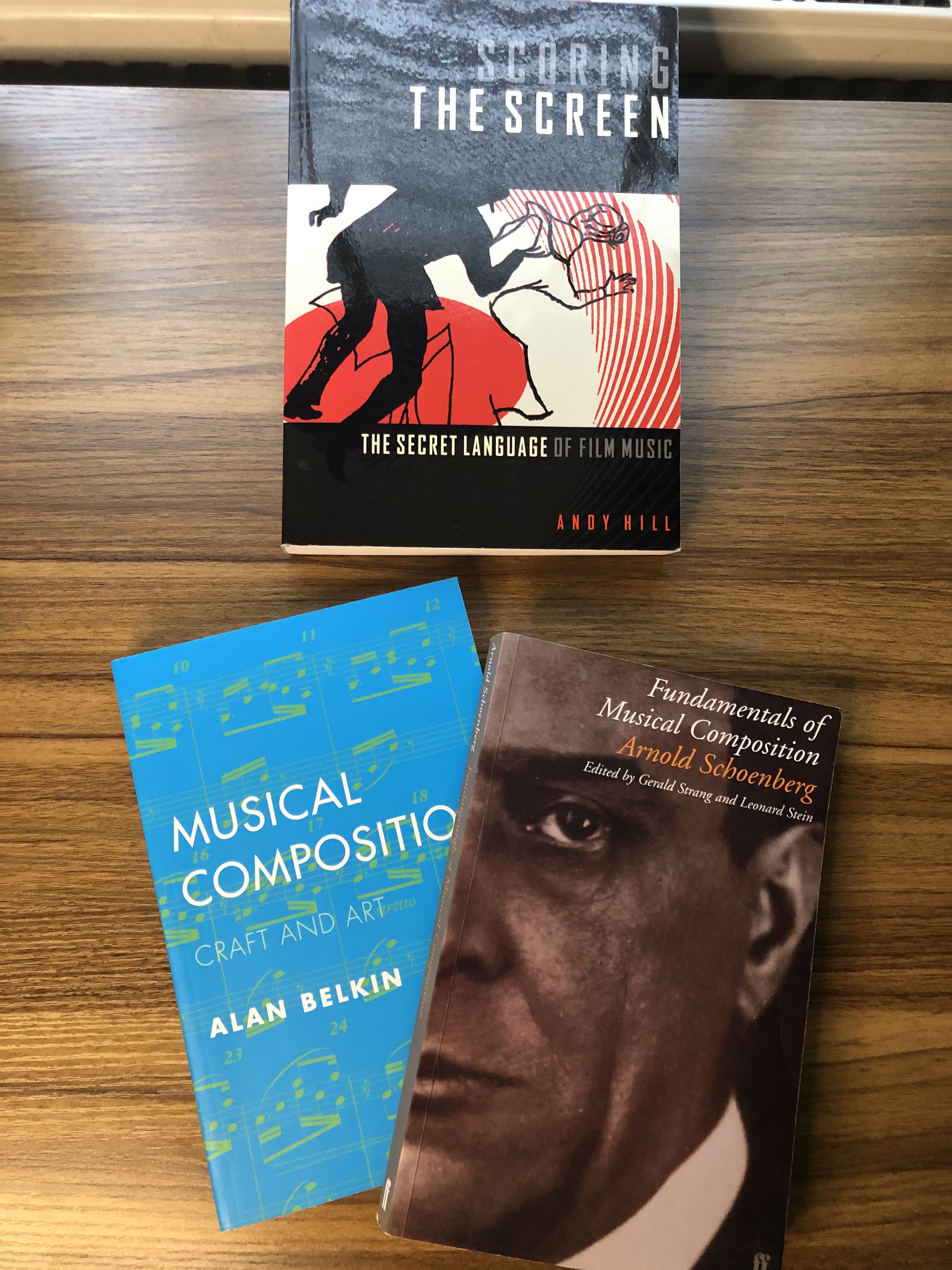

4. Fundamentals of Musical Composition (Schoenberg)

The fourth book I would take with me is Arnold Schoenberg’s Fundamentals of Music Composition (1967). I like this book as it discusses composition techniques in a way that I engage with composition. I am not particularly good at playing instruments, so I generally rely on theory, concepts and engaging with music cerebrally. Schoenberg, therefore, gives me the vocabulary with which to think about music more objectively and, to an extent, universally.

Similar to the Persichetti, it gives extensive examples and prints short extracts of these examples in the book. Therefore, you can see the concepts that he is discussing.

Another similar book that I have and like is Alan Belkin’s Musical Composition. I think it may have been on the list if I had been a younger student when it was published. The progression for me is Belkin then Schoenberg, which is not to do with the complexity of information. Rather, Belkin’s is more accessible in its delivery. In this sense, I would probably recommend it first. However, thinking of my self in exile, Schoenberg gets into the language that I find myself turning to more and more.

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes

5. Scoring the Screen: the Secret Language of Film Music (Hill)

The fifth one may be surprising as it is not another manual (the glaring hole being, Orchestration), but a book on film music: Scoring the Screen: the secret language of film music (2017). It’s probably because this one is not a manual that I chose it above The Study of Orchestration.

I love this book as it’s a digestible series of analyses on film music composition. Usually, each chapter is based around something specific, branching out from that area. However, it does also step back and look more widely at the field. For example, Chapter 1 looks at Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo, but in doing so, identifies consistencies in Herrmann’s other scores. Whereas Chapter 3 looks at signs and meaning that has developed around the use of certain musical language. It could not dream of being comprehensive in such a big and neglected field, but it has plenty of great observations. This is one of those books that sends my imagination spiralling and, therefore, being in exile might let me get through it with more discipline!

Summary

It is an interesting exercise to think about what music books I would keep if I had to get rid of most of them. I certainly have not read all the books I own or read many from cover to cover. Then again, I tend to learn more through extracting a single concept that I can then attempt to put into practice. As a result, it does take me ages and an intense amount of discipline to get through those valuable books, which enable that approach. Exile on a desert island might give me that time and focus?

If you’ve enjoyed this article, why not sign up to our musical knowledge bombing list? (Find out more by clicking the link. Thank you.)

Musical Moments is a new series where I focus on larger works—whether in orchestration, length, or complexity—and zoom in on small sections …

Fourth Species Counterpoint is a type of music composition that focuses on creating counterpoint through suspension and syncopation, which means that notes …

Combining 1st and 2nd species counterpoint is where we truly start to unlock counterpoint’s potential as a tool for enhancing our composition …

Continuing from the foundational work in first and second species, third species counterpoint introduces a more intricate rhythmic structure by pairing four …

Continuing our study of species counterpoint from last week, where we looked at counterpoint in the first order / first species, this …

First species counterpoint, often referred to as “note against note” counterpoint, is the foundation of contrapuntal composition. It (First Species Counterpoint) involves …