Chopin’s Nocturne No. 19 in E-minor (Op. 72, No. 1) was published posthumously as part of a larger collection of works in 1855. However, its thought the composition year was about 3 decades earlier, in 1826. This date places the Nocturne early into Chopin’s career as a composer. So early in fact that he was still studying in Warsaw at either the Warsaw Lyceum, essentially a UK-secondary or US-high-school level educational institution. Though it is possible that he may have just started at the Warsaw Conservatory. Therefore, Chopin would have been about 16, possibly 15, years of age when this piece was written.

Assuming this is the correct year of composition, Nocturne No. 19 is a remarkable composition for a young student, and there are qualities to this nocturne that make it seem very much like a student composition: simple, in-expansive formal arrangement; clear use of harmony, with overt part writing techniques; and a concise use of melody, with melodic development limited to ornamental variations and embellishment. As if to demonstrate an understanding of different techniques, Chopin was clearly a student dedicated to developing his craft as a composer.

In this article, I want to unpack several observations regarding arrangement and form, harmony, and melody. We will start first by breaking down the form into its components. We will then look at harmony, predominantly the use of techniques that allow for a richer harmonic variety, and then melody. A technique that Chopin would go on to use in later works, we will observe how Chopin uses melody and variation as a lynchpin of form.

Form

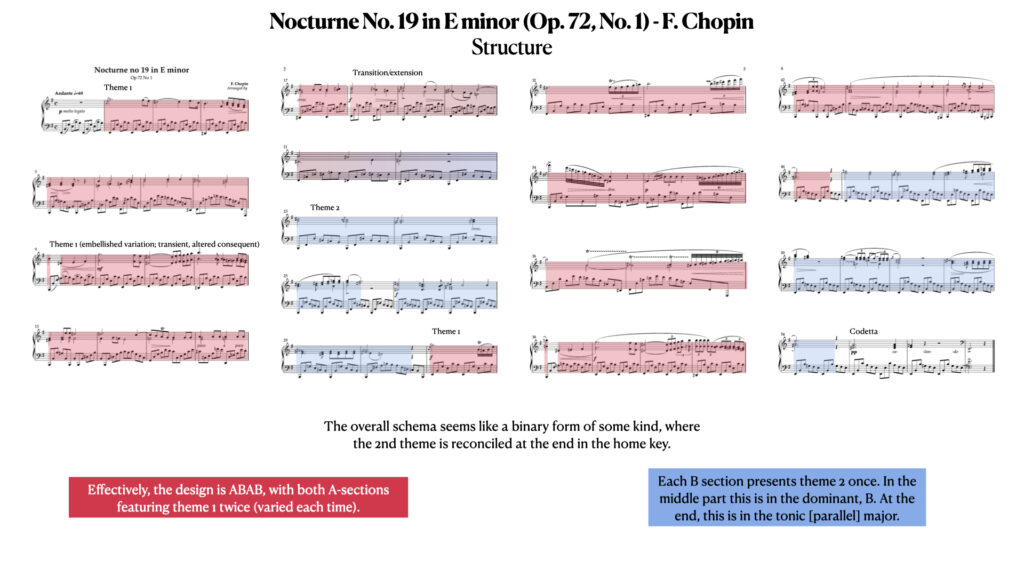

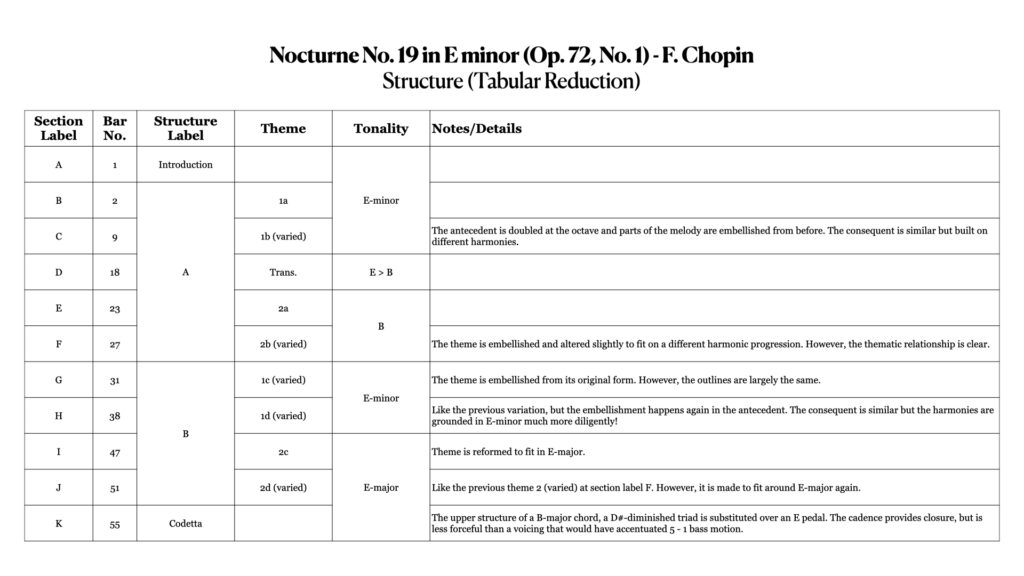

The form of Chopin’s Nocturne No. 19 is straightforward, and could be said to follow a rule of 2:

- There are two themes (Theme 1 & 2)

- These themes are each presented twice, with an immediate and varied repetition following an initial statement (Theme 1a & 1b; Theme 2a & 2b);

- These pairs of themes are repeated with further variation, in new keys (Theme 1c & 1d: E-minor; Theme 2c & 2d: E-major), in the second half of the work.

Things happen in pairs. And, in part because of this, if I were to ascribe a label to the form of this piece, I would be inclined to say Binary Form. However, there are a couple of things that call this into question, such as the modulations and use of a transitional section. Typically, traditional binary forms use the same thematic material across two parts. There tends to be a reforming and weaving of the same thematic material through a broader modulatory schema that often goes from tonic (I) to dominant (V, or the relative major, III) in the first half, and then back again.

Chopin does the first part of this binary form plan. The piece starts in E-minor (i) and moves to B-major (V). However, when theme 1(c) returns, so too does the tonic key. Ending the piece with theme 2c and 2d, there is a further modulation to the parallel major, E-major.

We could, therefore, label the form—if we really need to—as strophic, thinking of it as A-A’ rather than a binary, A-B. There are pretty neat repetitions of the themes, not too dissimilar to—though much smaller than—classical variation form, where the piece builds on the same structure (the theme), creating variations and permutations. Internally, the theme might have multiple parts, but on a larger scale the pieces are built on the framework of that structure. Chopin gives us theme 1a, 1b, 2a and 2b, which could be seen as A. He then repeats the process, giving us theme 1c, 1d, 2c and 2d, each variations on the same themes, in the same structural order, which could be read as A’.

Cross fertilisation

Beyond binary and strophic forms, there are elements of ternary form in this piece. Theme 1 is recapitulated, but so is theme 2. Generally, in a ternary form only one theme would be recapitulated.

The reference I make to ternary form here is its growing popularity as a form in the 19th century. Where a Binary form is often built around a process of exercising a or multiple small ideas around harmonic and modulatory structures, Ternary form is about larger ideas that contrast. While harmony is often paralleled with these contrasts, modulating to a new tonal area for a new theme, the emphasis is on melody. Before the 19th century, where Binary forms are more prevalent, the emphasis was on harmony: building from the bass upwards. This Chopin nocturne is built around melody: from the top down.

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

Harmony

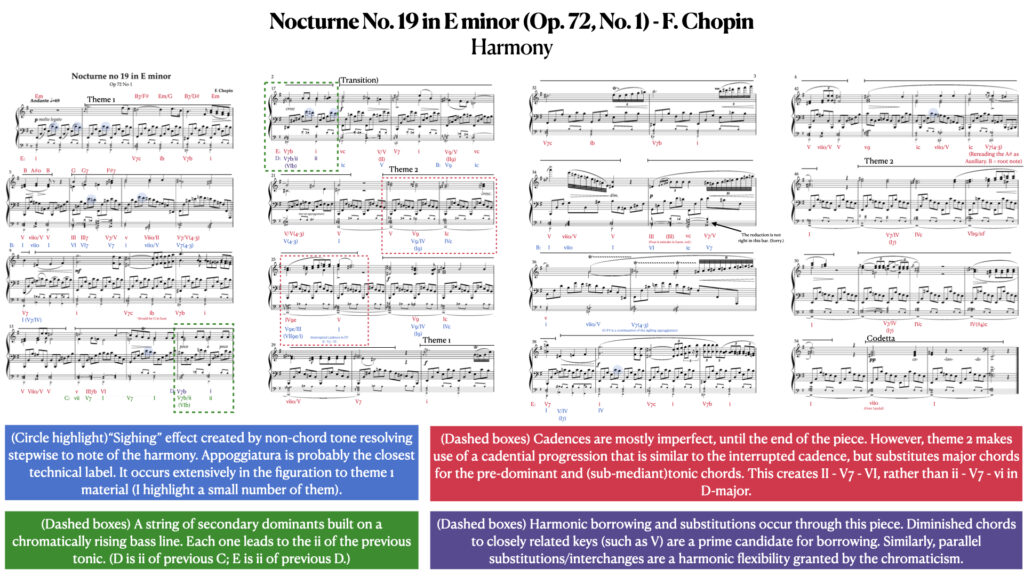

Harmonically the language is tonal and functional. One can apply roman numerals to every ounce of the composition. Therefore, while I will look at a handful of extracts shortly, I want to turn our attention to the various “non-chord tone” techniques that Chopin uses in this piece, such as appoggiatura, “sighing” resolutions and suspensions.

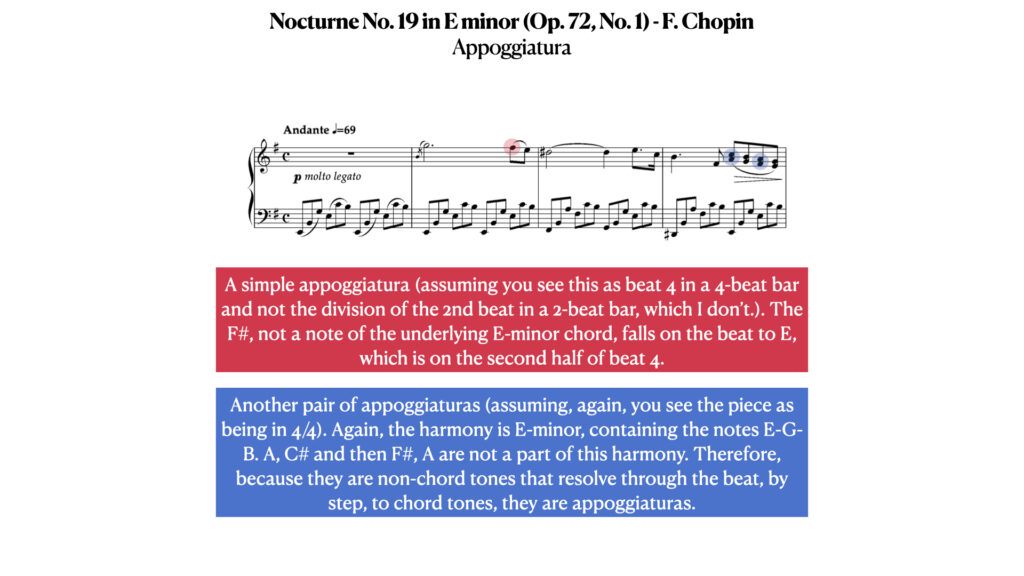

Appoggiatura

A frequently used technique in this composition is the appoggiatura. The appoggiatura is a technique that uses non-chord tones, a note or notes that are not a part of the underlying harmony, on a strong beat of the bar. These then resolve by step onto chord tones: notes that are in the underlying harmony. For example, in the opening of theme 1s exposition (bar 2-5), we can see several appoggiatura. The first bar of the melody for example uses one on beat 4, falling from F# to E, above an E-minor triad. F# is not a note of a simple E-minor triad. In bar 3 of the melody we see a pair of appoggiaturas on beats 3 and 4. Above an E-minor triad, again, the notes A and C (beat 3), and F# and A (beat 4) are non-chord tones. Resolving by step to G and B and E and G, respectively, a pair of appoggiaturas are diligently deployed by Chopin in this bar.

IMAGE SLIDE 4 – APPOGGIATURA

Appoggiatura mach 2(?): Sighing Resolutions

Depending on the strictness of your definitions, Chopin uses an appoggiatura like figure persistently in the left hand. Distinguishing sections, Chopin pairs his themes with a distinct, repeating figure in the left hand of his Nocturne. Under theme 1, these figures include a non-chord tone on every 2nd and 4th beat of the bar. Already the weaker beats, per se, the non-chord tone also appears on an “irrational” 2 of 3 triplet division within the beat. Not accented, therefore, the Appoggiatura nomenclature is debatable. However, it does possess a trademark “sighing” or tension-release feeling that is similar to appoggiatura.

Looking at the appoggiatura extract again, I have highlighted the repeating C-B figure in the left hand. C, a non-chord tone of the underlying E-minor chord, resolves to B. Appearing persistently, Chopin nearly always uses an added 6th to the underlying harmony that resolves to the 5th of the chord. For example, in the second part of theme 1, the harmony begins to move away from E-minor chords. Each time the “sighing” motif, in the accompanying figuration, occurs again and again between the 6th and 5th of the underlying harmony.

IMAGE SLIDE 5 – “SIGHING”

Suspensions

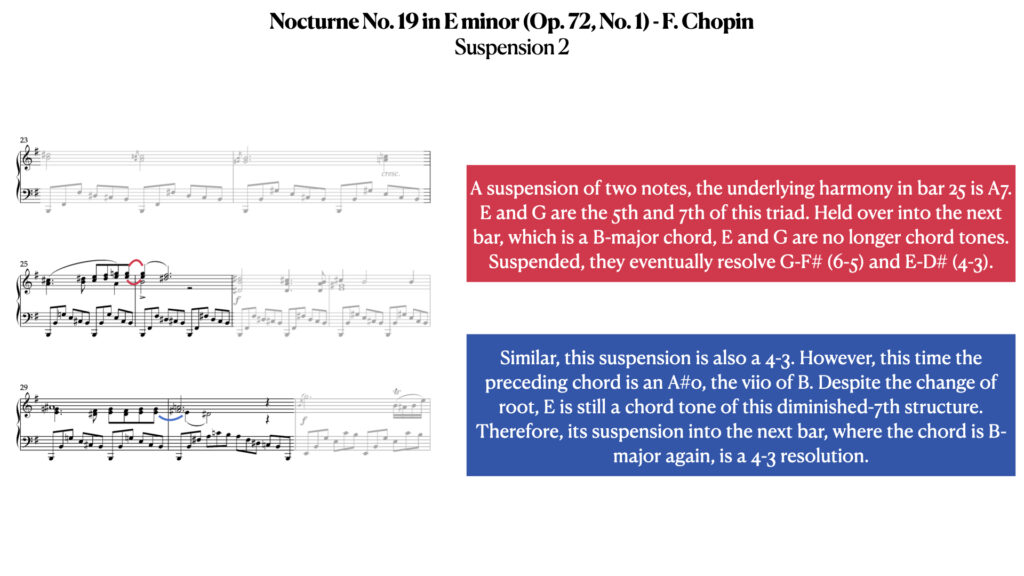

Another technique that Chopin uses, perhaps more frequently than appoggiatura even—especially if you exclude the “sighing” motif—is suspension.

Using traditional prepared suspensions, where the non-chord tone exists in the preceding harmony, Chopin usually does not tie the non-chord tone over from the previous beat. Instead, accentuating the dissonance—as the piano is a non-sustaining instrument—the non-chord tone is often replayed.

Typically, in classical music a suspension is a tied note from the previous chord. However, why might Chopin not do that here, in his Nocturne for piano? Why might he replay the note? Well, my assumption is that its because it is for the piano, which is a non-sustaining instrument. Therefore, after the initial attack, the piano’s volume is decaying. This means that a suspended dissonance is losing its potency. Chopin wants us to hear the suspended dissonance, which is also why he often placed these suspensions in the upper-voices as a 2nd interval.

A frequent suspension that Chopin uses in this Nocturne is the 4-3 on a dominant-seventh chord structures. For example, in bar 7 of theme 1a, Chopin reaches a major super-tonic chord (a secondary dominant-7th to B-major, the dominant of E) on F#. However, rather than immediately giving us this F#-major chord as a triad, Chopin holds the B from the previous E-sharp diminished-7th (a borrowed diminished-7th from F#-major: the secondary dominant we are heading to. Coincidence?! I think, not!?). The 5th degree of this chord, it becomes the 4th degree of the F# chord, before resolving to the nice juicy 3rd.

IMAGE SLIDE 6 – SUSPENSION 1

Another set of suspension examples occurs through the modulatory sequence that closes theme 1b and continues into the transition. We will look at this shortly. However, to try and avoid too much of this article focussing on theme 1, let’s look at the suspensions that feature in the second halves of theme 2.

We will be focussing on the neat melodic variation that Chopin uses on these themes shortly. However, focussing on the suspensions, we can see that theme 2a boasts two suspensions that resolve from 4 to 3 and 6 to 5 respectively, while theme 2b reduces this to one note that falls from 4-3 again, like in theme 1a.

IMAGE SLIDE 7 – SUSPENSION 2

In these two examples, we can see that there are similarities between each other and the example found in theme 1. The notes (or a note) of the previous harmony are repeated in the next chord, before resolving downwards by a step. In theme 2a, the notes are 5 and 7 of an A-major dominant 7th chord, a chord built on the flattened leading tone of B-major. These consequently become 4 and 6 of the following B-major chord before falling down a step to 3 and 5 of B-major. A nice resolution.

In theme 2b, the single held note, an E, is the root or 1 of an E-minor chord with added #4. This becomes the 4 suspension of a 4-3 downward resolution to B7.

Les Biches (RM25-6) – Francis Poulenc

How to Write Fourth Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Starting to Compose With Counterpoint: Guide to Writing Combined 1st and 2nd Species Counterpoints

How to Write Third Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write Second Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

How to Write First Species Counterpoint: A Comprehensive Guide

Making Mozart Scary

The Art of Composing for String Quartet: A Guide for Beginners

Anatomy of the Orchestra by Norman Del Mar (Book Review)

“How do I orchestrate a piece of music?” (5-tips.)

Nocturne No. 19 in E-Minor, Op. 72 No. 1 (Analysis) – Friederich Chopin

Gilderoy Lockhart – John Williams (Impromptu Melodic Analysis)

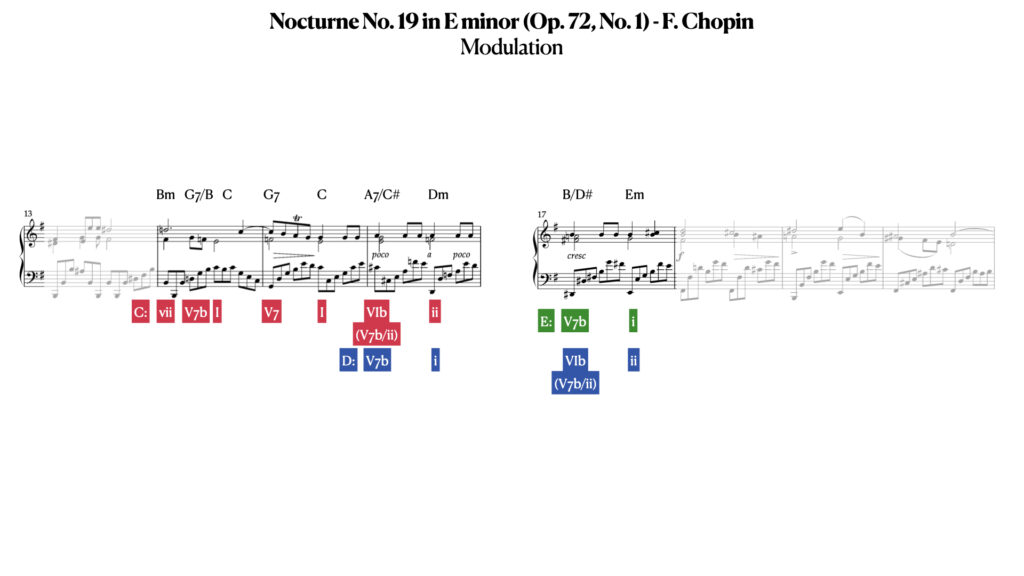

Modulation

The harmony of Nocturne No. 19 is very functional. And, despite being modest in its modulations, there are moments of great interest and formal procedures that can teach us about structural uses of harmony that could help maintain attention and expressivity. For example, the harmony that underpins Theme 1 is very grounded in its first half, while becoming much more chromatic and adventurous in its second. On a smaller scale this is structurally interesting, as Chopin gives his melody an arc. We start at home, travel to a more chromatic phase that starts in the brighter relative major, before heading back towards home. Theme 1, in other words, has a simple structural counterpoint between stable and unstable, or home and away.

Large Scale Modulations

On a larger scale, the composition does something somewhat similar to theme 1. Largely rooted in E-minor, the piece starts in the home key (E-minor, I). The piece then modulated for the exposition of theme 2, which occurs in B-major, the dominant (V) key of E-minor. The piece then moves back towards E. However, an interesting formal decision is to have the piece close using the second theme, in the parallel home key of E-major. Still using the same pitch centre, Chopin chooses the uplifting major scale to close the composition.

Chromatic Bass Line Passage

One of my favourite harmonic moments in Chopin’s Nocturne No. 19 occurs in the first repeat of theme 1(b) (bar 14-17). Like with the exposition of theme 1, the first half is rooted in E-minor. However, the second half takes us on a brief tonal adventure. Underpinned by a chromatically rising bass line where Chopin uses a set of dominant and tonic relationships outside the key of E-minor.

The first of these dominant and tonic relationships occurs in bar 14 and 15. In these bars Chopin momentarily but unquestionably establishes C-major as the tonic. And, although Chopin slightly alters the opening harmony of this part of the melody, starting on a B-minor triad, which acts as a chromatic pivot, he utilises the G-major dominant-7th structure to establish C-major in bar 14 and 15. In 14, the effect is more passing, as Chopin progresses in 1st inversion from G7 to C, which is in root position. However, in bar 15, Chopin repeats the dominant-tonic progression but with both chords in root position. The effect is more cadential and declamatory, clearly presenting C as the tonal centre.

The second pair of dominant-tonic relationships occurs immediately after this. And this is also where the chromatic bass line begins, by rolling up the typically chromatic portion of the Nocturne’s home key, E-minor. From the preceding C in bar 15, the bass line rises C#, D, D# to E.

Atop this rising bass line, Chopin builds the progression A/C#, Dm, B/D# to Em. In the context of E-minor, for example, we could label these chords Vb/VII, VII, V7b, i. Or, possibly even Vb/VII, III/V, V7b, I, if we wanted to draw out the relative major relationship of the D chord. In my more fully annotated version, where I show some of my “working”, I draw out the quality of the resolving tonics, the D and E, being the supertonic of each of the preceding tonics in the chain. In other words, D is the supertonic of C, while E is the supertonic of D.

So, that was pretty dense. What, then, do these labels and ways of looking at the progression teach us about composition? I think it shows us, particularly in the context of Chopin—or, at least, in the way we look at Chopin, who seems a very melodically driven composer—that, in fact, building from the bass is a valuable way of unlocking harmonic potential. If we were to harmonise the melody here by simply thinking about chords, I think we would deliver very different harmonic results. Instead, thinking about how a smooth bass line might work contrapuntally against the melody—assuming the melody existed first(!)—we get a novel and arguably the most harmonically adventurous moment in the Nocturne.

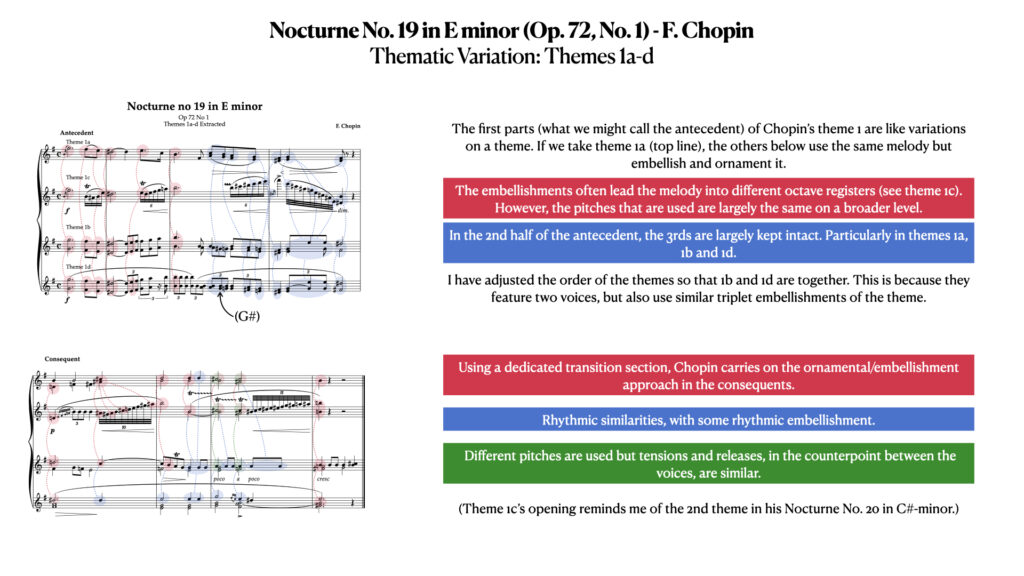

Melody and Melodic Variation

As mentioned in discussing form, there are two main melodic ideas in this piece: Theme 1 and Theme 2. Each of these themes is repeated twice more, equalling four versions of each theme (a, b, c , d). Therefore, to maintain interest, Chopin varies each theme. To do this, he primarily uses ornamentation and embellishment. However, a tactic that he also uses, which we have also seen in our analysis of Nocturne No. 20, is for him to more drastically alter the consequents of these themes.

Melody 1 Antecedent

Starting with the first melodies and, precisely, the first part—or antecedent—of these melodies, we can see how Chopin uses ornamentation and embellishment to vary the material.

Building on the same harmonic framework, which is mostly tonic and dominant chords in E-minor, the outlines are largely the same. While theme 1c does use the embellishment to switch to a higher register, it is remarkable just how all the melodies thread the same core pitches into their adventures. For example, if we take theme 1a as the theme from which the rest are derived; the other themes 1b, c and d typically end up sounding the same pitches at some point. They simply add rhythmically more dynamic ideas that diatonically and chromatically dance around the core pitches.

If we pick out bar 3 of the melodies, from the extract below—that stacks the melodies on top of one another—we can see how they all start on B. Staying on B for at least a beat all but 1c have a descending figure in 3rds in their second halves, on beats 3 and 4. Theme 1a does this in quavers, while theme 1b and d do this in triplet quavers.

Filling in the gaps created by the addition of notes that divide the beat (quaver to triplet quaver), Chopin fills in the gaps through chromatic embellishment and a change to the melodic-harmonic structure of the melody. The chromatic embellishment is simply the use of G# between A and G. However, if you recall early how we identified the use of appoggiatura in melody 1a, here the non-chord tone is changed into a passing tone form. The F# and A now fall off the beat, between two sets of notes that belong to the harmony G and B and E and G.

Of course, this language makes it more technical than I think it will have been in the act of composition. Well, at least one would imagine. However, it is surprising how diligently Chopin follows and uses what we would now refer to as part writing techniques. Sonata Secrets/Henrik Kilhamn, in covering this piece, mentions how much it reminds him of Bach’s writing. And, presumably this is what he means by it sounding more direct too. As he goes on to tell us that the piece, though published posthumously was likely written when Bach was 17. Still a student, learning his craft, is Chopin trying to calve his own style by learning from Bach? If not Bach, then it certainly feels as though it uses certain conventions, like a student might as part of an exercise. There’s a clarity of form on multiple layers.

IMAGE SLIDE: Thematic Variation: Themes 1a-d

Melody 1 Consequent

The consequents of these themes are less alike, because Chopin invites greater harmonic changes to these sections. However, there are still a great number of similarities. Each of them, for instance, become much more constrained in their spans and contours.

If we ignore the starting D-natural and octave embellishments that persist in theme 1c, many of the consequents rest on repeated notes and have spans of no greater than a fourth.

Theme 1a and 1c, which I have paired, span a minor-3rd and major-2nd respectively. Theme 1b and 1d are also constrained, spanning no more than a fourth. 1d an augmented 4th between the upper G and lower D#. 1b a perfect 4th between D and A.

In addition to this, many of them share rhythmical similarities, tensions and resolutions between the melody and harmony notes beneath.

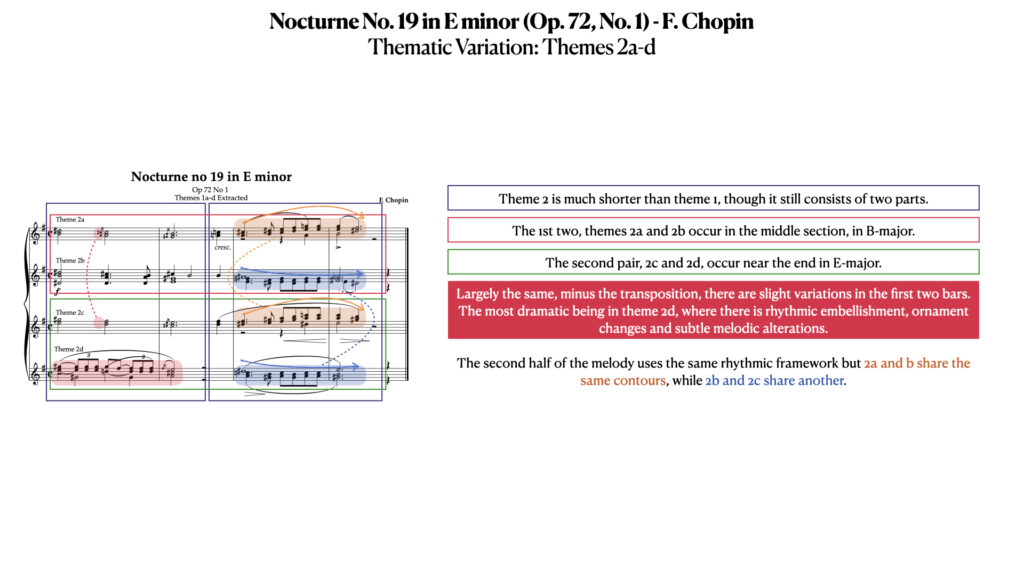

Melody 2

The 2nd melodies are much shorter than the 1s*, which itself could be seen as a point of contrast. Similar to the 1st melodies, however, these themes make use of subtle variation in their first halves. In the second two bars/the second halves of the melodies, however, there are two pairs that are nearly the same as each other. We will look at this shortly.

*The 2nd melodies are shorter, assuming you agree with my analysis. You could see 2a and b as a single 8-bar melody and 2c and d as another. I can see this too. However, my main observations here are regarding variation as opposed to thematic structure. So, whichever way you see it, hopefully you can see through the labelling.

IMAGE SLIDE: Thematic Variation: Themes 2a-d

Melody 2: transposition

Taking a step back for a moment, one large scale variation is the transposition between B-major and E-major. Themes 2a and 2b are in B-major, while Themes 2c and d are in E-major.

Melody 2: subtle embellishment in bars 1-2

The first halves of the second melodies in Chopin’s Nocturne No. 19 are much more restrained in their variation. The main difference occurs in theme 2d, which embellishes the descending idea that is used in the consequents of each melody.

Melody 2: 2-pairs (bars 3-4)

The second halves of the melody 2s are identical rhythmically. However, while one pair (2a and 2c) arc upwards, the others (2b and d) simply step back and forth before largely moving downwards a step.

The main subtle difference between these melodies is a slight harmonic embellishment on the closing harmony of melodies 2b and 2d. One boasts a suspension, while the other doesn’t.

Enough contrast, particularly with the transposition, to keep our interest, it is also highly economical writing. Chopin is able to provide us with surface level changes while maintaining structural congruity. Arguably the more taxing of compositional invention, Chopin is saving his creative energy by keeping the underlying aspects similar. Ornamentation and embellishment, be it melodic or harmonic, are easy for him to implement, even at 15 or 16.

Close

What I like about Chopin is both the indulgence and restraint that his compositions demonstrate. The beauty of the form, hanging on structural simplicity and grace. There is a clarity of form to this piece due to the economical use of similar structural components. Themes repeat with variation to the forms they take.