The orchestral composition Farandole, a movement from Georges Bizet’s L’Arlesienne Suite No. 2, can teach us a lot of simple tips and tricks that we can apply to our arrangements, compositions and orchestrations. In this article, I analyse the piece and discuss its structure, its clever use of simple themes, textures and orchestration. For example, one simple but exhilarating technique this composition/arrangement uses is to counterpoint its themes at the end (see Themes/Melodic Material)

Master the Art of Horrifying Orchestration

Join us and develop the skills to scare your listeners.

Use coupon code scar3yd15count for £50 off!

Context/Background

L’Arlesienne, or the “Woman from Arles”, was originally a play produced in 1872. It was adapted from an 1868 novel by the author Alphonse Daudet. Bizet was commissioned to write the incidental music for the play and actually performed the Harmonium part in the premiere performance. Despite the poor reception of the play, which received only 21 runs. Bizet went on to arrange the first concert suite that same year, and since then the music became and has remained popular in orchestral concert programmes. The second concert suite was arranged seven years later in 1879, four years after Bizet’s death. Unsurprisingly, this arrangement was not created by Bizet, but by his friend and fellow, contemporary composer Ernest Guiraud.

Recording/Score Videos

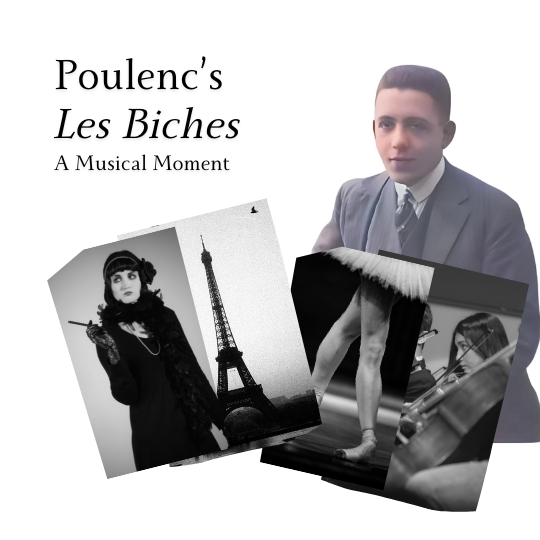

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

The Orchestra

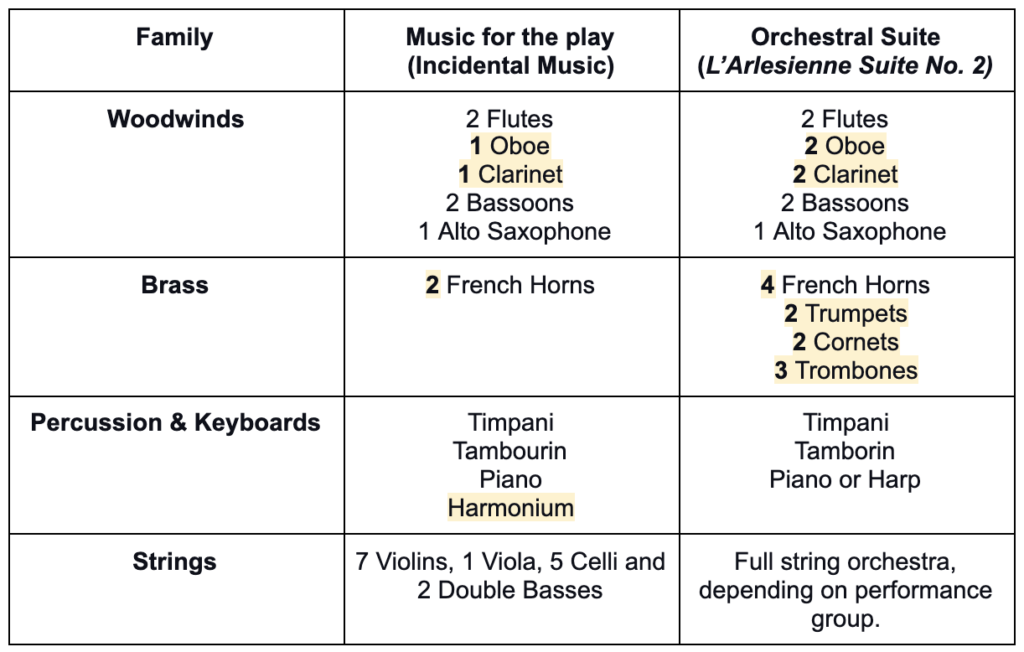

The original play, according to Wikipedia–reliable, I know–had a much more modest contingent of players than the later arrangements that are for full orchestra. I presume this was a budgetary decision, no different to live performance or recording today. Bizet will have likely needed to strike a balance between what he needed for his music and what budgets would allow for running the whole production.

On the table below, it is easy to see the differences between the orchestra for the incidental music and the orchestra for the second suite. The original orchestra had a specified number of strings, only two brass players in the form of French Horns and then a group of six Woodwind players. In arranging the second orchestral suite, the brass section is increased in size dramatically. The harmonium is dropped, woodwinds are doubled throughout, there is the notable addition of a saxophone, which does not play during Farandole, and extra interestingly the piano becomes interchangeable with a harp.

The table above shows the difference between the two orchestra’s of the original composition and the arrangement of the suite. The Brass section is much larger in the suite.

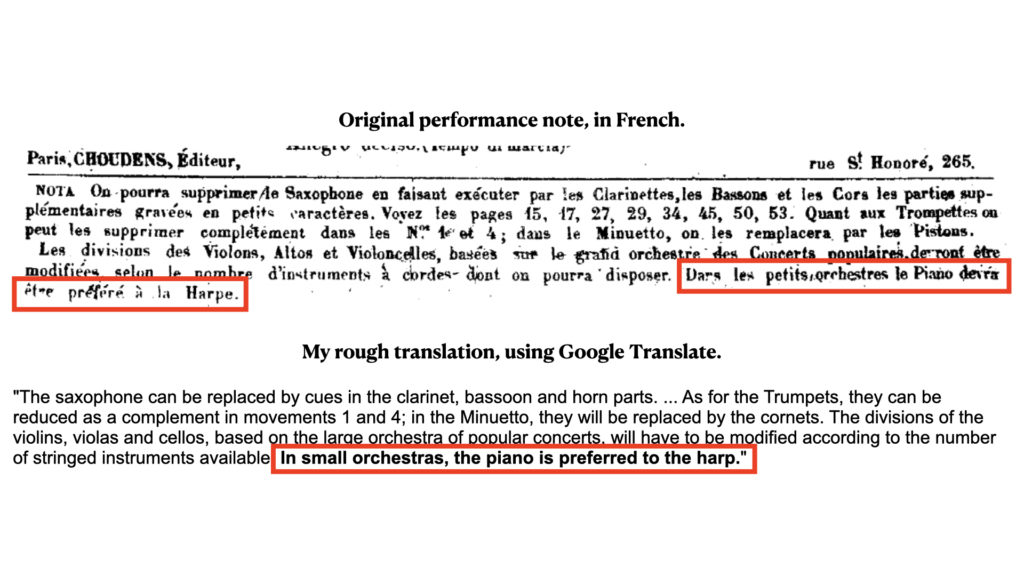

The interchangeability of the harp and piano is explained in a concert note at the bottom of the first orchestral suite, which states that the piano is suggested for orchestras with smaller string sections. Presumably, as we can see in the harp part, for the first movement of the first suite, this is so the piano can cue and support important lines in the string orchestra. Stronger dynamically than a harp, if a smaller string section needed some support in a performance, the piano, through playing those cues, can provide it.

A performance note from the first L’Arlesienne concert suite, a similar shorter one exists on the second suite. Interesting, it demonstrates considerations and flexible, realistic approaches to orchestration that increase the accessibility of arrangements for various orchestras, professional and amateur, to perform.

The same performance note, from the first suite, explains the use of music cues, particularly for the saxophone. An instrument that was in its infancy during this period, it was an orchestral guest and, sadly, remains one. Therefore, having a score and parts that can cover the absence of certain instruments as the saxophone or, possibly, lower chairs, makes the music more accessible.

The second suite has a similar, shorter performance note, which together, along with the addition of cued parts, shines a pragmatic light onto attitudes toward arranging, orchestration and performance of this time. Offering flexibility in instrumentation, through cues and suggestions for suitable alternatives, will mean more orchestras can programme the music, a lesson we can certainly still heed today as composers, orchestrators and arrangers.

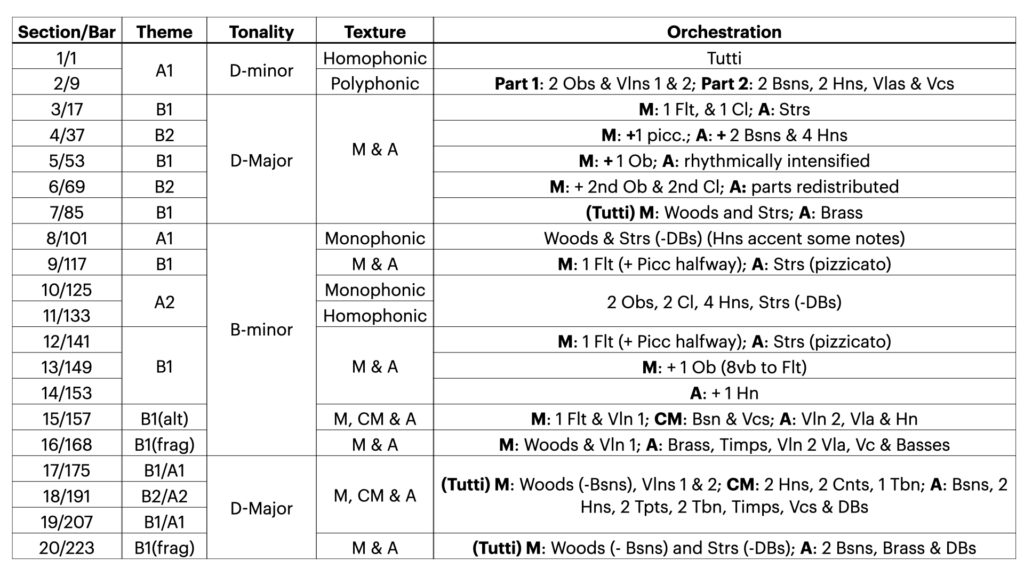

Orchestration & Texture

The orchestration and arrangement of Farandole is gracefully simple. Guiraud communicates the sectional structure of the work by making switches of texture, along with simple additive and subtractive orchestration: increasing or taking players away at the beginning and end of sections. This additive process is best demonstrated by the passage from section 3, bar 17 through to the beginning of section 8, bar 85. Through this part of the movement the orchestra builds gradually, going from a single flute and clarinet combination, accompanied by strings, through to an orchestral tutti that sees the Brass accompany a Woodwind and String melody in octaves.

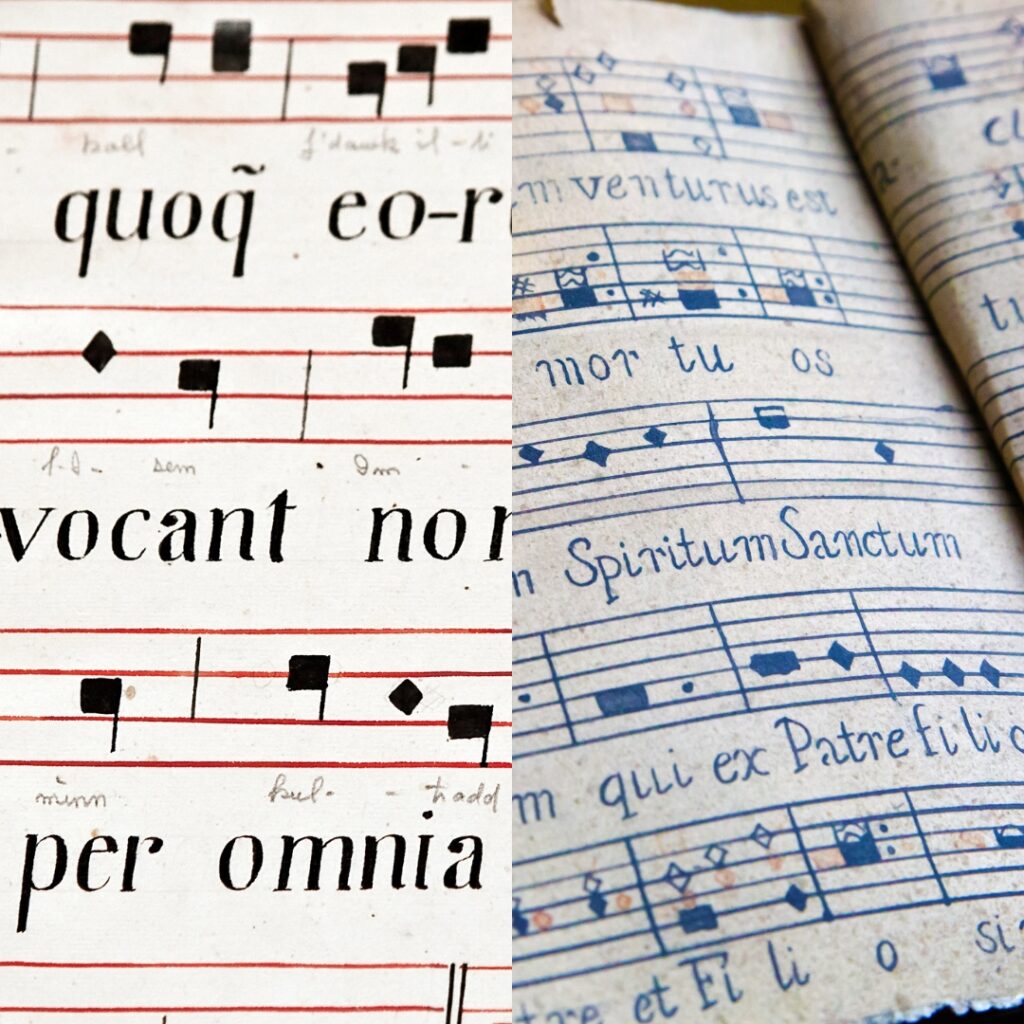

Considering texture, we can begin to see how Guiraud can get even more interest out of the material. Melody and accompaniment, with the addition of counter-melody in the final section, is the primary texture of the work. For variation, he also uses other textures. Homophony, where voices move together to produce a chordal, hymnal texture, is used in the opening and middle section of the work. Polyphony follows this, in the form of a two-part canon, during the introduction of Farandole.

Polyphony distinguishes itself from homophony by elevating melody. For example, if you were to extract each line from a polyphonic texture it should have melodic interest on its own as a monophonic texture. In the case of the canon, the same melody is played against itself but offset. The harmony in a canon, therefore, emerges from the linear unfolding of these two melodies against one another. Monophony, which appears in the middle section of Farandole, is a line played on its own in unison or octaves.

Tonal Scheme

The melodic material in Farandole is scarce and motivic developments modest, with only a couple of periods within the piece where the melody is subjected to any motivic changes. The main developments occur in large-scale changes to the themes via transposition into different tonalities and modes.

If we first add in the tonal scheme of the work, we can see the tonal areas explored are compact, with clear relationships between each of the tonal changes. Each modulation can be defined as parallel or relative. For instance, D-major is the prevailing key of the work, but the work opens in the parallel D-minor. In the middle section, we move to the relative minor, B-minor, before returning to D-major to close the piece. These closely knit tonalities give the work a structural balance between variety and expansiveness.

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Themes/Melodic Material

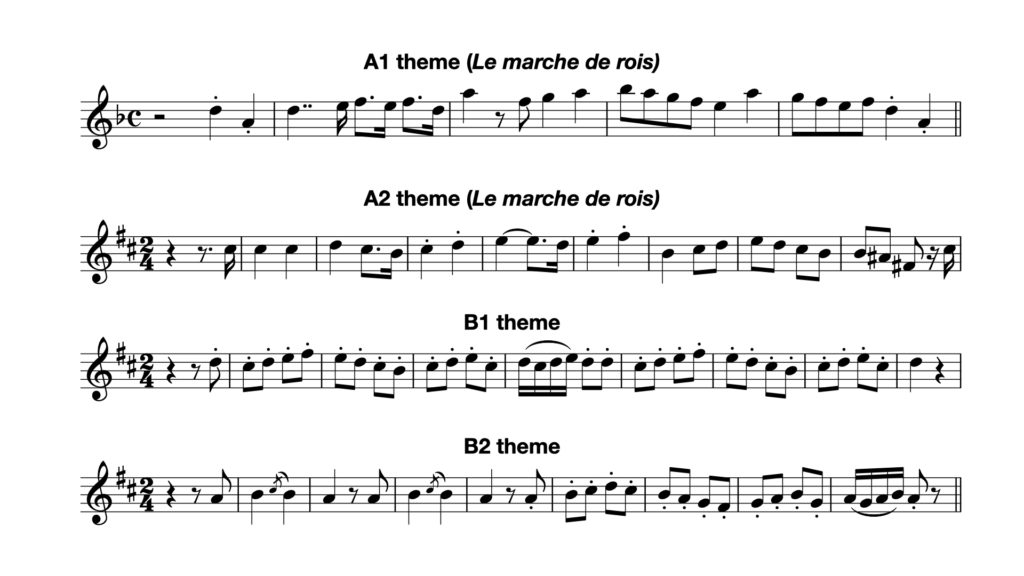

Melodically, the work presents four 16-bar melodies, each made up by two, similar, 8-bar sentences. Despite being juxtaposed in the first two-thirds of the work, in a way that makes them seem unrelated, the opposite is true. Each one of the four melodies is related to two others: one linearly and one contrapuntally. To outline these relationships, I label the themes, A1, A2, B1 and B2. The letters to signify linear relationship and the number to signify contrapuntal relationship.

The 4 themes extracted from Farandole. Exposed gradually through the movement, the A1 and B1 themes, then the A2 and B2 themes are placed in counterpoint with each other close to the end of the movement.

The A1 theme is the theme many of us attribute to L’Arlesienne as it also appears in the opening prelude that Bizet arranged in the first suite. Guiraud may reprise the melody here because of its use in the first movement: Western Music of this time had a fondness for recapitulation. Furthermore, it is not uncommon for orchestras to programme the two suites together. Impossible to predict it is not implausible to think recapitulation and dual programming, of the first and second suite, could have been a consideration in Guiraud’s process of arranging the second suite.

Both the A1 and A2 melodies are from a carol called Le Marche de Rois. (I see la and le… I am not sure which is correct, being terribly monolingual.) In this carol, the A2 theme is the second sentence in a larger theme, which Bizet also exposes in full in the Prelude of the first suite. However, in Farandole, Guiraud exposes the A2 melody midway through the movement, breaking the carol into two. The knowledge that this is a traditional French melody, likely well-known by French music goers of the time, changes the whole complexion of the movement. Guiraud denies expectations, creating a form of melodic dissonance that is not resolved until the final section of the movement when the themes linearly unfold together.

Two compositions that use the melody Le marche de Rois.

The B1 and B2 themes are what characterise this work as a Farandole. Light, they capture the dance-like quality of a Farandole, which is

a traditional dance

in Provencal France.

(poetry.)

Having not been able to access performance, I would be interested to know how the themes operate in the play narratively and musically. The use of the pre-existing melody and the Farandole, I imagine, are used to reinforce the setting. Arles, being a city in Provencal France, has a strong cultural identity as part of this wider region, which the Farandole belongs.

The B1 and B2 themes linear relationship is clearer. Following the truncated A1 exposition in D-minor, both melodies are repeated many times. It is the order and multitude of these repetitions that their linear relationship is veiled, making each melody seem like its own whole. It is only in the final section that their linearity is asserted, through their relationship with the A1 and A2 themes.

In the final section, the second relationship between the melodies emerges. The numbers of my labels distinguish, not only linear order but counter-melodic relationships: the A1 theme counterpoints B1 and A2 with B2. The effect is strident, made dramatically poignant by the return of D-major and the transposition of the A themes into a major mode. Furthermore, the hearing of all the material in full form, together, adds to this effect.

There is an irony here with regards to effect and musical description. Despite being in actual counterpoint, the sense of conflict brought about by the sectional juxtapositions earlier in the movement is resolved by what we think of as a texture defined as “point against point” and not “point together with point”. Then, I suppose, polyphony is an inherently egalitarian texture. Each line is independent; each line is important.

Conclusion

A short movement, particularly by 19th century standards, there is a lot for us music makers to learn from Farandole. Economical, it demonstrates that you do not need a great deal of complexity to create something for an orchestra that is compelling. Instead, you can use the orchestra itself as a device for variation through colour, texture and dynamic versatility. Furthermore, if you have one melody, why not use it as the foundation for a second one, creating a counter-melody that you can then expose on its own earlier in the movement? You could then just transpose those melodies into closely related keys, for variation? Control the complexity of your work, to meet the time, inspiration and motivation you have.

Video Version of Article

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Sources (with links, where relevant)

Bizet, G. (1873) L’Arlésienne Suite No. 1 [Musical Score]. Paris: Choudens Père et Fils.

Britannica (2020) Farandole: dance.

Britannica (2020) L’Arlésienne: incidental music.

Dahlhaus, C. (1989) Nineteenth-Century Music. Translated from German by J. B. Robinson.London: University of California Press.

Grove Music Online (2001) Bizet, Georges (Alexandre-César-Léopold).

Grove Music Online (2001) Farandole.

Grove Music Online (2001) Guiraud, Ernest.

Latham, A. (ed.) (2002) The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wikipedia (2020) La marche des rois.

1 thought on “Bizet’s Farandole (L’Arlesienne No.2): music composition techniques”

Comments are closed.

Pingback: The Flag Parade - Music Composition Techniques - Any Old Music